Maria Campos wasn’t going to wait till the dam behind her house burst and washed away her home and her family. It was August 26, 2017, a Saturday, and Hurricane Harvey had parked itself over southeast Texas, unleashing biblical amounts of rain. Ivanhoe, where Campos lives, is a tiny town of 1,800 people 100 miles northeast of Houston, and it saw 27 inches in just five days. About 200 feet from Campos’ backyard, Lake Ivanhoe began rapidly filling behind its earthen dam. The front yard had already flooded, washing away her carefully arranged potted plants.

“The water is coming up, up and up,” she recalled. “My husband say, ‘This is serious, because the lake is already full.’ You can see the little fish in my yard. It was like a river.”

Though Lake Ivanhoe dam isn’t huge — about 19 feet tall and 590 feet long — it holds back about 34 million gallons, or enough to fill 50 Olympic-size swimming pools. Not willing to take the chance that the dam would burst and flood her home, Campos and her husband piled their teenage daughter, Karen, and dog, Spicy, into their gray Kia Sportage and settled in with a neighbor on higher ground down the street.

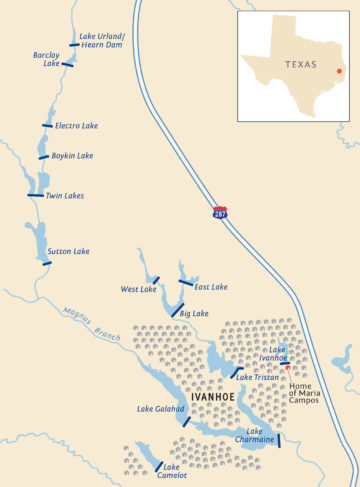

The Camposes weren’t the only ones in trouble. By August 28, three days after Harvey made landfall, lake levels at 14 dams in the Ivanhoe area were rising dramatically. Within Ivanhoe city limits, all five lakes were full and water was rushing over the top of four dams, putting enormous stress on the earthen embankments. If the dams failed, 400 million gallons of water would be unleashed on the town and downstream areas. And because many of the area’s roads run across the embankments, rescuing people stranded in their homes would suddenly become much more difficult.

Officials in Ivanhoe began to panic. Of particular concern were the eight reservoirs on Magnus Branch, a creek that runs through Ivanhoe. At Lake Urland, the reservoir farthest upstream, water rushed over the emergency spillway, digging out a 15-foot-long rut. If the spillway eroded too quickly, it would unleash a wall of water from the lake. As the torrent surged down Magnus Branch, it damaged Electro Lake dam. City officials worried that if the dams on Electro Lake or Lake Urland fully collapsed, a surge of water could topple the five downstream dams in succession, like a row of dominoes. If that happened, dozens of lakefront properties would be flooded in Ivanhoe.

“I was calling my neighbors, telling them we might have a wall of water in half an hour,” said Catherine Bennett, the mayor of Ivanhoe.

It wasn’t a far-fetched scenario. After all, it had happened once before. In 1996, the Magnus Branch watershed got 16 inches of rain in 24 hours. Ten of the 14 dams in the area failed. On Magnus Branch, five dams crumbled, sending millions of gallons down to Lake Galahad, which then overtopped and breached, leaving a 40-foot-wide hole at the base of the dam. The water eventually ripped through Lake Charmaine dam, creating a 100-foot-wide gash in the middle, uprooting trees and emptying the lake. Many lakefront homes in Ivanhoe flooded.

Bennett was aware that history could repeat itself. Though the dam on Lake Charmaine had been rebuilt in 2003 and reinforced with concrete, it still had major problems. Every couple years the city’s dam supervisor kept discovering voids big enough to fit dozens of dumpsters. Seepage on the downstream side of the dam had alarmed state regulators with the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ), who ordered the city to take action. The city filled the voids and caulked cracks, but it didn’t have enough money to do everything TCEQ asked.

By Thursday, August 31, six days after Harvey’s landfall, floodwaters had crept into two of the Campos’ bedrooms. A spillway pipe in the Ivanhoe dam — the one behind Campos’ house — also gave way. Luckily, the four other dams in town held. Perhaps it was because they had been regularly maintained and upgraded, or because the rain eventually let up, or sheer luck.

