Initially, the inside of the historic building on Cedar Street in Austin’s expensive Hyde Park neighborhood seems ordinary: Fluorescent lights line a narrow, carpeted hallway off of which branch offices, most just big enough for a desk and a few shelves. Some share jack-and-jill bathrooms with their next door neighbors, a relic of the building’s original use.

But this structure has been altered and added onto so often that there’s a disjointed, Frankenstein’s monster-feel to some spots where former exterior walls are exposed or limestone switches to manufactured brick.

I’m there in the morning, and in the light of day, it isn’t terribly eerie. Someone brought VooDoo donuts into the reception area, so one side of the building smells like warm sugar. Everyone we pass in the narrow hallway gives a polite and knowing smile. They know why I’m here, touring the building. I’m not the first person to sniff around for ghosts.

This spot has developed a reputation for being haunted. Jeanine Plumer, who met me there, wrote a chapter on it in her 2010 book, Haunted Austin. She and her team have conducted paranormal investigations after working hours, during which they heard voices, clicks, and bells chiming. She’s been down to the former morgue, an unfinished basement area that has since been closed off. She can recite the history and lore of the building from memory. History is the key. “Ghosts love historical accuracy,” she says.

The building now houses AGE of Central Texas, a nonprofit that provides resources and services to older residents and caregivers. That’s a modern twist on the building’s original historic purpose—which was to house older women without the means to support themselves—but there is a glaring difference: It was erected as a place to serve those who served the Confederacy.

The Confederate Woman’s Home was opened in 1908 by the United Daughters of the Confederacy for older wives and widows of Confederate soldiers who couldn’t support themselves. (Confederate veterans received no federal pension—many lived in a Confederate Men’s Home across town constructed in the late 19th century.) The original two-story home for women had 15 bedrooms. After the state took over the property just a few years later, officials built a massive brick wing with 24 new bedrooms. Later, a hospital building and an annex were added. These buildings still stand today.

During its 55 years of operation, the Confederate Woman’s Home housed more than 3,000 women. As the women with direct ties to the Confederacy died off, the need for housing dwindled. In 1963, the state footed the bill to send the last three living residents to private nursing homes.

Since then, the building has changed hands and served different purposes—as a learning center used by the Texas State School for the Blind for children affected by the rubella epidemic in the 1960s, as a practice space for a local high school football team, and, since the 1980s, as a resource center for aging Texans. When AGE Central Texas turned the building into a senior center, it was the first of its kind in Central Texas.

