Documents: CBP Ignored Federal Biologists’ Input on Border Wall

Border security officials visited wildlife preserves in Starr County, then blew off the recommendations of the scientists they brought along.

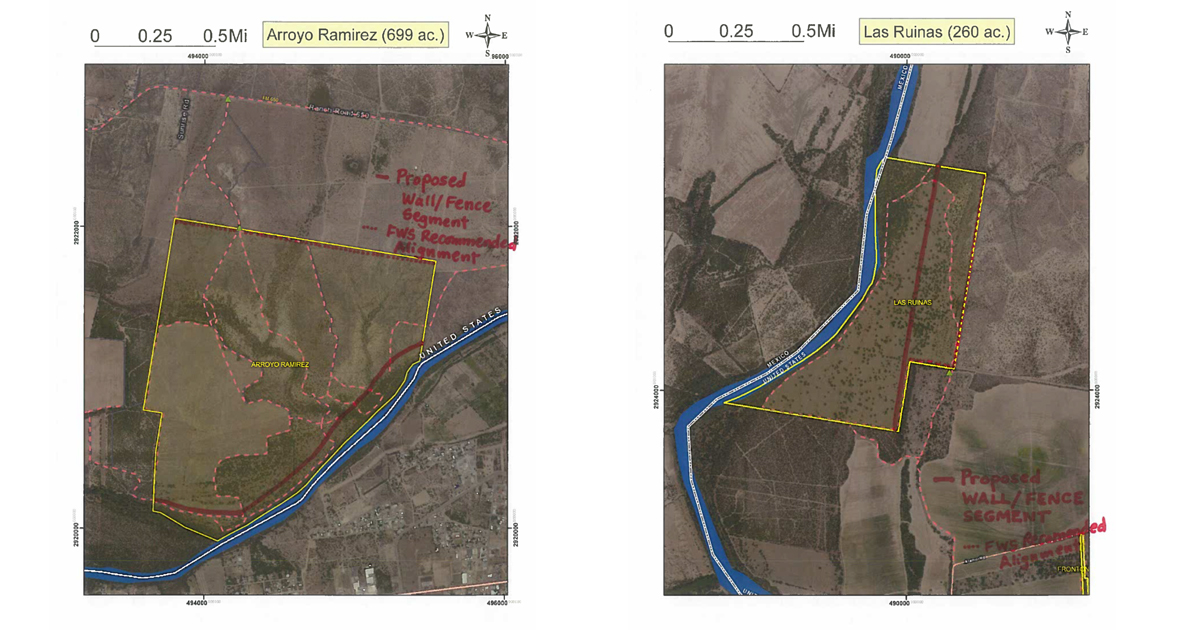

In December 2017, a group of Customs and Border Protection officials met with federal wildlife biologists in McAllen for what CBP billed as a collaborative meeting. Ostensibly, CBP planned to gather scientific input on two stretches of border wall set to slice up riparian nature refuges in neighboring Starr County. After a lunch, the crew traveled west of the town of Roma to visit the preserves: the 256-acre Las Ruinas tract and the 699-acre Arroyo Ramirez tract, home to endangered plant species and an ancient oyster bed. There, according to documents obtained by the Observer, CBP officials did anything but collaborate, instead brushing off the federal scientists’ pleas to modify the wall plans and preserve the refuges. The documents call into question CBP’s claims that it is meaningfully consulting with other federal agencies about the wall.

Bryan Winton, who manages a 98,000-acre system of wildlife preserves in the Rio Grande Valley for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), took meeting notes — which were obtained by the Sierra Club through the Freedom of Information Act and provided to the Observer. During the meeting, Winton suggested CBP move its wall so that it would skirt the edges of the refuges, rather than bisecting them and destroying habitat. “There did not appear to be any interest by … CBP to consider my recommendation,” Winton wrote, adding that the border security officials’ primary motivation seemed to be fitting as “as long a wall segment as possible” on each preserve.

At the Arroyo Ramirez tract, Winton wrote, the proposed path of the wall would “traverse endangered plants … and sensitive arroyos that contain the most valuable habitat on the property,” disrupting the natural drainage system that the ecosystem depends on. CBP officials, he added, had hatched their plans “with no coordination with the landowner — USFWS, and irrespective of the sensitive nature of the areas.” According to records the Observer obtained in January, CBP still plans to proceed with its desired path for the wall through the two tracts, rather than accommodating the scientists’ requests.

For environmental advocates, the December 2017 meeting adds to a growing litany of evidence that the Trump administration is ignoring science. “Once again, we see federal wildlife experts were ignored in the rush to build more wall in South Texas,” said Paul Sánchez-Navarro, senior Texas representative for Defenders of Wildlife, a Washington, D.C., advocacy group. “The Trump administration continues to block [FWS] from actively participating in protecting our natural heritage along the border … to the detriment of wildlife, local landowners and communities.”

In October 2017, officials at the U.S. Department of the Interior, which oversees FWS, stripped federal scientists’ concerns about the wall from a letter to CBP, according to documents obtained by Defenders of Wildlife.

CBP did not respond to a request for comment. But elsewhere, the agency has repeatedly said it is consulting with FWS and developing what it calls “environmental stewardship plans.” CBP officials say they are doing so despite the Homeland Security secretary’s power to waive the federal laws that normally make such consultation mandatory. Last year, the secretary issued such waivers for parts of Hidalgo County, but no waiver has been issued for the Starr County refuge tracts. Congress has funded up to 92 miles of new wall in the Rio Grande Valley, with much of it headed for Starr County.

Reached by phone, Winton, the FWS refuge manager, said he wasn’t at liberty to comment on the 2017 meeting, and an agency spokesperson referred all questions to CBP.