Dams all across East Texas failed that week. On Tuesday, August 29, in Sam Houston National Forest, the rain washed away 11 feet on one end of Spring Lake dam, an earthen embankment that holds back a 14-acre lake. That same day, further east in Polk County, a sinkhole five feet deep and 11 feet wide opened up in the middle of Lake Mark dam, and Armadillo Drive Lake dam overtopped. By the end of the week, water had punched through Forest Lake dam in Tyler County, collapsing a 30-foot section and emptying out the lake.

In total, 20 dams across Texas overtopped, breached or suffered damage during Harvey that the state considered a “failure.” All were under 45 feet tall, and most were classified as “small” by the state. Eleven of the 20 are exempt from state regulations, thanks to a 2011 law that allows the owners of small dams to police themselves.

Hurricane Harvey focused attention on Houston’s Addicks and Barker reservoirs, where developers had built homes and sold them to unwitting buyers. Much less scrutiny has been brought to bear on small dams, even though an Observer investigation found that the vast majority of failures in Texas involve dams that impound less than 1,000 acre-feet. Despite their size, many small dams are ticking time bombs, according to safety experts. Big dams are usually owned by government agencies such as river authorities, which have money for upgrades and are regulated by TCEQ. Small dams are typically owned by individuals, homeowners associations and cash-strapped counties that can’t afford expensive improvements. In the Ivanhoe area, for example, four of the 14 dams are owned by the city, while the remainder are controlled by a property owners association, a Boy Scouts council and private landowners. Many are decades old, built at a time when flooding wasn’t as severe and not as many people lived downstream.

The failure of small dams has the capacity to cause real harm. A federal study found that of the 300 fatalities that occurred nationally as a result of dam failures between 1960 and 1998, more than 85 percent were caused by dams less than 50 feet in height. In Texas, almost half of all dams are considered too small to regulate and are exempt from inspections and oversight.

