Dallas Isn’t Ready to Remove its Confederate Monuments

Citing costs, Dallas’ mayor and eight other Council members voted to delay the removal of the Confederate War Memorial across from City Hall.

On March 3, 1910, Allen Brooks, a 65-year-old black laborer, was beaten, stabbed and dragged through the streets of downtown Dallas. As Brooks, who denied accusations that he raped his employer’s daughter, prepared to stand trial, an angry mob burst into the courtroom, tied a rope around Brooks and threw him out a second-story window.

Cheers erupted from the crowd of 5,000 people who’d gathered to witness the lynching. The mob used the rope to drag him through the city streets and hang his mangled body from a telephone pole, blocks away from Dallas’ 60-foot Confederate War Memorial that had been erected a decade earlier. That monument — along with four others built during Jim Crow — has been the target of activists in recent years.

But on Wednesday, after months of deliberation, the Dallas City Council voted 9-6 to delay a decision on whether to remove the 60-foot monument, which is now on the lawn of the Kay Bailey Hutchison Convention Center across from City Hall. Instead, the council voted to create a memorial to Brooks’ lynching — an attempt at a compromise that doesn’t sit well with many in Dallas.

“Creating additional monuments that acknowledge some of the victims of the acts of those who prescribe to the racist ideologies is not going to mitigate the negative effects of their existence,” Aubrey Hooper, president of Dallas’ NAACP chapter, told the Observer.

Mayor Mike Rawlings and Mayor Pro Tem Dwaine Caraway cited cost concerns as their reason for punting on a decision. Caraway and Rawlings cast two of the nine votes against another provision to auction the Robert E. Lee statue, valued at $1 million, that was removed from Dallas’ Oak Lawn Park in September. Proceeds would have gone toward the costs of taking down the war memorial.

“Cost-wise, do you spend $500,000 and take down the whole statue and destroy it, or do you try to add history that’s not been told?” Caraway told the Dallas Observer, suggesting the figure of the Confederate soldier atop the memorial be replaced with Martin Luther King, Jr.

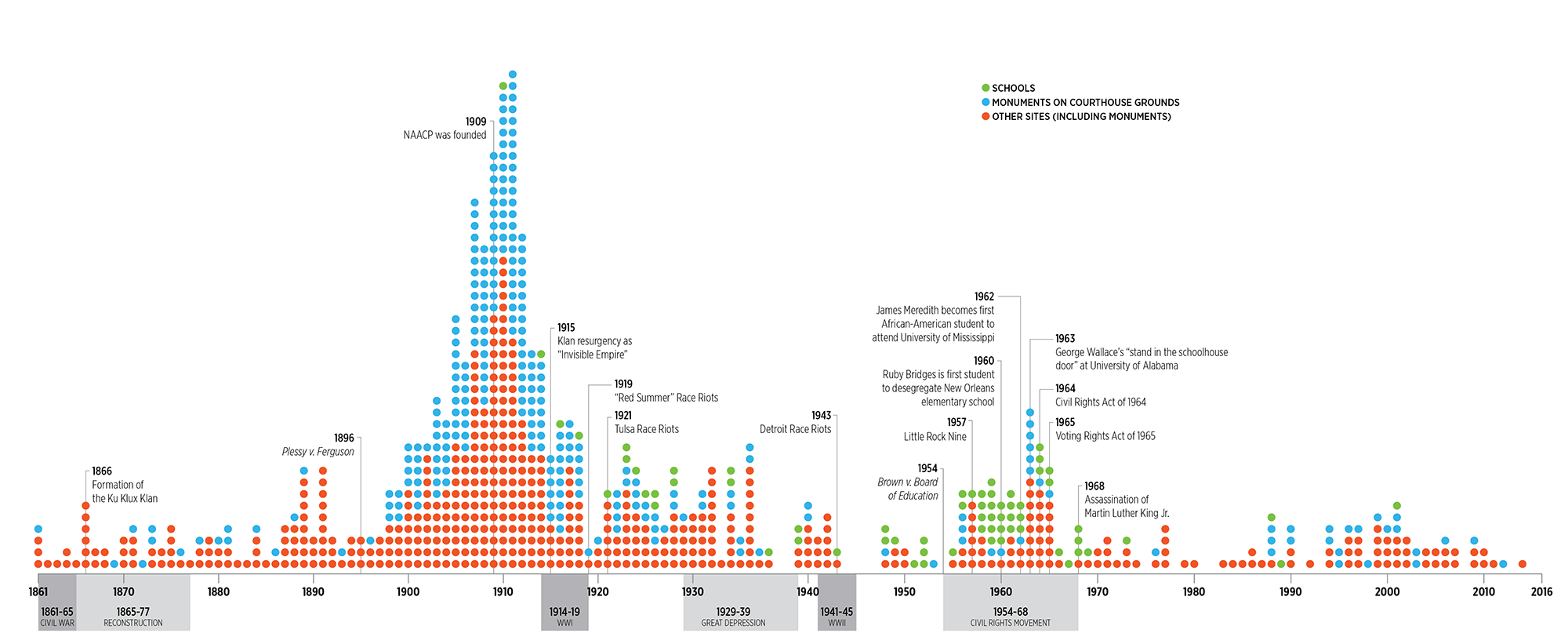

Of Texas’ more than 170 Confederate memorials, many were put up amid spasms of racial violence in the first two decades of the 20th century and again during the civil rights movement. The statues were intended to intimidate black Americans and celebrate a revisionist history of the Civil War. Nearly 500 lynchings took place in Texas from 1882 to 1968.

“Public monuments to the Confederacy and its leaders serve only to distort the truth about the nature of slavery and the Civil War itself,” said state Representative Eric Johnson, D-Dallas, who’s called for a Confederate plaque inside the Capitol to be removed. “I find both slavery and its apologists odious and entirely unworthy of honor in any of our public spaces which are maintained with taxpayer funds.”

Michael Phillips, a historian who researches race relations in Dallas, said the decline in media attention on symbols of the Confederacy has given the City Council the space to kick the can down the road. Phillips said he believes the council’s reluctance to remove monuments, rename streets and landmarks and implement racial equity projects stems from their loyalty to a “white donor base.”

“There’s a conservative old guard that still runs Dallas that’s still fond of those monuments,” Phillips told the Observer.

Many of the supporters in attendance at the Wednesday council meeting were members of This Is Texas Freedom Force, a rifle-wielding group that has advocated to keep monuments in other cities, including Houston and San Antonio. One supporter likened the proposal to “when the Nazis took over” and destroyed statues they didn’t like. After the vote, an opponent was booted from the council meeting, yelling “Shame on you.”

It’s unclear when the city will take up the issue of the war memorial again, though the council on Wednesday voted to create a “working group to recommend the scope for adding a full historical context.”

“They [Dallas City Council] simply want to have this circus again before they actually vote to remove it,” said Council member Philip Kingston, who led the charge to take down the memorial. “It might be easier if we just die of embarrassment.”