Dem Candidate for Harris County DA Says Domestic Violence is ‘Overrated’

Oliver doesn’t just hold some old-fashioned ideas about family violence. He makes it clear that he wants to be Harris County DA to reduce prosecution of domestic abuse.

Lloyd Oliver can’t convince me that Harris County should prosecute fewer domestic violence cases, and it is driving him nuts.

“Family violence is so, so overrated,” he says, sitting across from me at a Starbucks. “This here”—he leans over and taps the back of my hand—”is an act of family violence in accordance with their, what they’re doing up there now. Just me touching you.”

Hear Lloyd Oliver talk about what defines family violence.

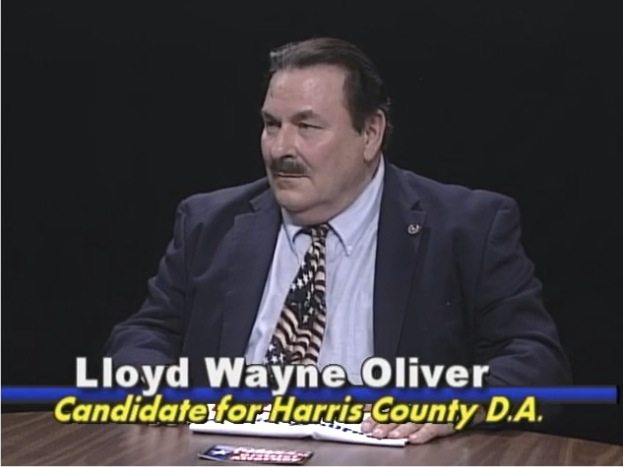

Oliver, 70, has been a criminal defense trial lawyer for about 40 years and he looks the part. In a dark suit with a striped shirt and striped tie, with the tiniest point of a red and blue pocket square peeking out, Oliver seems both professional and kind. His face looks radiantly clean, as if scrubbed, and his ruddy cheeks bring out his bright, clear, friendly blue eyes. When he talks, which he does a lot, he looks right at me, never glancing away. Although once his phone rings and the caller ID reads “Miss Piggly Wiggly,” Oliver stays focused, gauging my reactions, tweaking his argument as he goes. He is, in short, one hell of a trial lawyer.

He’s also a perennial candidate, having run five times (unsuccessfully) in Harris County for judge as both a Democrat and a Republican. But he’s no dark horse. In 2012, he beat a highly qualified, heavily favored candidate in the Democratic primary for Harris County district attorney. That opponent, Zach Fertitta, had been an assistant DA for nine years and spent about $100,000 campaigning. Oliver spent $300 on flyers. Yet he didn’t just win the Democratic nomination; he came within five points of winning the general election.

This year, Oliver faces Kim Ogg, a board-certified felony prosecutor who oversaw a 40-percent drop in gang violence as director of Houston’s first anti-gang task force. She went on to work as executive director of Crime Stoppers. Oliver characterizes this as a weakness. “She hasn’t tried a case in I don’t know when…” Oliver says. “You bring nothing to the match. No experience.”

But Ogg does bring support from the political establishment, including some Republicans. The Houston Chronicle’s conservative political blogger, Big Jolly, called her announcement “awesome,” citing her plans to reduce jail overcrowding by diverting people with mental illness and increasing alternative sentencing for minor drug convictions. It’s a popular platform. Like her defeated forerunner, Ogg has raised more than $100,000 and campaigned vigorously since October. Oliver hasn’t.

In a recent interview, he told the Chronicle, “It’s my race to lose. My strategy is to watch a lot of TV, I think. That’s all I’ve been doing.” The Chronicle’s editorial board was unimpressed. The penultimate sentence of their endorsement of Ogg read, “Primary voters should give Oliver the thrashing he deserves for making a mockery of our elections.”

Oliver admits he runs for office to drum up business for his law practice. He credits his 2012 win to name recognition and “dumb luck,” though some political observers thought it may have been because voters assumed, from his name, that Oliver was black. This theory was undermined by broad support from non-minority districts. Why ever Oliver won, it wasn’t because of good press. The media spilled lots of ink on Oliver’s checkered past and unorthodox style. In his long career, Oliver has been suspended twice and indicted twice for barratry (paying someone to refer clients) and once for bribery, though he’s never been convicted.

Oliver’s most written-about scandals are linguistic. In a 2012 interview with the Houston Press, he used terms like “queers” and “rag heads” and called the local Democratic leadership “frustrated homosexuals” for trying to kick him off the ballot. (After he won the nomination, party leaders decided they would rather run nobody. Oliver sued to get back his spot.)

