Controversial Matagorda Bay Ship Channel Grows Closer to Reality

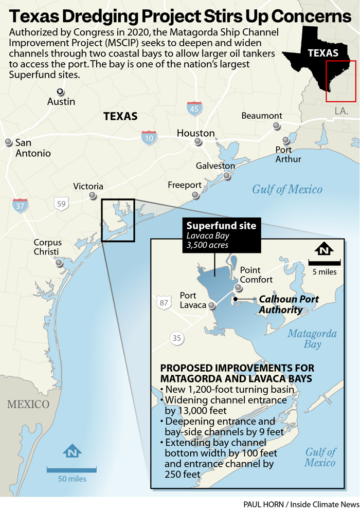

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers plans on dredging a superfund site in order to complete a massive Gulf Coast terminal for oil tankers.

This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, independent news organization that covers climate, energy and the environment. It is republished with permission. Sign up for their newsletter here.

Federal authorities have outlined a path forward for controversial plans to dredge a canal for oil tankers through a Superfund site on the Texas coast despite persistent environmental concerns.

In a presentation Tuesday night in a hotel conference room here, officials from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers outlined a $2.8 million effort to test the bay floor at the site and order the removal of any contaminants identified so that the Matagorda Bay ship channel project can move forward. The project calls for dredging and expanding a 27-mile stretch of the canal to make way for larger tankers carrying oil from Texas for export.

The corps first approved the channel project in 2020 but withdrew that decision in a court filing last December, acknowledging a need for more environmental studies. The move followed years of complaints and a lawsuit by environmental groups arguing that the corps had inadequately tested for toxic materials settled on the floor of the shallow bay.

This area of the bay, which lies midway between Galveston and Corpus Christi, was once covered in mercury, a metallic neurotoxin dumped by a now-shuttered Alcoa aluminum plant in the 1960s and ‘70s. The bay floor was designated a Superfund site in the 1990s, and a federally mandated cleanup removed most of it in the 2000s.

Tuesday’s presentation underlined the corps’s resolve to proceed with the canal’s expansion, even if tests reveal that mercury still lies on the bay floor.

“Regardless of the amount of contamination that we find, it will all be removed before dredging work commences,” said Ramon Roman-Sanchez from the corps’ regional planning and environmental center.

The $218 million canal expansion will allow the world’s largest class of ships to dock at the Seahawk Oil Terminal, owned by Max Midstream, which is partially financing the project. There, the enormous freighters will load crude oil, piped from the shale field of Texas, for sale on foreign markets.

Mauricio Blanco, a 51-year-old shrimper in Port Lavaca, expressed disappointment when he learned that the corps would be presenting plans to move forward with the project after revoking approval last year.

“I thought it was shut down for good,” he said, speaking Tuesday on his boat in Port Lavaca harbor before the meeting. “But money can buy anything, I guess.”

In the initial review of the canal project, the corps tested eight points in the 5.7 million-square-foot proposed dredging area and found no elevated mercury levels. Three more sediment samples in 2022 produced the same results.

But in its presentation Tuesday night, USACE said that a review of historical data had revealed spots of remaining contamination in or near the proposed dredging zone. In 2009, two of 23 sites tested showed mercury levels above federal limits inside the project area. Another test in 2021, just outside the project area, found mercury above twice the limit.

So, the engineers presented plans for 29 additional test sites distributed throughout the dredging zone.

Jeff Pinsky, environmental branch chief with the USACE Galveston district, said the test results should be available in about a year. Any areas of contamination will be flagged to Alcoa, which remains responsible for the Superfund site, so it can remove the toxic sediments, officials said.

The $2.8 million cost of the new testing plan will be split 75/25 between the corps and the Calhoun Port Authority, said Byron Williams, deputy district engineer for the corps’ Galveston district. The port’s director, Charles Hausmann, told the meeting that the port’s portion would be funded by Max Midstream.

Max Midstream, a Houston-based oil company, announced plans for pipelines linking the Permian and Eagle Ford shales to a terminal on Lavaca Bay September 2020 four months after the corps first approved the Matagorda canal project.

The announcement included a $360 million commitment from Max Midstream to the Port Calhoun to finance canal expansion.

Max Midstream’s Seahawk oil terminal was one of about a dozen such oil and gas export terminals proposed or in development along the Gulf Coast, all spurred by the fracking boom in Texas and the legalization of oil and gas exports in 2015.

The canal expansion has faced steep resistance from local shrimpers and oystermen as well as environmental groups. Last year, Blanco took officials from the corps and the federal Environmental Protection Agency on a tour of the project area on his shrimp boat. When the corps withdrew its approval for the project in December, he thought the battle was won.

For years, he fought the planout of concern for its effects on the bay, from stirring up old contamination to the planned destruction of oyster reefs and seagrass.

Since Blanco began working on the bay in 1989, he has seen a steep decline in shrimping productivity as industrial activity, including a sprawling Formosa plastics plant, took a toll on the coastal ecosystem. Plans to further develop the bay, he fears, may mean the end of an era for folks who depend on the natural bounty of the sea for their livelihoods.

“I’ve been doing this so long, it’s all I know,” said Blanco, a father of four, including a college student. “If I go to another job, I’ll start from the bottom.”

At the meeting on Tuesday, Blanco listened quietly. After years of speaking out against the project at similar meetings to little avail, he said he didn’t feel that it mattered what he said.

The bay floor testing results will be published in a new environmental impact study before the entire project is re-submitted to corps leadership for reconsideration and another final decision.

Despite the corps’ resolve to move forward, Col. Rhett Blackmon, commander of its Galveston District, assured the audience at the meeting Tuesday night that any new findings would undergo full administrative review before breaking ground.

“Construction will not start until the supplemental [environmental impact statement] is complete,” Blackmon said. “We won’t do anything until we get a record of decision.”

With the testing results expected in about one year, officials estimated that the new record of decision could come in 18 months.