Dressed in a blue blazer and khaki slacks, with sunglasses hanging from his button-down, Paul Gauthier approached the podium inside a conference center in Leander, a suburban community just northwest of Austin. A local conservative rabble-rouser with salt-and-pepper hair slicked back, he came to the September school board meeting to air his grievances.

“I have been trying to save this board for some time,” Gauthier said, speaking to the seven elected trustees. He then quoted the Bible: “I will strike down upon thee with great vengeance and furious anger those who attempt to poison and destroy my brothers.”

Gloria Gonzales-Dholakia, a 49-year-old Latina who was elected to the board in 2018, figured she would have to cover 20 feet to escape through the back exit. “Who are they going to execute in this room?” she wondered, remembering that her three children were watching the meeting on livestream at home. “Where would I hide if someone pulled out a gun?” (Reached by phone, Gauthier said he didn’t intend to threaten anyone.)

Members of the Leander Independent School District are used to Gauthier’s incendiary rhetoric. Around Christmas, he showed up at a board meeting dressed as Santa Claus, chastising trustees for being “naughty.” He has complained about everything from the school’s overspending to mask mandates to library books, in one instance reading a passage from All Boys Aren’t Blue, a memoir written by a Black gay author. Gauthier would like to see the book banned from Leander schools’ library shelves because it depicts sex acts.

Threats and angry tirades from conservative activists have become commonplace at school board meetings across the state. They come to protest the teaching of critical race theory—a school of academic thought that posits that racism is hardwired into society—to remove books they deem “pornographic” from school libraries and to generally harangue school faculty and staff they believe are pushing a liberal agenda. At Eanes Independent School District in Travis County, a rowdy crowd of adults taunted a high school student for expressing support for greater diversity education, which culminated in one attendee trying to take the microphone from her.

The culture warriors also come to protest COVID-19 precautions. In Round Rock, two men were arrested at a September school board meeting about the district’s mask mandate. One of the men derailed the meeting, shouting, “Communists! Communists!” and allegedly tried to push his way past a police officer before being taken into custody. This backlash comes as the pandemic has brought public schools to their knees, devastating staffing levels while administrators and school boards struggle to weigh the value of in-person education against public health concerns.

While it may be tempting to see these confrontations as a grassroots movement—and Republican politicians have cited them as such—much of the activists’ rhetoric comes straight from the mouths of the state’s GOP lawmakers. In fact, groups like Citizens Renewing America have cropped up across Texas to train activists to disrupt school board meetings, arming them with copy-and-paste talking points. In North Texas, a handful of familiar faces have made the rounds at meetings across the area. According to a Ballotpedia report, activists launched at least 92 recall attempts against 237 school board members nationwide in 2021. In Houston ISD, they were able to flip two seats; in Carroll ISD, they captured a majority of the board.

Public schools have become lodestones for the nation’s accelerating culture wars. Advocates for public education, along with lawmakers and experts, say this is merely the latest incarnation of a decades-old Republican playbook to discredit, defund, and ultimately destroy the Texas public education system.

Charlie Johnson, a reverend who directs Pastors for Texas Children, calls the state “ground zero” for what’s shaped up to be a nationwide war against traditional schools. “If they can destroy public education in Texas, they can destroy it in America and privatize it for their own personal gain, financial and otherwise,” Johnson said.