Among his least popular public statements was that maybe victims of domestic violence should “learn how to box a little better” and that battery can be a “prelude to lovemaking.” This went over poorly, especially when he reiterated these thoughts at a debate hosted by the Harris County Domestic Violence Coordinating Council.

But I didn’t meet with Oliver to talk about domestic violence. I wanted to know why he’s running for district attorney and what he’d do if he got the job. For all his press, I had no sense of his platform.

Within 10 minutes of our meeting, though, I learn that domestic violence is his platform. “That’s my issue, right there,” Oliver says. “An inordinate amount of time [is] spent on that when we could get more criminals out of Harris County by doing what I suggest, I guarantee.”

Oliver suggests trying more cases instead of accepting pleas and trying them much faster. “The district attorney will have a trial going at every court at every hour every day when I’m elected,” he says. “Justice delayed is just no damn justice at all. And that’s what I see. You see those damn filthy baby-rapers—they get tried, what, nine months later? A year later? Why not two months later? How long does it take to prepare a case?”

Oliver uses the term “baby-rapers” six times during our 70-minute interview. Eventually, he seems to notice this and throws in “aggravated sexual assault of a child.” It’s a move I imagine is effective with juries trying domestic violence cases. Oliver estimates that a quarter of the people he defends are charged with family violence, and as we sit together he delivers a series of vigorous, well-rehearsed arguments for why spousal abuse is taken too seriously.

What does this have to do with speedy trials? As district attorney, Oliver would divert resources away from family violence to try other cases, particularly when the abuse victim doesn’t want to press charges. “You don’t want to pursue it,” he says. “I don’t want to pursue it. The children are crying, ‘Please don’t take my dad to jail.’ And we’re pursuing things like that? That’s where we’re wasting our money? Oh, and our time? Why don’t we go after those baby-rapers instead?” He pounds on the table with each word of this apparent closing argument. “Let’s. Put. Those. People. In. Jail.”

Oliver says he would prosecute assault, but that most family violence cases aren’t really assault. “To me, an assault is not something where, in a relationship—it’s not a pushing, shoving match…” he says. “Assault should be enforced. But me touching you, pushing, shoving, some kind of mutual combat, not even combat [but] a mutual scuffle,” shouldn’t.

Oliver feels only “one in ten cases” of family violence warrants jail time or prison. “Because not every shoving, every touching, even though it’s unpermitted, is an assault, and that’s the way things are handled now. An unpermitted touching becomes an assault.”

Even some acts that are assaults shouldn’t be prosecuted because they’re deserved, Oliver says.

“So your husband…” he begins. “You slap him. He comes home, 2:00, and he smells like some woman’s perfume and you whack him upside the head. You know what? He probably deserves it…. But technically that’s an assault. It’s an assault, family violence. Technically you’d get arrested and go to jail for that. Is that silly or what?”

Later he adds, “Most of the men that I know that are victims of some women whipping their ass, they deserved it. Alright?”

Oliver says he’s “whipped a few men” and “been whipped a number of times by a man.” He acknowledges, “Those were assaults. They sure were. And I deserved most of them.”

But he’s especially emphatic that cases where a victim doesn’t want to press charges are victimless.

Say a couple is engaged in a “mutual scuffle” and the police arrive. “Guess what? I’m going to jail” he says. “And then you said, ‘Please don’t take my husband to jail. It’s just a dispute between he and I…. I’m not hurt. There’s no blood, there’s no hospital, there’s no ambulance, there’s no nothing.’ Yet they prosecute that.”

Oliver looks amazed. “If it’s the second time this guy in his lifetime has had one of those, they prosecute it like a felony. Why are felony dockets clogged up with something like that? There’s no victim, if you will. There’s no victim.”

Hear Lloyd Oliver discuss victims of domestic violence.

Amy Smith disagrees. She’s deputy director of the Harris County Domestic Violence Coordinating Council and used to head the Harris County DA’s family violence victim witness division. “If there’s not evidence of injury, he’s not going to be arrested for assault,” she says. “The [cases] that end up in the DA’s office, there has to be some evidence to support that… A police officer came to the scene, decided they were going to call the DA’s office. The DA’s office felt there was enough probable cause to file a charge. They filed a charge and if it’s a misdemeanor, it gets reviewed. If it’s a felony, it goes to a grand jury. If it goes to a grand jury and he’s indicted, that’s another check. And then it goes to trial.”