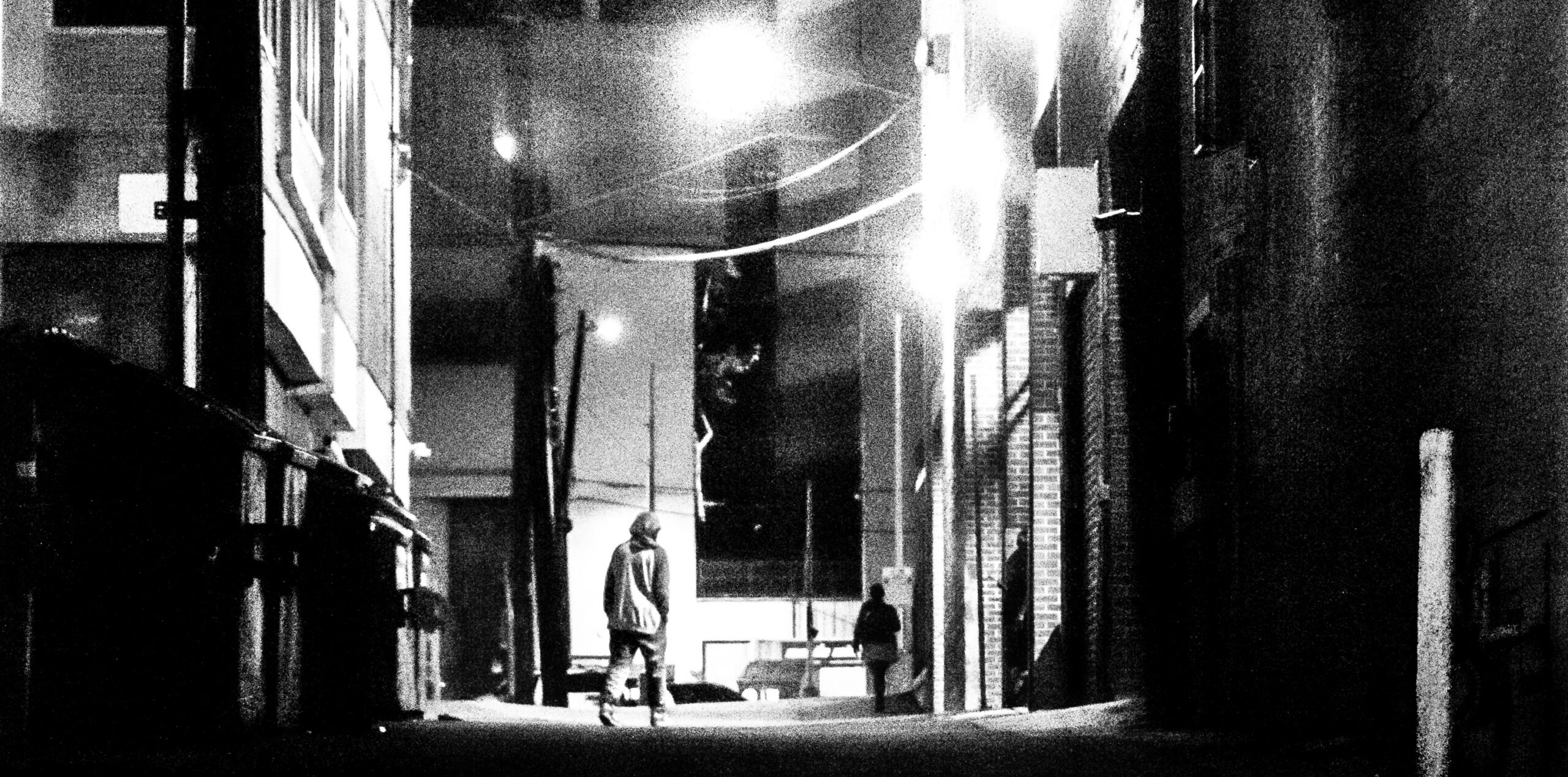

On our visit, Plumer and I walk the building’s perimeter while she tells me about her work as a paranormal expert. People call from across Texas to discuss purported paranormal experiences. The day before, she was on the phone for two hours with somebody from a retirement community in Georgetown who described seeing angels in the window of the building across the street.