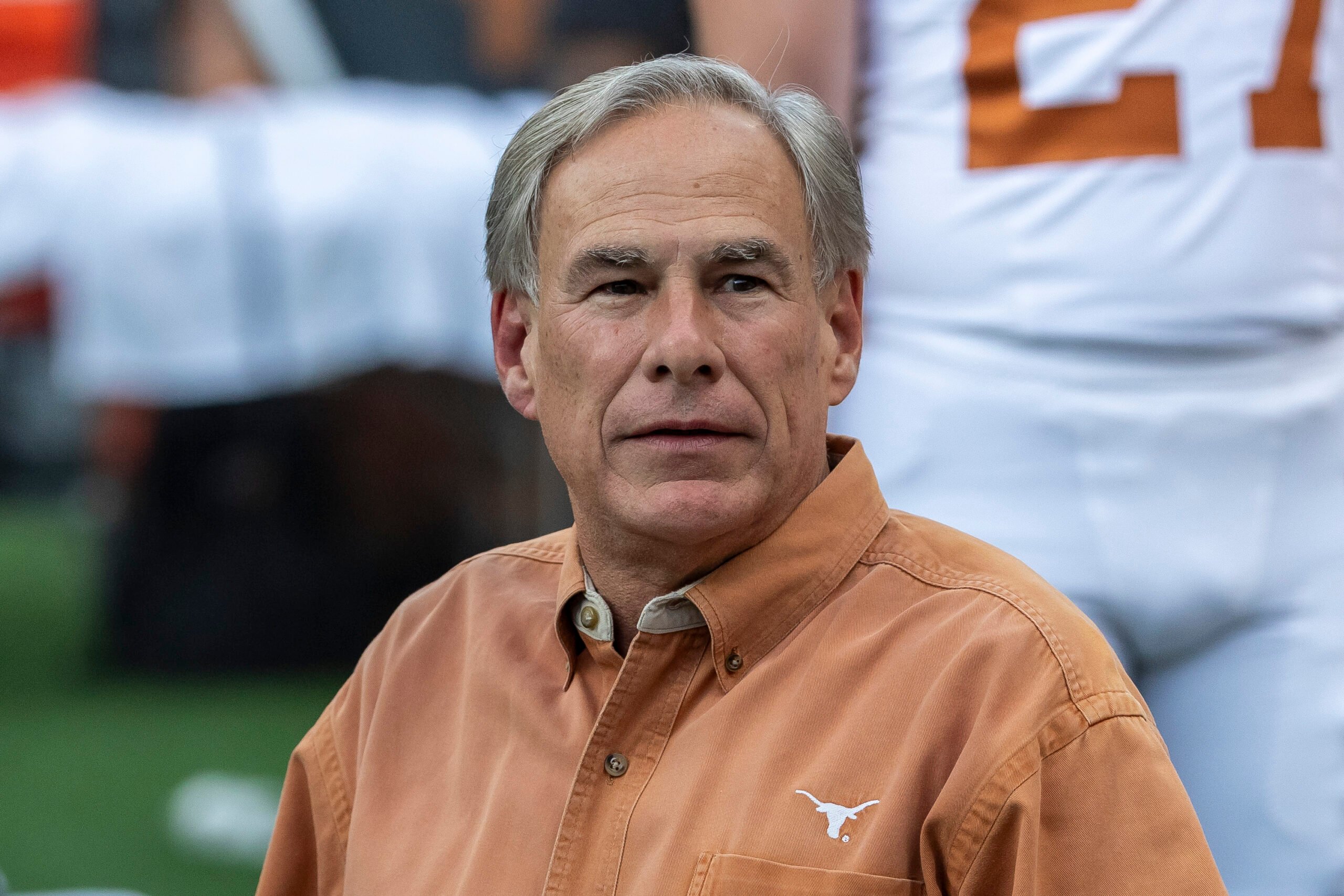

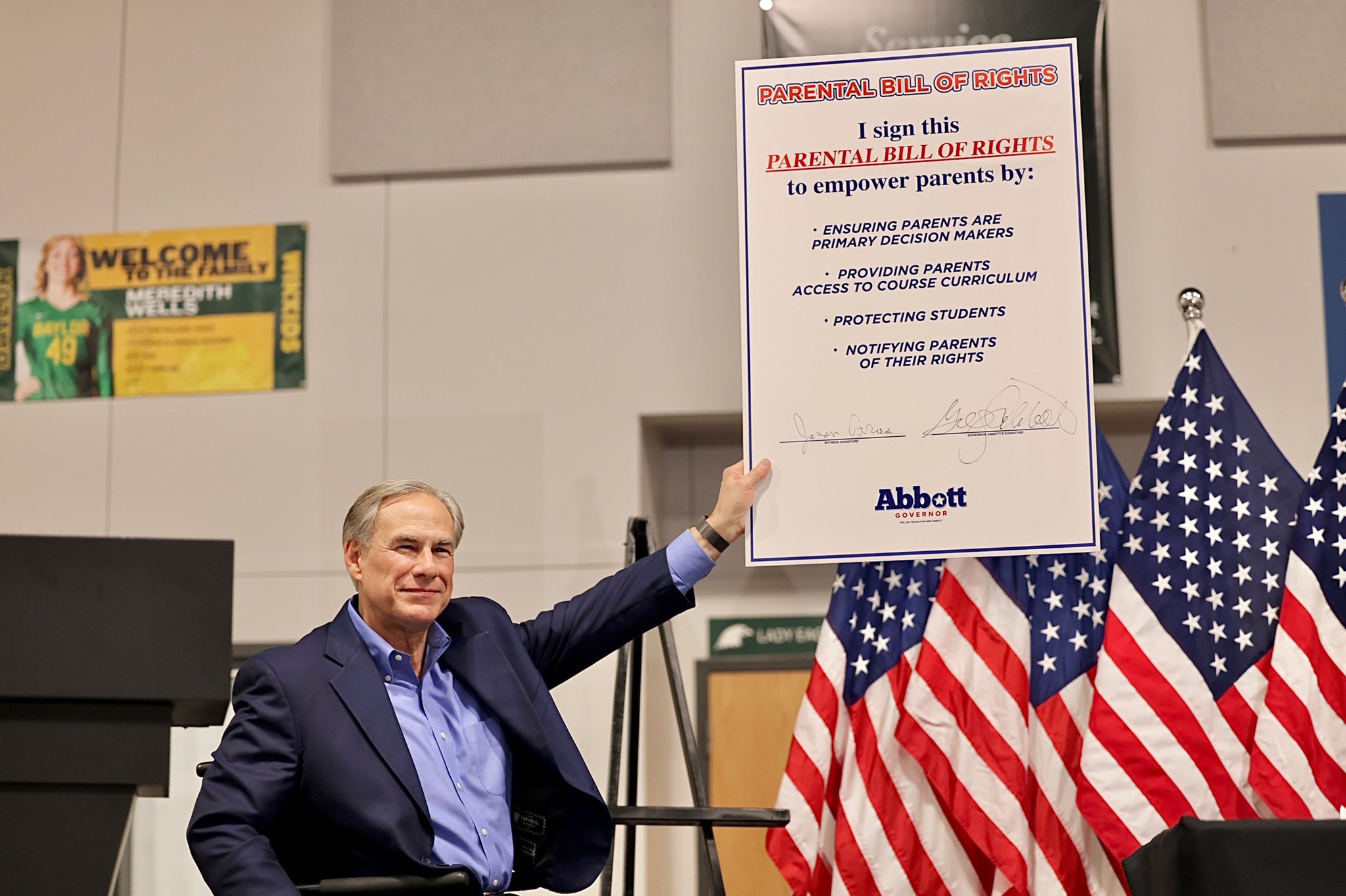

Republican officials like Governor Greg Abbott and Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick have supported the state’s ban on teaching the history of racism, House Bill 3979, and the current effort to remove hundreds of books from school shelves that state legislators deem “pornographic,” including renowned works by LGBTQ+ and minority authors. In January, Abbott announced he would seek to amend the state constitution with a “Parental Bill of Rights” that would blackball teachers accused of teaching “pornography” and strip them of their pensions.

National Republican figures from Texas are also doing their part to push the narrative. “In too many instances, you have left-wing educators putting explicit pornography in front of kids. I think that is severely misguided,” U.S. Senator Ted Cruz said in February.

For groups like influential conservative think tank the Heritage Foundation, the current culture-war battles offer a pretext to turn parents against schools and defund public education in the form of vouchers—stipends paid by the state for public school students to transfer to private, often religious, institutions.

“It is time for the school choice movement to embrace the culture war,” reads a February report from Heritage. “Advocacy groups would be foolish not to promote choice as a solution that can connect large majorities of parents with schools that align with their values—especially when public schools are not meeting their needs.”

