As COVID-19 devastates workers unable to stay home, families are left struggling for justice.

By Gus Bova

January 18, 2021

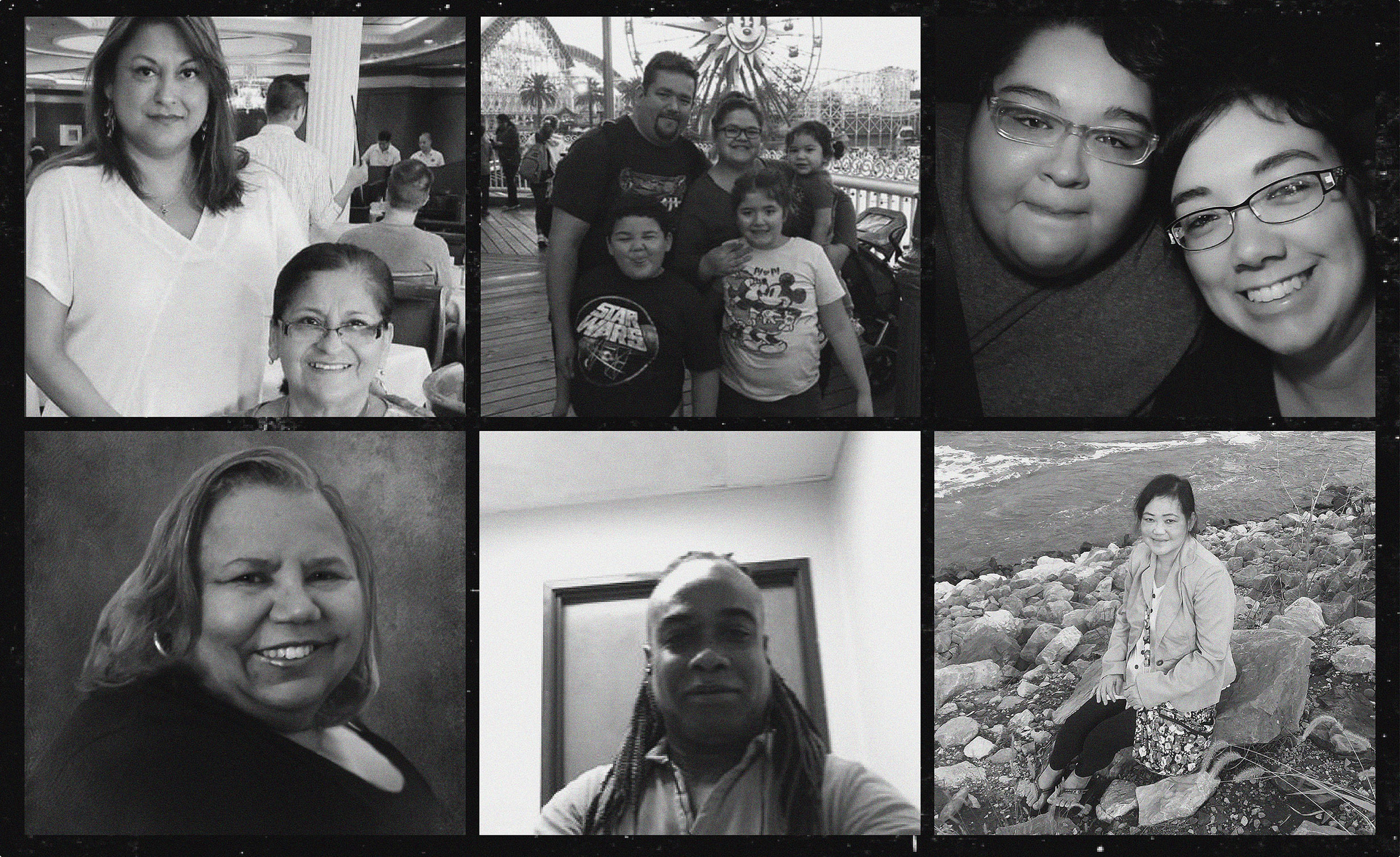

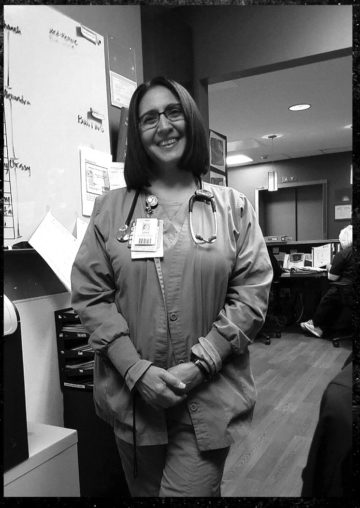

Isabelle Papadimitriou was finally a grandma. The baby girl, Lua, was born in August 2019 in Brooklyn. Though Papadimitriou lived in Coppell and worked as a respiratory therapist in Dallas, she’d been able to visit her granddaughter in New York twice, and in June 2020, she was eager to visit again. “Lua was her everything; it was all about Lua,” says Fiana Tulip, Papadimitriou’s daughter and Lua’s mother. Then, COVID-19 cases spiked in Texas and the trip no longer felt safe. They called it off, and the 64-year-old Papadimitriou started to put in extra shifts at work instead. Later that month, around the time she was supposed to be visiting family, Papadimitriou caught the coronavirus. After a weeklong struggle, she died on July 4.

A Brownsville native, Papadimitriou worked at the Baylor Scott & White Institute for Rehabilitation near downtown Dallas. According to Tulip, Papadimitriou was working with patients in the month of June without sufficient protective equipment. “As the surge hit, they didn’t have enough PPE to protect the workers, so what they did was reuse just basic surgical masks,” Tulip says, even as the rehab center was receiving COVID-positive patients from the hospital. In at least one case, Tulip says, Papadimitriou wasn’t warned that a patient she worked with had the virus. In late June, Papadimitriou began to feel sick and tried to fight the illness at home for a week. By the time she went to a hospital, her lungs were full, and it was too late. “It was so fast,” says Tulip. “It was a shock because she’s such a strong human being.”

To pay for her mom’s funeral, Tulip raised money on GoFundMe and got a grant from a foundation that gives relief to families affected by COVID-19. There are still potential ambulance and medical bills to worry about. Even though Tulip believes her mom caught COVID on the job, she can’t turn to workers’ compensation insurance, which, depending on the case, can help with medical bills, funeral costs, and lost income. As allowed by Texas law, Papadimitriou’s employer doesn’t carry workers’ comp. Tulip believes her mom’s employer failed to protect her, so she’s met with an attorney to discuss potential legal action, because she thinks the company “needs to be held accountable.”

A Baylor Scott & White spokesperson didn’t answer specific questions about the case. The spokesperson did say that “fewer than 1 percent” of employees exposed to COVID-19 patients have tested positive, and that positive tests among employees have declined over the course of the pandemic. “All staff wear masks for the duration of their shift and other PPE as appropriate,” the spokesperson noted.