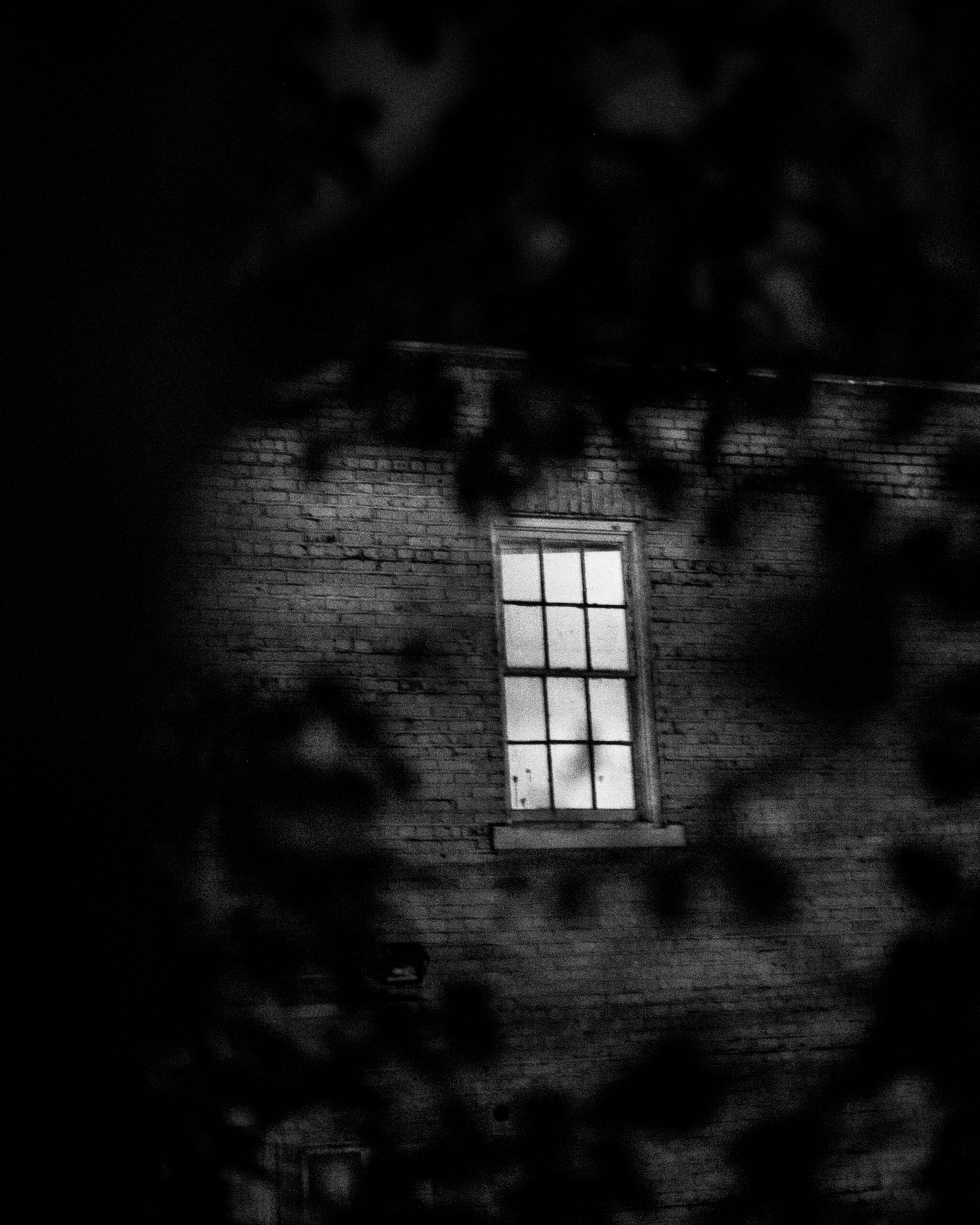

We soon arrive at dilapidated brick structures that used to house the infirmary and now hold AGE’s outdated heating and cooling systems as well as studio space rented out by local artists. Looking at the aging, boxy brick structures, I decide to risk sounding ignorant in front of a ghost expert. I tell Plumer that this space looks haunted.

“One of the reasons why buildings that are haunted tend to have this rundown look is because, when a building has a lot of that energy in it, it is off-putting,” she says. This building appears heavy because it once held people against their will, she explains, “which was probably about 50 percent of the women in the Confederate Woman’s Home.”

Inside the main building, I’m escorted by Rob Faubion, chief community engagement officer for AGE, as we peer inside offices, converted long ago from the women’s original rooms. Two large rooms bookend the side of the building that runs along Cedar Street. These were originally parlors. Faubion tells us that there are four widely accepted “entities” who seem to haunt here: two women who spend time in the former parlor, a little boy who runs up and down hallways, and a little girl who plays upstairs. The little boy once accompanied AGE’s previous chief financial officer home in order to play with her two young sons, he said. “So in the morning, she would get up and say, ‘Okay, we’re going back to the building’ and get the car,” Faubion said. The ghost, very well behaved, would listen.

Before we enter the former cafeteria, Plumer whispers that this room is particularly haunted. The large space has one exposed-brick wall, and the footprint is taken up mostly by tables and chairs. Faubian verifies the hotspot: One ghost apparently had strong opinions about seating, showing displeasure for any rearrangement by flipping chairs over in the middle of the night.

“Nothing here is malevolent,” Faubion assures us.

Today, the biggest problem for the building at 3710 Cedar St. isn’t the ghosts, but the weight of its history.

Today, the biggest problem for the building at 3710 Cedar St. isn’t the ghosts, but the weight of its history.

In front, a marker from the Texas Historical Commission declares the significance of the original building site. Beside the metal marker, erected in 2013, a larger green sign reads, “This subject marker was placed by, and belongs to, the Texas Historical Commission. It was funded by the Descendants of Confederate Veterans who have an interest in conserving Confederate History.” The sign goes on to condemn the United Daughters of the Confederacy, which is still in operation today, and whose “values are in direct conflict” with AGE’s.

In 2020, during widespread Black Lives Matter protests, AGE placed a dark plastic bag over the historical marker and requested that the Texas Historical Commission remove the marker altogether—a request the commission denied unanimously. The massive clarifying sign, it seems, is the compromise.

While the current tenants attempt to distance themselves from the building’s origins, the ghosts make it hard to forget the place’s—and Texas’—past.

I saw no ghosts here myself. But in a report adapted from a 1987 memo from a former AGE board member, two psychics who toured here said they sensed a group of women, former residents of the Confederate Woman’s Home, who are “troubled, afraid, and confused” about the changes they’ve witnessed through the last century.

“The spirits themselves are not all wise just because they are spirits,” one psychic reported. “They can have the same blindness and misunderstandings that the living have; they do not like change.”