The state’s political atmosphere is now ripe for Republican forces who want to take public schools down. While the Texas House voted last year to ban vouchers, the legislation failed to become law. Vouchers have long been part of the state’s Republican Party platform. Support for vouchers abounded in this year’s Republican primaries. Former Texas GOP Chairman Allen West made “school choice” legislation a top priority in his failed campaign for governor. Both Abbott and Patrick have expressed support for them in the past. Abbott told a crowd at a Dallas-area charter school in January that he also would push for a voucher-esque bill. Legislation regarding “school choice” or vouchers has been introduced in every legislative session since 1995.

The fight over private-school vouchers represents one of the nastiest and longest-standing political battles in the history of state lawmaking. Tensions over masks and progressive historiography are now a Trojan Horse, furnishing new troops for the privatizers’ side, and school district leaders, teachers, and working-class Texans all over the state may be among the casualties.

Depending whom you ask, the contemporary crusade against public schools in Texas began around 1997, a quarter century ago. That was the first year school vouchers really gained traction—a proposed voucher bill failed by only one vote in the state House. Though the measure was beaten back, the seed was planted.

In 2003, Midland Republican lawmaker Tom Craddick became speaker of the House after his party won a majority in the lower chamber for the first time since Reconstruction. Craddick delegated the task of drumming up voucher votes to Kent Grusendorf, an Arlington lawmaker who chaired the House Public Education Committee. Grusendorf, in turn, sought the aid of Jim Leininger, a physician and part-owner of the San Antonio Spurs who had already dipped into his personal fortune to elect politicians sympathetic to his cause: using vouchers to move kids from public schools to private ones.

Two years later, under Craddick’s leadership, the vehicle for Texas’ private voucher program became a reauthorization bill for the Texas Education Agency. Hidden in the bill’s language was a measure to use $600 million in taxpayer money to create a voucher pilot program in eight urban school districts. The voucher proposal died in dramatic fashion in the House that year. Representatives Carter Casteel and Charlie Geren used astute political maneuvering to turn enough other House Republicans to their side to sink the measure.

Voucher momentum then encountered more headwinds when an unlikely group of parents, advocates, and political newcomers banded together to protect public schools from the forces that sought to erode them. Texas Parent PAC, co-founded by journalist-turned-advocate Carolyn Boyle, launched a successful grassroots campaign to oust pro-privatization lawmakers. Boyle and her group were able to topple Grusendorf and win a couple of other races in spite of their opponents’ largesse.

“For people to be receptive to dramatic change in public education, there have to be clear problems with public education that hurt the students and the parents,” said Brandon Rottinghaus, a professor of political science at the University of Houston. Once problems have accumulated, or been ginned up, voucher supporters can offer “a better way,” he said.

Though voucher bills continued to be filed, the issue seemed to go quiet after the 2005 legislative session. That is, until Dan Patrick entered the picture.

Patrick, a former state senator from Houston and the current lieutenant governor, has been trying to get vouchers rolling in Texas since at least 2012, when he arranged for select voucher proponents—including a fellow at the Koch brothers–backed Texas Public Policy Foundation—to testify on the topic before the Senate Education Committee. Back then, he called school choice the “civil rights issue of our time.” A year later, Patrick was chair of the committee, making it easier for him to push his agenda and make life harder for urban school districts. In 2017, Patrick tried, and failed, to tack voucher language onto House school finance bills. “It was backdoor vouchers,” explained Luis Figueroa, legislative and policy director for the liberal think tank Every Texan.

Patrick has yet to see his voucher aims realized, in part thanks to resistance from within his own ranks. Unlike the reactionary suburbs and exurbs where Patrick thrives, school districts in rural Texas are frequently the largest employers and sometimes the sole bright spots in communities where hospitals, local businesses, and social services are scarce.

“Rural Republicans, we see [vouchers] as a slap in the face,” said former Representative Jim Keffer, a Republican from Eastland, in rural central West Texas, who was a top lieutenant of former House speaker and political moderate Joe Strauss. Keffer was one of the Legislature’s most prominent voucher opponents, playing whack-a-mole with pro-voucher bills for 14 years. Eventually, he paid the price for his loyalty to public schools. In 2016, the monied and archconservative Wilks brothers, also from Eastland County, propped up a primary opponent, leading Keffer to bow out of politics. “I always voted against [vouchers], and I suffered the wrath of the tea party or the extremes,” Keffer said.