Because of her daughter, Papadimitriou’s case has drawn national attention. But across the country, thousands of workers are dying from COVID-19. As of mid-January, more than 2 million Texans have gotten sick and more than 31,000 have died, many of them first responders, health care workers, prison guards, grocery clerks, and others without the luxury of staying home. Many will never be recorded, by the media or government agencies, as work-related deaths. Many grieving families will find themselves grappling with lost income, mounting bills, and no clear path to justice.

The United States, and Texas in particular, was unprepared to protect workers from COVID-19. The virus has collided with a federal and state labor safety regime that’s suffered years of malign neglect, allowing the microscopic killer to spread like wildfire through the working class. From a failure to track work-related cases to a lack of workplace safety enforcement to the maze of barriers facing families seeking compensation, it’s a situation that leaves labor advocates, like Texas AFL-CIO president Rick Levy, with a bitter taste in their mouths.

“Despite being hailed as ‘heroes,’” says Levy, “workers have basically been thrown to the wolves.”

Let’s say you want to know how many people in the U.S. are dying from COVID-19 because they had no option but to physically go to work during a pandemic.

You might turn to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), the primary federal agency tasked with promoting worker safety. The agency has a publicly available database of work-related fatality inspections, but, as late as mid-November, no COVID-19 cases appeared there. Since then, OSHA added five entries for COVID worker fatalities, with three stemming from one residential center in Florida.

You might also look to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), where you’d find a report released in July identifying 91 deaths among meat processing workers across the country and a report released in September identifying 641 deaths among health care personnel. But you’d see quickly that those CDC numbers are incomplete because not all local jurisdictions participated or submitted sufficiently detailed data.

For deaths among nursing home workers, you might turn to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, where you’d find that by December’s end, nearly 1,300 staff had died nationwide, with more than 100 in Texas. But that reporting only began in May, and there are some data-quality issues. For Texas, the state health department’s COVID-19 dashboard will do you no good either, although you can go over to the state prison system’s website to see the names of corrections officers who’ve passed.