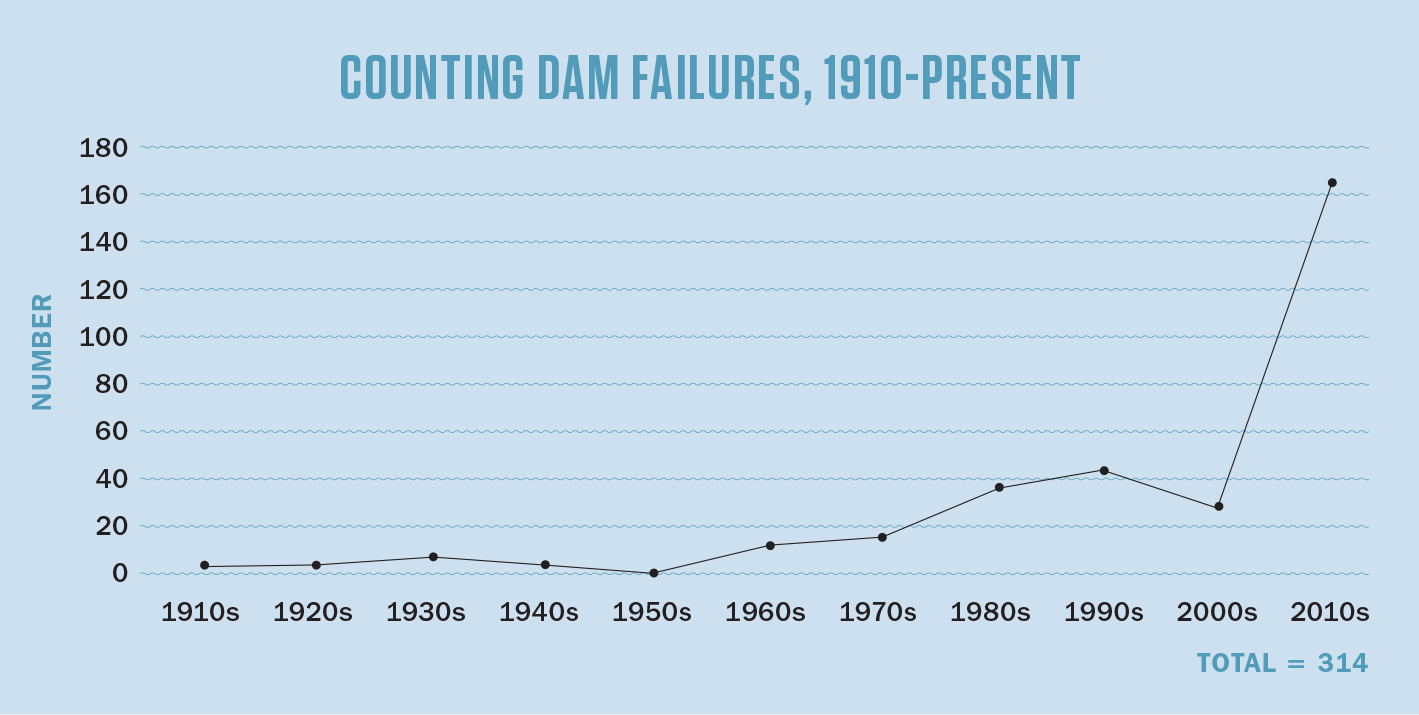

The Observer’s review of 7,250 dams under the state’s purview found that more than 25 percent of those regulated by TCEQ are in “poor” or “fair” condition, the two lowest ratings. Perhaps most important, state data also show the rate of failure is increasing dramatically. Of the approximately 300 dam failures in Texas since 1910, half have occurred in the last nine years. About a third of the failures were a result of overtopping, when water rushes over the top of a dam that’s not designed to function in such severe conditions. Overtopping can damage the structure and put it at greater risk of collapse.

“The problem is the smaller dams,” said Wes Birdwell, a civil engineer in Austin. Many of them were built several decades ago, Birdwell said, and predate TCEQ’s dam safety program. “There’s more that’s going to fail,” he said. “Maybe somebody’s grandpa bought a bulldozer … and scraped up a bunch of dirt. We don’t know a lot about a lot of these dams.”

TCEQ spokesperson Andrea Morrow said that the agency makes recommendations, but “it is the responsibility of dam owners to address those recommendations.” She pointed out that approximately 100 of the 300 dam failures were breaches; the remaining 200 were related to problems with minor overtopping, spillway damage and other non-catastrophic problems.

Morrow also said smaller dams may be failing because of their age. “Many of the small dams in Texas were built more than 40 years ago without engineering design or supervision, or even state regulation,” she said. “The age of a dam can be a contributing factor in a failure, especially if an owner does not have the necessary funds to repair or rehabilitate the dam.”

In many ways, the agency’s efforts are hamstrung by the Legislature. Lawmakers removed almost half of all Texas dams from state oversight in 2011. The budget for TCEQ’s dam safety division is $2.6 million, and the department employs just 25 inspectors — that’s one inspector per 158 dams. As a result, almost a fifth of the state’s high- and significant-hazard dams are overdue for inspections. Morrow said that “weather, disaster events [and] inspection schedule conflicts with dam owners” contribute to delays in inspections, and that the agency’s goal is to inspect each dam at least once every five years.

Six months after Harvey, the city of Ivanhoe was still struggling to figure out what to do about the partially collapsed dam in Campos’ backyard. TCEQ had suggested either repairing the dam, which could cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, or removing it. The latter was cheaper, but would mean losing the lake. Then, in March 2018, Mother Nature forced the city’s hand. A storm dumped 10 inches in the area overnight. Within hours the Ivanhoe lakes were full.

“We had said that [heavy rainfall like that from Harvey] just doesn’t happen very often, and here it had happened again within six months,” Bennett said.

Within months, the property owners association in Ivanhoe scraped together $18,000 to have the lake drained and the dam removed. But what about the other dams in Ivanhoe? “You pray, or you rebuild the whole dam,” Bennett said. And without the millions of dollars it would take to rebuild, the city seems resigned to prayers.

A degree of wishful thinking seems to underlie the state’s science on rainfall. In 2016, John Nielsen-Gammon, Texas’ state climatologist, was asked to peer-review a study commissioned by TCEQ’s dam safety division. It had been 40 years since the last study on extreme rainfall in Texas, which provides important guidance for sizing dams in flash-flood-prone Texas. In the meantime, many devastating, unprecedented floods had swept through the state.

TCEQ contracted with a Denver consulting firm to update rainfall data, but when the analysis reached Nielsen-Gammon for review, he was surprised to see that the firm hadn’t looked at how climate change would worsen rainfall in Texas. But that’s not unusual. Meteorologists haven’t yet devised a universally agreed-upon method to factor climate change into extreme rainfall analyses. “Without a standardized way to incorporate climate change, the approach is to assume that what happened historically is representative of what could happen in the future,” said Nielsen-Gammon.