-

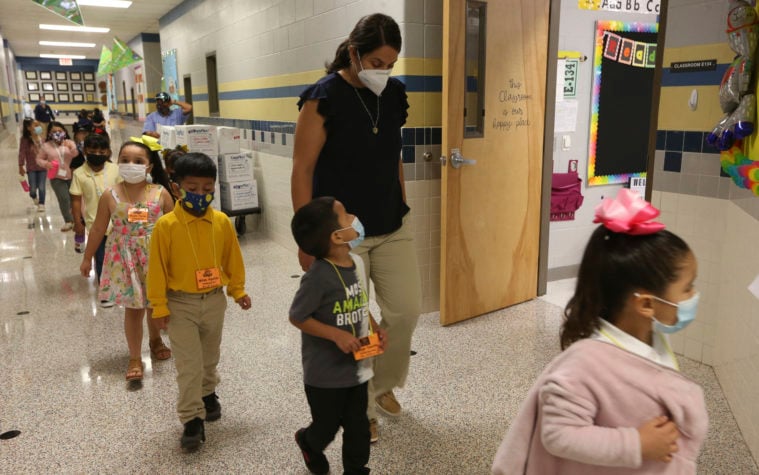

A teacher at Flores-Zapata Elementary in Edinburg leads her class down the hall in August 2021. Credit: Delcia Lopez/The Monitor via AP -

Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick speaks at a school choice rally in 2017. Credit: AP Photo/Eric Gay -

State educators rally to support funding for public schools at the Capitol in March 2019. Credit: AP Photo/Eric Gay

It’s a familiar story in Texas politics, at least for the past decade, when centrist Republicans have been under constant threat. In the Senate, Patrick has led the charge in knocking off moderate senators who sought to protect public schools. Since Patrick took control of the upper chamber in 2014, senators John Carona, Robert Duncan, and Kevin Eltife declined to run for reelection or were trounced by more-conservative candidates. Last year, the kingmakers in Austin redrew Senator Kel Seliger’s district encompassing the Panhandle and West Texas, forcing his retirement. If he wants, Patrick may now have the power to push vouchers hard.

Albert Kauffman, a longtime civil rights litigator specializing in education who teaches at St. Mary’s University, said the current-day fight against public schools is more heated than in the past. “I don’t recall nearly the hate for public school districts the way there is now. There’s nothing quite like today, where ‘schools are centers of wild California philosophies,’” Kauffman said. “And that’s not what public schools are doing. But that’s certainly the impression [opponents] are creating.”

These days, in other words, being tough on schools could be about as fruitful for Republicans as being tough on crime. All you have to do is look at the roiling mobs in Round Rock, Eanes, and Leander to see why.

A week after the incident with the Bible-quoting MAN, Gonzales-Dholakia was at home, pulling the trash bin out to the street when a pickup full of men arrived, hurling threats at her. She fled inside to tell her husband what had happened. The couple added security cameras to their home shortly thereafter.

On another occasion, disgruntled community members carrying holstered bowie knives crowded the entryway to the school board’s meeting room. The atmosphere at yet another meeting became so hostile that members were forced to call a recess. Eventually, Leander ISD brought in police officers for crowd control. The district also implemented a “clear bag policy” to prevent attendees from bringing guns and other weapons inside.

When Gonzales-Dholakia won her seat on the Leander school board, she became the first Latina to do so. The other members were known conservatives deeply ingrained in county politics, though school board candidates run without partisan affiliation. “I was kind of the known progressive on the board,” she said. “When I came in talking about diversity, equity, and inclusion, it was new to Leander.”

In the next school board election, two more progressives were voted onto the board. But it’s hard to make much progress when your meetings frequently devolve into shouting matches. “So many school boards in the suburbs have become these political hot spots, where your board meetings are just chaos,” Gonzales-Dholakia said.

The knife-carrying, threat-making critics at Leander ISD’s school board meetings may have thought their campaign against Gonzales-Dholakia would cause her to back down. If anything, she said, it’s made her more determined to do what’s right for her district. “I’m not going to let them know that they’re scaring me, that they’re intimidating me, because as soon as they think that this is working, then I’ve empowered them to do this—to keep doing this and to do this to other people,” she said.