The virus has collided with a federal and state labor safety regime that’s suffered years of malign neglect.

Usually, the most reliable count of work-related fatalities comes from a yearly census by the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), which draws on a dizzying array of governmental and nongovernmental data sources. But, in an email, a BLS spokesperson said the agency “will not specifically compile COVID deaths and publish estimates.”

In a bid to fill the gap, unions, nonprofits, and media outlets are publishing their own data. The United Food and Commercial Workers said in December that 350 of its members had died of COVID-19. As of mid-January, Kaiser Health News and the Guardian had identified more than 3,000 lost health care workers, and the Food and Environment Reporting Network had identified more than 350 deaths among meat processing and agricultural workers. But all are incomplete counts, a photograph encountered in small shreds, and they generally don’t distinguish with confidence whether a COVID-19 case was contracted at work or not.

Given the nature of the virus—which takes days to manifest symptoms and can spread without a person feeling sick—tracking work-related deaths was bound to be a herculean task. Still, advocates say, the lack of a unified national or state effort to do so amounts to one more public health failure, and one more break in the chain of accountability.

From the early days of the pandemic, advocates saw the threat COVID-19 posed to workers. The main demand from labor advocates was for OSHA to issue an emergency temporary standard—an enforceable set of rules requiring employers to take measures to protect employees from the coronavirus. In early March, the national AFL-CIO petitioned OSHA for such a standard, but the agency denied the request. The union sued the agency to compel it to issue new rules but was rebuffed by an appellate court in June. Instead of enacting a new standard, OSHA has relied on mostly unenforceable advisory guidance and, in the rare cases it has punished an employer, existing rules about protective equipment or paperwork that aren’t tailored to a pandemic like COVID-19. Under President Trump, the number of federal OSHA inspectors also dropped to its lowest level in 45 years.

Employee and employer advocates note there was very little safety guidance until April, and OSHA’s subsequent advice has sometimes contradicted itself more quickly than affected parties can get a grasp on it. For example, guidance in April suggested that most employers needn’t worry about recording or reporting COVID-19 cases. In May, the agency walked that back, saying most employers are potentially required to record and report, but still leaving significant ambiguity and discretion to employers.

“It is a complete and total failure; it’s a stunning failure,” says Debbie Berkowitz, a former OSHA policy adviser during the Obama administration and now the worker safety and health program director for the pro-worker National Employment Law Project. “OSHA is a failed agency in every way.”

Things could have gone differently. During the 2009 “swine flu” pandemic, Berkowitz says OSHA provided clearer expectations to employers than it has today. But the agency also realized it needed a permanent standard for airborne infectious diseases and began the laborious process of federal rule-making. In 2017, the airborne infectious diseases standard was on the verge of implementation when the Trump administration spiked it in the name of cutting bureaucratic bloat. Those rules would have compelled the health care sector to prepare for a pandemic like COVID-19, including stockpiling respirators, and the requirements could have been expanded to other industries.

Berkowitz also condemns Trump’s late-April decision to issue, at the behest of industry lobbyists, an executive order aimed at stopping local public authorities from closing meat processing plants. “It wasn’t just that there would be no standard, but they went farther to aid and abet industries in sacrificing essential workers’ safety and health,” she says. Texas has seen more than 1,900 COVID-19 cases tied to meatpacking facilities, particularly in the Panhandle and East Texas.

Some states have stepped into the breach. About half run their own OSHA-approved occupational health and safety programs, known as “state plans,” rather than relying on the feds. California has had its own airborne disease standard for the health care sector since 2009, while some states, including Virginia and Michigan, have now issued their own temporary emergency standards, like those demanded by the AFL-CIO. But Texas—the country’s second-most-populous state and the first to pass 1 million confirmed COVID-19 cases—has no such state program and has taken no similar action.

Employer and industry associations lobbied against a nationwide COVID-19 standard, fearing over-regulation and financial sanctions. But a state-by state patchwork, along with shifting federal guidance, has caused its own problems. “Most of the employers I’m working with that have operations in multiple states would actually prefer to have a single standard to work with,” says Cressinda Schlag, an Austin attorney and blogger who works at a law firm that represents employers. “Employers have had a huge struggle this year: In addition to OSHA guidelines, there’s CDC guidance, there’s state and local orders and requirements … there’s a lot of inconsistencies.”

