5 Texas Criminal Justice Stories to Watch in 2020

“Progressive” prosecutors, bail reforms, and increased calls for accountability will all likely be in the news next year.

At the state level, 2019 was largely a year of missed opportunities for reforming the criminal legal system in Texas. Despite a reputation for leading on criminal justice reform, Texas lawmakers accomplished very little in this year’s legislative session. Yes, they mandated some baseline protections for women behind bars. And they killed the Driver Responsibility Program, a much-maligned surcharge system that prevented more than 1 million Texas drivers from keeping or renewing their licenses, which some lawmakers had wanted to eliminate for years. But beyond that, as Scott Henson—a widely recognized criminal justice researcher who writes the must-read blog Grits for Breakfast—put it, the 86th session was a “killing field” for criminal justice reforms.

While the Legislature won’t meet again until January 2021, there are still developments at the local level that could lead to significant changes in the coming year. Here are a few I’m watching:

What’s a “Progressive Prosecutor”?

Houston-area progressives supported Kim Ogg when she first ran for Harris County district attorney in 2014. At the time, she signaled a departure from the tough-on-crime, lock ‘em up-mentality that once reigned in Texas’ largest city, instead vowing to reform how prosecutors handle petty pot cases. She lost that election, but succeeded in 2016 after running on a similar, reform-minded platform. After her election, she implemented diversion programs for misdemeanor marijuana possession and other low-level offenses, and declared herself “part of the national reform movement,” which in recent years has started to focus on electing progressive prosecutors committed to dismantling mass incarceration.

That movement has grown beyond Ogg and the low-hanging fruit improvements that defined her first two campaigns. In the years since, it has favored DAs who have promised to make more fundamental changes, like refusing to prosecute certain drug cases, reforming probation, and changing how crimes related to poverty and homelessness are handled. In the meantime, Ogg has back-tracked on issues she once vocally supported, like bail reform, and has repeatedly tried to expand the DA’s office, further souring her reputation among reformers.

Ogg now faces multiple challengers from the left in the March 2020 Democratic primary, as do misdemeanor and felony prosecutors in two other must-watch primaries in Travis County. How these races shake out, and what policies the victors ultimately push, could redefine what it means to be a progressive prosecutor in Texas.

Help Not Handcuffs

Last year, the Dallas Police Department created a special team comprised of an officer, paramedic, and social worker to patrol South Central Dallas, an area with a high concentration of mental health-related police calls. That pilot program, aimed at putting people in treatment rather than jail, appears to be working enough for Dallas to try expanding the program citywide.

More Texas cities seem to be embracing the approach. Earlier this year, the Austin City Council approved an additional $1.7 million in funding for paramedics and clinicians to help field 911 calls and divert mental health crises to caseworkers and EMS rather than police.

Bail Reform, Redux

In more Harris County news, this year officials settled a landmark lawsuit over bail policies that keep low-level defendants in jail because they’re poor, ushering in reforms that were largely made possible thanks to a Democratic sweep in the 2018 midterms.

Although that settlement established sweeping new protections, reformers see their victory in Harris County as just the first step. The same legal team that successfully reformed the county’s misdemeanor bail policies filed a second lawsuit challenging how judges decide bail at the felony level. Similar lawsuits have been filed in Dallas and Galveston counties too.

If we’ve learned anything, next year should provide even more examples of the need for oversight of TDCJ before state lawmakers reconvene in 2021.

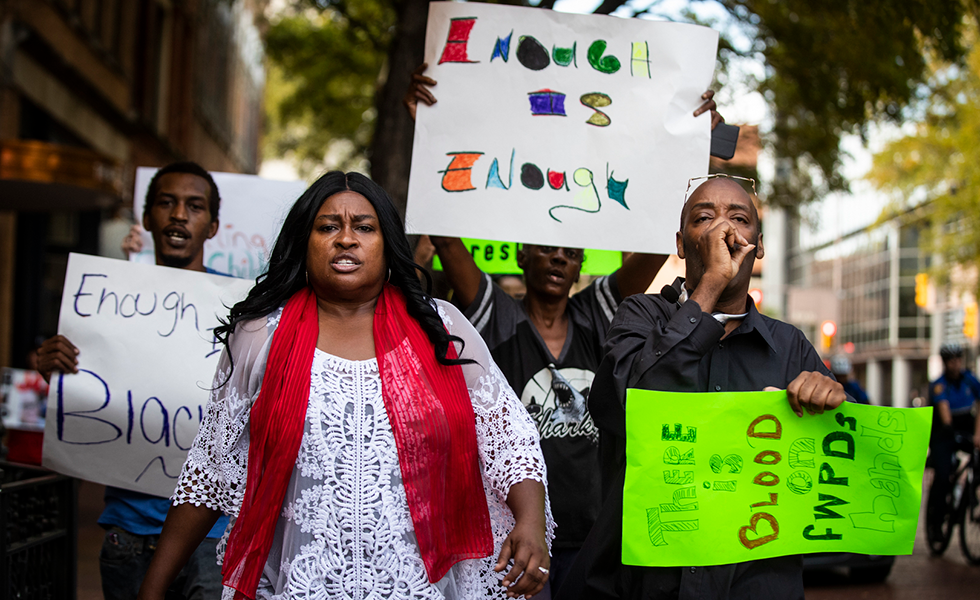

Policing the Police

The Black Lives Matter movement and the renewed focus on police violence has put a spotlight on the way police departments investigate themselves. Tragedy can jumpstart the discussion, as we saw this year with the case of Botham Jean, an unarmed black man shot to death inside his own apartment by a white Dallas police officer. This year, the fallout from Jean’s death led to new calls for police accountability and expanded community oversight for the Dallas Police Department. Officials in neighboring Fort Worth are also pursuing a plan for civilian police oversight. The impetus: the death of Atatiana Jefferson, a black woman shot to death by a white officer dispatched to her home for a routine welfare check in October.

Crisis of Confidence at the Texas Department of Criminal Justice

There have been at least 24 heat-related deaths inside Texas’ uncooled prisons over the past two decades. After fighting a lawsuit over the issue for four years, the Texas prison system was finally forced into a settlement last year that mandated air conditioning for medically vulnerable inmates—an agreement prison officials kept getting dragged back into court for breaking this year. As 2019 ends, Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) officials stand accused of lying to cover up prison temperatures and face threats of jail time from the very frustrated federal judge on the case.

Advocates for prison reform have asked lawmakers to create an independent body to monitor TDCJ thanks to the steady drumbeat of scandals at the agency—from heat deaths to guards planting contraband on prisoners to rising reports of suicide and use of force behind bars. This year advocates renewed their push to create a watchdog office that would inspect and report on problems inside the state’s adult lockups (which is what lawmakers created for Texas’ scandal-plagued juvenile prisons more than a decade ago). The bill stalled, but if we’ve learned anything from this year, the next one should provide even more examples of the need for oversight before state lawmakers reconvene in 2021.

Read more from the Observer:

-

Where the Bodies are Buried: In 1910, East Texas saw one of America’s deadliest post-Reconstruction racial purges. One survivor’s descendants have waged an uphill battle for generations to unearth that violent past.

-

Why I Started a Book Club in the Harris County Jail: Education programs make jails safer and reduce rates of recidivism when people reenter society.

-

Texas’ Method for Funding Courts is a Colossal Waste of Time and Money: Criminal fines and fees, in addition to trapping poor people in a cycle of debt and incarceration, are an incredibly costly source of revenue for local governments, according to a new report.