Despite Public Health Risks, Trump’s EPA to Roll Back Regulation to Prevent Methane Leaks

The Obama-era regulation is meant to curb leaks of methane, which is about 30 times more potent than carbon dioxide.

Last week, the staff of the environmental nonprofit Earthworks were on a retreat in West Texas when Sharon Wilson, a Dallas-based organizer for the group, decided to take them into the Wild, Wild West of the Permian Basin. A certified thermographer, Wilson has traveled endlessly across Texas documenting the environmental and public health consequences of living near oil and gas operations. As a landowner in Wise County, which overlies the gas-rich Barnett Shale, she had a front-row seat to the rise of fracking. With about 20 staffers packed in three vehicles, Wilson drove down Highway 17 out of Balmorhea from site to site, aiming her thermal-imaging camera at the methane escaping from stacks and leaky tanks at storage and processing facilities. In some cases, the leaks looked like a dripping faucet. In other cases, methane was gushing like a fire hose.

“It’s just crazy what I‘m seeing,” Wilson said. “It’s the worst emissions I’ve seen anywhere.”

The problem is likely set to get worse. The Trump administration is in the process of reversing Obama-era regulations that require routine leak checks and technological improvements to prevent methane from escaping from pipelines and well sites. The official announcement from the EPA is expected this month. That means in shale plays across the state, and in small towns such as Balmorhea — where fracking is expanding up to the doorstep of the famed Balmorhea swimming hole — methane leaks are set to continue, with significant consequences for both air quality and public health.

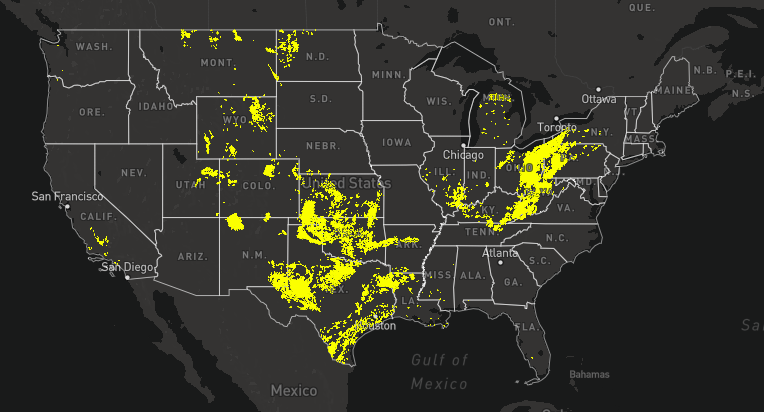

Methane, which is about 30 times more potent than carbon dioxide, is a major driver of climate change. Curbing methane emissions also has the benefit of decreasing volatile organic compounds, including carcinogens such as benzene and toluene that can cause respiratory illnesses, nausea and nosebleeds. According to an analysis by Earthworks, 2.3 million Texans live within a half-mile of an oil and gas facility. More than 900 schools and 75 medical facilities are also in the half-mile radius.

About a decade ago, during the early years of the fracking boom, natural gas was heralded as a clean fuel that could bridge the transition from dirty coal to renewables. Though researchers disagree about the exact amount, studies have found that up to 12 percent of natural gas that is produced ultimately escapes into the atmosphere. Depending on the amount, natural gas may burn cleaner than coal, but methane leaks during extraction and refining might cancel out much, if not all, of the climate benefits.

Leaks can occur in a number of ways: from wells as natural gas is being extracted, as it’s transported through pipelines, while it’s stored in tanks and from unlit flares that vent gas instead of burning it. The Obama EPA regulations require oil and gas operators to monitor sites for leaks at least twice a year, use new technologies to monitor leaks remotely and fix leaks once detected. The EPA expected that these strategies would reduce methane emissions by 510,000 tons in 2025 — causing the equivalent harm of 11 million metric tons of carbon dioxide. The agency estimated that the upgrades would cost owners of the facilities $530 million, but the benefits to air quality and preventing climate change outweighed the costs by $160 million.

In 2017, soon after Trump appointed former Oklahoma attorney general Scott Pruitt to head the EPA, the agency announced it would stop the implementation of the rule. Environmental groups sued over what they claimed was an unlawful “stay” and the courts sided with them. As a result, the rule is still on the books, but the EPA is not enforcing it. In place of federal action, some states such as Colorado, Ohio and Pennsylvania have stepped in to enact their own state regulations to reduce methane leaks.

“It’s the worst emissions I’ve seen anywhere.”

Texas isn’t one of those states. In 2016, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton sued the EPA over the regulation, calling it “a gross demonstration of federal overreach.” Paxton later said the EPA’s efforts to collect data on methane leaks from the oil and gas industry constituted “harassment.”

“Many companies involved with this request cannot afford the time and expense of complying with an empty, heavily regulatory burden,” Paxton said. “The information request puts strain on these companies — and all for the purpose of supporting an unlawful rule.”

For Lauren Pagel, Earthworks’ policy director, Texas is a prime example of where federal action can help address methane leaks. “It’s been pretty clear that Texas isn’t going to be leading or even following in terms of state regulations,” she said.

Still, some operators are choosing to comply with the regulations anyway. In February, XTO Energy, a subsidiary of ExxonMobil, announced that it supported methane regulations. “The correct mix of policies and regulations could help the entire industry raise the bar,” wrote Sara Ortwein, XTO’s CEO. Ortwein also proposed “key principles” similar to the EPA regulations to detect leaks quickly and reduce emissions overall. Then, last month, Exxon announced that it expects to decrease methane emissions by 15 percent and flaring by 25 percent by 2020.

Why would the EPA torch a regulation that some of the largest oil and gas companies are embracing? Pagel said it’s just part of the politics of the Trump administration. “Some of what’s going on at EPA is rolling back anything the Obama administration has done, regardless of whether it’s good policy or not,” she said.

Correction: This post has been updated to remove New Mexico from a list of states that have enacted methane regulations.