As for enforcement, OSHA began issuing press releases in early October announcing COVID-related citations. These releases do not include the state-run programs. The earliest penalties were issued in July, but most were in September or later. Since there’s no emergency standard, they’re primarily for violations of existing safety standards, or, starting in September, some failures to record or report COVID-19 cases and deaths. As of December 31, there were 301 citations, the majority from worksites in New York and New Jersey, which have seen disastrous nursing home outbreaks and where health care worker unions have actively pushed complaints. Seventeen of the citations were in Texas. For comparison, federal OSHA received around 14,000 COVID-related complaints last year.

The fines were small, even for worksites where multiple employees died. The highest was $33,000, with most being half that or less. The seventeen Texas citations amounted to $145,000.

“It’s not even a slap on the wrist,” Berkowitz says, referring in particular to a $13,000 fine issued to a South Dakota meatpacking plant. “It’s a signal to the whole industry: Don’t worry; there aren’t real consequences.”

Yolanda Reyes, 66, and Casandra Gonzalez, 50, were friends as much as they were mother and daughter. They lived together in a house in Cypress, splitting the mortgage and utilities; they took cruises together. Eleven years ago, Reyes even donated a kidney to Gonzalez. In May, as Gonzalez was going to her customer service job, Reyes was worried: Gonzalez’s immune system had been weak since the transplant. Sure enough, in mid-June, two co-workers Gonzalez sat close to tested positive for COVID-19, Reyes says. On June 24, Gonzalez tested positive herself.

Reyes isn’t a nurse or a doctor, but she knows about sanitation through her cleaning jobs. She quarantined her daughter in a room of the house and donned a face shield, gown, and gloves to bring her food and tend to her. She disinfected everything. Gonzalez didn’t want to go to the hospital, so Reyes simply did what she could. But things went south suddenly, and on July 1, when Reyes went to rouse Gonzalez, she saw her daughter’s lips were turning blue. The ambulance came and took Gonzalez to the hospital, where she passed on July 4.

“My heart is gone, because she’s gone,” Reyes said as she choked back tears during a November phone call. “Think about it: I was 16 when I had her. We were friends. We were good buddies; we were traveling buddies. She would go to the store and say, ‘Here, Mama, I brought you a blouse. I think this would look good on you.’ She would color my hair because she didn’t want me to look old.”

After Gonzalez’s death, the bills came: around $4,000 for the cremation and $2,700 for the ambulance, says Reyes, with more medical bills likely to come. On August 3, Texas Mutual Insurance denied Reyes’ workers’ comp claim, saying her daughter’s illness wasn’t work-related. Over the past two years, Texas Mutual has twice had enough money on hand to pay out $330 million in dividends to policyholders.

Reyes is far from alone. According to data provided by the Texas Department of Insurance (TDI), the state agency that oversees the workers’ comp system, insurance carriers reported about 36,000 COVID-19 claims last year. As of December 31, 62 percent had been denied. Of 139 claims in which the worker died, 93 had been denied.

The data show discrepancies by occupation: Firefighters were denied about a quarter of the time, while police and hospital employees were denied around a third of the time; prison employees, food and drink service workers, and school staff all saw denial rates above 80 percent; grocery workers were denied 97 percent of the time. TDI cautions that these data include “exposure-only” claims, in which a worker did not submit proof of a positive COVID-19 test or diagnosis; the agency is working to separate out those claims and has so far found that, through September, about half of claims including a positive test had been accepted.

In workers’ comp claims where the employee died, a family could ultimately receive payment of medical expenses and wage replacement, plus death and burial benefits. To prevail, they don’t have to prove the employer was negligent, just that the person most likely got COVID-19 while doing their job. Nevertheless, insurance carriers are incentivized to deny claims to avoid paying the money, and employers are incentivized to assist in those denials so that their premiums don’t go up. Insurers can deny for multiple reasons, but the go-to move is to claim the illness wasn’t work-related.

Governors in around a dozen other states, including Illinois and Kentucky, foresaw this problem and either signed bills or took executive action to create a legal presumption that COVID-19 cases among essential workers are work-related. Texas Governor Greg Abbott has taken no comparable action.

“My heart is gone, because she’s gone.”

Michael Sprain, a Houston attorney who fights workers’ comp denials, says his firm has been contacted by hundreds of people with COVID-19 claims. In his experience, the only workers getting regularly approved are “first responders,” meaning cops, firefighters, and EMTs. This makes sense, since Texas law already contains a work-relatedness presumption for first responders for diseases “of the lungs or respiratory tract.” But even that’s been a fight: In April, Sprain helped the local firefighters union push Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner to stop denials of firefighters’ COVID claims.