But such an approach is problematic, particularly for Texas. Rainfall in the state is influenced by the Gulf of Mexico, a warm bathtub of an ocean that’s steadily warming. As oceans heat up, evaporation increases and storms have more fuel to gather before they make landfall. That makes climate change a key component in understanding extreme rainfall events.

“I was calling my neighbors, telling them we might have a wall of water in half an hour.”

Still, even without factoring in climate change, the TCEQ study found that worst-case rainfall scenarios are significantly worse for parts of the Gulf Coast and East Texas compared to the findings in the 1978 study. In East Texas, for instance, the most extreme rainfall events could result in 12 percent more rain for large drainage areas.

Perhaps not surprisingly, East Texas has also seen the most dam failures, the Observer found. More than 70 percent of all Texas dams that failed in the last century are in East Texas, despite the fact that the region has only 45 percent of the state’s dams. The analysis also found that of the 658 dams that TCEQ has assessed in East Texas, 542, or 82 percent, were in poor or fair condition.

How to use this map:

1. You can sort dams by their condition — satisfactory, fair or poor — and whether they’re regulated by using the menu to the left of the map. Make sure you select criteria for both condition and regulation.

2. Check the condition of dams in your neighborhood by using the search bar in the upper right corner of the map. You may need to zoom out a bit to see dams in your area. Click on an individual dam to see if it has ever failed, whether it’s regulated by the state and other information.

Morrow, the TCEQ spokesperson, said that the 2014 study indicates that some small watersheds may actually see less intense rainfall in the future, leaving some dams in a better position to weather storms.

But Hurricane Harvey is a recent reminder that failing to account for climate change is a dangerous oversight. For example, the TCEQ study considered the amount of rain that Harvey unleashed theoretically impossible. In fact, after Harvey, TCEQ revised its worst-case scenario rainfall numbers up by as much as 8 percent for some parts of Texas.

Nielsen-Gammon said that it’s vital to consider the risk of failure over the lifetime of infrastructure, especially with dams, which are expected to last 50 to 100 years and never fail.

“The more important the infrastructure, the more important the trends associated with climate change are,” he said.

But far from grappling with climate change, state regulators are struggling to keep tabs on thousands of Texas dams.

In the early 1970s, a developer called Empire Development Company carved Lake Deerwood Estates, a retirement and vacation community, out of a marshy enclave near Harleton in East Texas, 30 miles from the Louisiana border. Perhaps sensing that a lake could significantly boost home values and attract buyers, Empire Development dammed a small tributary of Brushy Creek, creating 25-acre Lake Deerwood. Now owned by the Lake Deerwood property owners association, the modest earthen dam measures 27 feet tall and 1,125 feet wide. When the lake was built, the only thing downstream was a county road, timber and pastureland. The design was simple, too. If the lake rose within five feet of the top of the dam, water would flow through a 16-inch pipe, under the road and into nearby fields. Lake Deerwood dam was typical of the almost 1,500 dams built in Texas in the 1970s: less than 50 feet tall, earthen and built for recreational purposes.

From the beginning, there were problems. At first, TCEQ inspectors saw what they described as “deficiencies of an ordinary nature.” Some sections were eroding and water appeared to be seeping through the base of the dam. A 1988 inspection found “moderate to severe erosion” near the 16-inch pipe. Still, TCEQ found that the structure had “no serious and/or hazardous conditions.”

For the next 12 years, TCEQ didn’t check on Lake Deerwood a single time. But in March 2010, internal TCEQ emails show, the agency got a call “from a concerned citizen” who complained that the dam was “unsafe” and that the president of the property owners association “will not repair dam due to [lack of] funds.” When TCEQ inspectors visited, they found that water jetting around the rusted-out 16-inch pipe had carved an 8-foot gully at the foot of the dam.

It was a serious issue, and TCEQ sprang into action. The agency asked Dwaine Lassiter, the manager of the Deerwood Estates property owners association, to lower the level of the lake and hire an engineer to draw up repair plans. But the POA had very little money, and by the time the community scraped together $6,000 to hire an engineer, the 82nd Legislature was underway in Austin.

