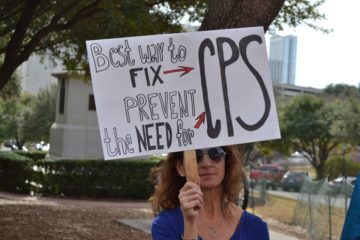

Despite Warnings, the Texas Legislature Plans to Privatize Much of the Child Welfare System

Pressure from the governor to get CPS reforms passed quickly has hushed most criticism of the $279 million privatization plan.

Under pressure from the governor, advocates and a federal court, lawmakers are moving at breakneck speed to address the state’s failing child welfare system. But in doing so, they may be rushing into a privatization scheme that could plunge Child Protective Services (CPS) into crisis again.

In 2016, more than 200 children died of abuse and neglect in Texas. On any given day, there are hundreds of kids who are in imminent danger, yet go unseen by a caseworker with CPS, the troubled state agency that is responsible for protecting maltreated children through social services like foster care. For the children who are rescued, it’s possible they’ll end up sleeping in a hotel or CPS office because there aren’t enough foster homes.

Both chambers of the Texas Legislature are considering legislation that would privatize big parts of CPS. Senate Bill 11, which won preliminary approval in the Senate on Wednesday, and House Bill 6 would put regional nonprofits in charge of case management and kinship placements, duties currently performed by state workers. Both bills would also expand a more limited privatization pilot program in the Fort Worth area.

The Department of Family and Protective Services, CPS’ parent agency, estimates that privatization will cost nearly $279 million over the next five years. Though legislators are quick to acknowledge that child welfare reform is going to be costly, budget writers have yet to allocate any additional money for the expanded privatization efforts.

Wayne Carson, the CEO of the nonprofit in charge of the Fort Worth pilot program, says privatizing case management, in particular, is the logical next step for improving child welfare in Texas. Currently, the state decides what a foster child needs, and Carson’s organization then provides the homes and services.

“If one entity is managing both sides of that equation, we can coordinate care better,” Carson told the Senate Health and Human Services Committee last month.

But some child welfare advocates say that pushing case management to the private sector is a dangerous move.

“They’re going to take work that’s been done by public employees in an organization that it’s taken decades to build and they’re going to turn it over to nonprofit corporations who have no experience in the job whatsoever,” said Scott McCown, a former state district judge and the director of the Children’s Rights Clinic at the University of Texas.

Case managers, also called CPS conservatorship workers, decide what kind of home a foster child is placed in and what services they will receive. They also make final recommendations to the court regarding termination of parental rights, adoption or family reunification.

“It’s just shocking to think that the state of Texas would delegate its sovereign authority to a private corporation and give the private corporation money — state money, public money,” McCown said.

Those familiar with CPS worry about how introducing financial incentives might influence sensitive decisions.

“When the one making final recommendations to the judge has a financial stake in the outcome, they’re going to get money based on their decision-making,” said Barbara Elias-Perciful, the director of Texas Lawyers for Children. “The system has inherent conflicts of interest in it and there isn’t any way to get rid of those conflicts.”

Proponents of privatization point to provisions in the legislation requiring a strict review of all potential contractors as well as performance benchmarks and a dedicated oversight committee.

Senator Charles Schwertner, the Republican carrying SB 11, told fellow senators this week that the safeguards “indicate that those conflicts of interest are probably not occurring.”

Still, advocates say such measures aren’t enough to protect kids.

“It’s very difficult to manage human services through performance-based contracts,” McCown said. “It’s hard to state what the right incentives are. We want kids to go home, except when we don’t. We want kids to go with relatives, except when we don’t. You’re making case-by-case decisions and nobody knows what the right numbers are.”

Elias-Perciful says the worst-case scenario is that gross abuses go unnoticed because the performance measures are being met.

“Let’s say that a child was sexually abused in a foster home and this information has not come to light,” said Elias-Perciful. “But that child may be attending school, may even be doing well in school, may achieve permanency and be put in a permanent home quickly.”

On paper, a case like that could still be considered a “success” for the contractor. They’d be rewarded with the continued flow of taxpayer dollars.

Such concerns are not entirely lost on lawmakers. Several have expressed trepidation with further outsourcing foster care, but pressure from the governor to get CPS reforms passed quickly has hushed most criticism.