Sprain has taken on dozens of non-first responder cases—including Reyes’—in which a worker either passed away or suffered long-term health damage. Sprain believes he can get the denials overturned, but it may be slow going. After the initial denial, there’s a review conference with the insurance carrier, then potentially an administrative hearing, and later a state appeals panel. Only at that last stage could a decision become precedent, but no COVID-19 claim has gotten there yet.

Even as families struggle with the workers’ comp system, there’s another wrinkle for Lone Star State employees: Texas is the only state in the U.S. that lets most private sector employers opt out altogether. Roughly 30 percent of employers here don’t carry workers’ compensation insurance.

Generally, lacking workers’ comp is a bad thing for working families, but it’s a sword that cuts both ways. The century-old bargain enshrined in workers’ comp is that bosses foot the bill for an insurance policy that pays out in case of injury or death on the job, and, in return, employees and families forfeit their right to sue the employer (except in extreme cases). Texas employers who opt out, therefore, are vulnerable to lawsuits.

That’s why Fiana Tulip might have a viable path to sue over her mother’s death. If she does, she would join a small group of plaintiffs trying to chart somewhat novel legal territory. A Virginia-based law firm is maintaining a database of COVID-19 related lawsuits, and just a handful of suits in Texas over work-related COVID deaths appear as of January. None have gone to trial.

Quentin Brogdon, a Dallas attorney and board member of the Texas Trial Lawyers Association, is the attorney on one such case. He’s representing the family of Maurice Dotson, a 51-year-old nursing assistant who died in Austin in April. Roughly put, Brogdon will have to prove it’s more likely than not that Dotson caught COVID-19 at work and that the employer was at least somewhat negligent.

In such cases, a sympathetic jury could feasibly award damages of hundreds of thousands or even millions of dollars. But Brogdon says there’s no need for employers to worry about a flood of lawsuits, noting that he himself has been turning potential clients away. “I have been called by many other lawyers and random clients who sought me out on the internet and I’ve said no to all of them,” he says. “Because these cases are so hard; they’re so difficult.”

Regardless, business lobbyists have spent months pushing for legislation to shield employers from COVID-related lawsuits. Texas’ senior U.S. Senator, John Cornyn, filed a bill in July that would likely quash most COVID-19 suits and even apply retroactively, though the legislation sputtered due to the resistance of Congressional Democrats. Some states, including Kansas and North Carolina, have already passed similar laws. Top state officials in Texas have voiced support for a liability shield, making it likely to come up in this year’s legislative session.

On the other side, Texas labor leaders will be fighting for legislation that creates a presumption of work-relatedness to patch up the workers’ comp system. As of January, a number of bills have been filed covering different combinations of first responders, corrections officers, school employees, and nurses. The Combined Law Enforcement Association of Texas (CLEAT), the state’s largest police union, is also pushing for legislation ensuring that the families of certain public employees receive a special death benefit administered through the state retirement system.

At the federal level, worker advocates hope a Biden administration will soon be rebuilding the U.S. worker safety system. In his platform, the president-elect expresses support for the emergency temporary standard that unions have called for and for finalizing the permanent standard that was scrapped in 2017. “It’s going to be a huge lift because OSHA’s been gutted, but I am hopeful,” Berkowitz says.

“I do believe in my heart that my mom was a hero,” says Fiana Tulip. “But I don’t believe that she wanted to be a hero.”

Since her mom passed, Tulip has emerged as a voice for those who’ve lost family members to the coronavirus. In July, a friend told her about a group called Marked by COVID, which is helping relatives publish obituaries that call out elected leaders for their failures to address the pandemic. Tulip wrote an obituary and an op-ed in the Austin American-Statesman, inviting Governor Abbott to her mom’s funeral in July. After that, it was “just full speed ahead,” Tulip says, as a swarm of media outlets began contacting her. She also set up a group called I Lost My Loved One(s) to COVID on Facebook.

By connecting with others in her situation, Tulip found a community to help her cope with her loss. Still, she’d rather just have her mom, and she’s convinced things didn’t have to go like this.

“Her place of work, which she trusted, didn’t protect her and didn’t honor her life the way she deserved,” Tulip said during a November Zoom call, shortly after cajoling her 1-year-old, Lua, into taking a nap. “Our leadership, our president … has just failed.”