Unbeknownst to Lassiter, a handful of powerful landowners were working at the Texas Capitol to strip state oversight of dams such as Lake Deerwood. During that session in 2011, Representative Charlie Geren, a Republican lawmaker from Fort Worth, introduced an amendment that would have exempted more than 5,100 dams — about 70 percent of the state’s inventory — from regulation.

The amendment had support from two prominent Texans, Ralph Duggins and Elton Bomer. Duggins was a private attorney in Fort Worth who would later be appointed by Governor Greg Abbott to a seat on the Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission. His family owns a farm south of Granbury on the outskirts of the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex. They’d built a dam on the property in 1977, creating a 30-acre lake for watering livestock. Bomer was a former Democratic lawmaker in the Texas House in the 1990s who also served as secretary of state under Governor George W. Bush. Like Duggins, Bomer also had a dam on his property that impounded an 18-acre lake.

“There’s more that’s going to fail. Maybe somebody’s grandpa bought a bulldozer … and scraped up a bunch of dirt. We don’t know a lot about a lot of these dams.”

Under Texas law, every dam in the state receives a “hazard classification” — low, significant or high — based on the population at risk downstream. If more homes and businesses are built in the inundation zone, TCEQ may bump up the hazard classification and require the owner to upgrade the dam. As Texas’ population grew, more and more dam owners, including Duggins and Bomer, were finding that their dams were no longer considered low-hazard and required upgrades.

Duggins told the Legislature that the dam safety rules were “arbitrary and unreasonable.” The agency was asking him to upgrade the dam to handle more rainfall, which would have cost tens of thousands of dollars. “Instead of the ranch handling 7 inches of rain in six hours, it is to handle 15.5 inches in six hours,” he told a House committee in 2011. “Nothing prevents [TCEQ] from coming back next year because someone built another house.”

By the end of the session, facing pushback, the Legislature passed a compromise bill that exempted low and significant hazard dams in rural areas. Lake Deerwood was among the 3,516 dams — 45 percent of the statewide total — that would no longer be regulated.

But the Legislature, in its infinite wisdom, did allow TCEQ to keep an eye on the exempted dams in case there was development downstream that moved the hazard classification to high. In 2011, based on satellite maps, TCEQ suspected that more homes had been built downstream of Lake Deerwood. The next year, in May 2012, an on-the-ground inspector confirmed that the dam was now high-hazard. He also found that no progress had been made on the upgrades and the dam was still “in poor condition.” It took TCEQ two years to formally reclassify the dam as high-hazard, and then another two years for an inspector to visit Lake Deerwood again. In the intervening years, Lassiter said the POA eventually replaced the faulty pipe, but admitted that it hadn’t followed the agency’s instructions to cover it up with earth. Meanwhile, the pipe remained exposed to the elements — another casualty of the state’s convoluted system of dam regulation.

Then came the gullywasher of March 2016 — 8 inches of rain in 48 hours. Water rushed through the exposed pipe and, unable to withstand the pressure, it came apart. Water then gushed out the side of the dam and eventually eroded a 50-foot hole. “It was digging a hole straight to China,” recalled Lassiter. Harrison County officials told residents downstream of the dam to evacuate. TCEQ refused to release maps showing homes that could have been flooded, but the Harrison County sheriff told reporters at the time that there were “about six residences at risk below that dam.”

Luckily, the dam didn’t completely collapse. But with such a close call, the POA once again set about repairing the dam. It installed a new 24-inch pipe and packed the 50-foot hole with clay and gravel. On one end of the dam, it built a spillway with compacted clay. The plans weren’t approved by a state-licensed engineer — a violation of state regulations, but TCEQ never held the POA responsible.

The 2016 flood was far from a worst-case scenario. According to TCEQ’s latest rainfall data, a maximal rain event would result in 41 inches of rain over 24 hours or 44 inches over 48 hours. Morrow said the dam is scheduled for inspection within the next six months and “any issues associated with the spillway will be addressed at that time.”

As with the Lake Deerwood dam, downstream residents often don’t know if they’re in danger. The state closely guards information about dams, including a dam’s hazard classification and whether it was built to withstand extreme flooding. In response to an Observer records request, TCEQ told the Texas attorney general that releasing such information could “facilitate an act of terrorism resulting in catastrophic property damage or mass casualties.” The attorney general ruled in favor of TCEQ.