“There are reasons the laws are in place,” Smith says. “[Harris County] had 30 women killed in 2012. That’s a lot of women.” In fact, it’s more than a quarter of all the women murdered by their partners in Texas that year. “There were 36,000 reports to law enforcement…. We know that domestic violence is the most under-reported crime. So if you think of the fact that there were 36,000 domestic violence calls, you can think of how many people didn’t call.”

As for whether to prosecute cases where the victim doesn’t want to, Smith says, “It could be that he’s standing behind the victim while she’s on the phone saying, ‘I want to drop the charges.’ It could be that he said, ‘Oh honey, I’ll never do that again’ as she’s signing the affidavit of non-prosecution. I think what Mr. Oliver doesn’t understand is that domestic violence is about power and control. It’s not just about violence.”

After Oliver says “there’s no victim” a second time, he sits back, satisfied. It’s another closing-argument moment. But then he sees I’m not convinced. He hunches forward, launching into a new angle.

“Here’s what happens,” he says, gesturing with both hands. “The children become the victim. The chil-dren.”

I ask, “The children become a victim of the dad going to jail, or the children become a victim of there being violence in their house?”

“The children become the victim of hauling Dad away, and maybe Mom too, because they get in a pushing match,” he says. “They get in a verbal argument, a verbal altercation, that, uh, finally resorts to him pushing, her pushing. And now they haul him away. Okay? Now he lost his job. They lose their little apartment. They lose their house. They lose everything. Their kids are disrupted. Their family is disrupted. He can’t come around for, what, 30 to 60 days, can’t even come around the house? Can’t support two households. They lose everything. And again, the victim is who? The children become the victim. The chil-dren. What about the babies, alright?”

At one point, I note that many victims defend their abusers because of fear, economic dependence, or other manipulation. “It’s pretty common, right?” I say.

“Uh, it’s called marriage,” he says and laughs.

“Okay…”

“Or life….” he says. “And you shoving me doesn’t bother me, it doesn’t offend you, let’s leave it alone. It’s called marriage.”

Several times, I try to change the subject. Would he continue the current DA’s policy of prosecuting possession of trace amounts of crack cocaine as a felony?

“Case-by-case basis,” he says. If someone’s caught with a trace amount and has a long criminal history, “It’s probably yours. So on a case-by-case basis, that’s the way we should handle it. But not just blanket, go out there and arrest the man, put him in jail, disrupts the family and everyone, everyone’s crying and unhappy,” he says. I realize he’s talking about domestic violence again. “That doesn’t solve anything…. There’s underlying issues. Number one, I see a lot of this. It’s really not his temper or the fact that she’s just a raving bitch this time of the month. That ain’t it. Underlying issue is alcohol. Most of ‘em been drinkin’.”

When I ask why he’s running as a Democrat rather than a Republican he says, “Is there a difference?” Then he admits, “There’s more accessibility in the Democratic Party…. I enjoy a good fight. I love a fight. I don’t like fightin’ with my spouse, but I like fightin’ with most everyone else. When I fight with my spouse she always wins. So I leave her alone.”

But Oliver has been divorced three times and has no spouse.

Finally I ask why he’d leave criminal defense. “I love to see justice done,” he says, then returns to family violence. “I love to see some man and his wife and children put back together again, and their relationship, they’re working on their relationship to make it better, better, better.” He pounds the table. “And maybe there’s an act of violence. Maybe there’s a positive side to that. They get help and the family stays together. … And if the law is stupid, let’s reform it. It is stupid. It’s stupid.”

To Oliver, assault usually isn’t assault. Or else it’s mutual. Or it’s deserved. Or it’s alcohol’s fault. Or it’s the first time. Or it’s by a woman. Or the victim doesn’t mind. Or punishing the abuser would do more harm than good. Oliver doesn’t just hold some old-fashioned ideas about family violence. For more than an hour, he makes it clear that he wants to be Harris County DA to reduce prosecution of domestic abuse.

As for that one case out of ten—the severe, repeat offender, the one who “really worked her over that second time”—Oliver has a different plan. “He needs some help too. And he can achieve that [in prison] doing two to ten. He’ll get a lot of help there. He can get all the, he can beat up all the, he can beat his wife up in there.” Oliver laughs. “Because he’ll find a wife in there, and let him work that wife over.”

Hear Lloyd Oliver discuss violence in prisons.