But the agency’s concern about small-dam terrorism did not extend to its redaction efforts. In August, TCEQ inadvertently released the hazard classification for 16 dams in response to a different records request. Improper redactions allowed the Observer to note that a handful of dams on Plum and Denton creeks in fast-growing Hays and Wise counties are considered high-hazard.

Texas’ dam-building era is over. Of the 7,200 dams in the state, more than three-fourths were built before 1975. The aging infrastructure has earned Texas dams a “D” grade from the American Society of Civil Engineers. In 2016, TCEQ estimated that updating the approximately 1,000 dams with the greatest potential to hurt people would cost $2.5 billion.

At a recent Texas Senate hearing, officials with the Texas Soil and Water Conservation Board, which works with landowners to maintain about 2,000 dams built by the federal Department of Agriculture, told lawmakers that of the 611 high-hazard dams that fall under its purview, 488 don’t meet safety criteria needed to adequately protect lives downstream. Rex Isom, the board’s executive director, said legislative appropriations “do a little bit of work, but it’s not a drop in the bucket to the overall problem.”

Some communities have taken matters into their own hands. The affluent city of McKinney, 40 miles north of Dallas, is one example. In 1999, the city passed a stormwater management ordinance that restricts development downstream of dams in the breach zone. It also requires upstream developers planning to pave over prairies and increase impervious cover to contribute to the cost of dam rehabilitation.

“It was digging a hole straight to China.”

Michael Hebert, the assistant director of engineering for the city, estimated that builders are typically pitching in between $500 and $1,000 per acre. So far, Hebert estimated, the city has spent over $4 million upgrading dams.

“Our development community has been 100 percent behind us,” said Hebert. “Our ordinance says we encourage you to develop, but we need to protect the infrastructure. They recognize that they’re protecting downstream residents.”

Plus, the city has been successful at securing more than $10 million in state and federal grants for repairs and upgrades. In contrast, Ivanhoe is a long way from seeing that kind of money. The town’s dams were originally built by a developer in the late 1950s, and for the next five decades the property owners association was responsible for all five dams now within the city limits. The POA set the maintenance fee per lot at $6 a year — a paltry sum that generates only about $23,000 a year to maintain Ivanhoe’s 12 parks, 60 miles of roads and five dams.

In 1996, after Lake Charmaine dam failed, the association had nowhere near the $1 million needed to rebuild the dam. When the POA tried to raise the maintenance fee in the early 2000s, a group of homeowners sued and derailed the plans. Eventually, in 2009, the community voted to incorporate as a city and use taxes to fund upgrades.

Even with the tax revenue, Bennett, Ivanhoe’s mayor, said the city’s $500,000 budget isn’t enough. “It is stressful,” she said. “There’s not enough money to fix the problems we have.” And the problems have been persistent. Since 2005, TCEQ has inspected Lake Charmaine dam three times. Each time inspectors have pointed out serious problems with the dam and given it the lowest safety rating. In 2012, for instance, inspectors found cracks in the dam and telltale signs that water was traveling underneath the structure. When TCEQ inspected it again in 2017, after Harvey, it found the same problems. Inspectors noted that “a significant storm event could raise the water level and head pressure to accelerate any piping … and allow an uncontrolled loss of the reservoir.”

Morrow, the TCEQ spokesperson, said the agency considered Lake Charmaine dam to be “hydraulically adequate,” and that the agency only takes enforcement action if dams are a threat to life and their owner refuses to address the issue. She pointed to Ivanhoe’s dam inspector, Rusty Harrison, who conducts monthly inspections, as evidence the city is taking a proactive approach.

Harrison, who is not a professional engineer, told the Observer in an interview that water and sand still bubble through the downstream end of the dam, but it would cost $10,000 to $15,000 to implement the upgrades recommended by TCEQ — and the dam isn’t a priority at the moment for the city. Though four buildings are located downstream, Harrison dismissed the threat, saying that people’s lives are “always at risk.”

“You can’t justify the cost of the installation, because [a big storm] event is only going to happen every 15 to 20 years,” he said. “It’s not worth the effort.” Asked what might happen if a dam failure hurts someone, he said that “normally [people] get hurt by their own hand,” and “a lot of times, it’s not the storm.”

This article was reported in partnership with the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

Caption for top photo: In March 2016, the Lake Deerwood watershed saw 8 inches of rain over two days. The force of the floodwaters dug a 50-foot wide hole on the downstream end of the dam.