DPS Still Avoiding a Public Hearing on Uvalde Massacre

By delaying the appeal of a fired Texas Ranger, Director Steve McCraw is also postponing a public reckoning.

For the last year, Texas Ranger Christopher Ryan Kindell has been on ice.

Texas Department of Public Safety (DPS) Director Steve McCraw suspended Kindell in September 2022, accusing him of acting incompetently during the horrific attack on Uvalde’s Robb Elementary School earlier that year. After an internal investigation, McCraw followed up in January by firing Kindell over the objection of the ranger’s superiors.

Since then, he’s refused to hear Kindell’s appeal. That means the ranger sits at home drawing his $90,718 annual paycheck without investigating any crimes. From January to June, McCraw fired and promptly heard the appeals of 14 other DPS employees, according to records provided by the agency to the Texas Observer. Kindell was the only employee in that timeframe who hasn’t yet met with McCraw. When asked why McCraw hasn’t met with Kindell, DPS spokesman Travis Considine said the agency doesn’t “have any more information to provide at this time.” Kindell wouldn’t comment.

The long delay “looks awfully weird,” said G. M. Cox, a lecturer in law enforcement management at Sam Houston State University who has served as police chief in several Texas cities. “Why are you postponing? Why are you stalling this?”

By declining to hear Kindell’s appeal, McCraw is also avoiding a public battle with the potential to lift the curtain on the state police’s botched response to the May 24, 2022, massacre that left 19 students and two teachers dead. When a DPS officer is fired, their first recourse is to request a meeting with the director and ask him to reconsider. If McCraw upholds the employee’s firing, they can appeal to the Public Safety Commission. That’s where things are apt to get messy for McCraw.

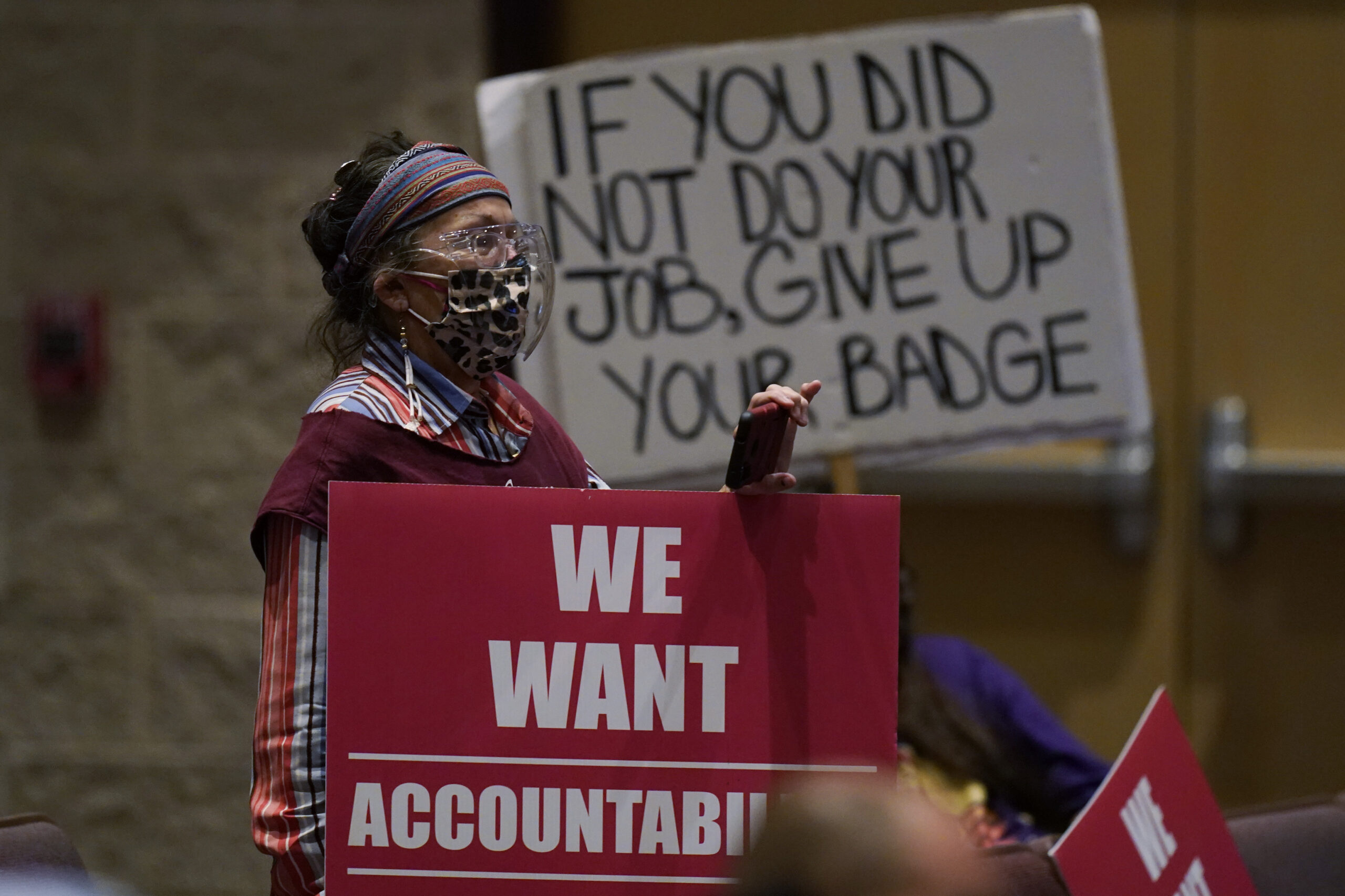

The images of police officers milling around the hallways of Robb Elementary for more than an hour before finally entering the classrooms where students and teachers lay dead or dying have sparked demands for accountability. DPS has been fighting for more than a year to keep the details of its response secret, although countless leaks and a judge’s ruling have undermined that effort. A public hearing before the commission with Kindell and other officials testifying about what happened could bring the transparency that DPS has avoided for the last 16 months.

McCraw has characterized the investigations of seven DPS officials who responded to the shooting—he fired two: Kindell and a sergeant; a trooper resigned—as an example of holding his agency accountable. In his letter dismissing Kindell, McCraw wrote that the Rangers, billed as an elite division of DPS that investigates major crimes in rural counties, have a duty to take “immediate police action” when a crime is committed.

Much of the debate over the police response that day hinges on law enforcement jargon. Former Uvalde Consolidated Independent School District Police Chief Pete Arredondo, on whose shoulders McCraw has placed blame for the disastrous response, has said he thought he was dealing with a “barricaded subject” and didn’t know immediate action would have saved lives. McCraw has said Arredondo—and Kindell—should have known the teenage gunman was an active shooter who needed to be confronted immediately.

“You took no steps to influence the law enforcement response toward an active shooter posture,” McCraw wrote in his letter firing Kindell.

In a report recommending Kindell’s firing that was obtained by the Observer and first reported by Austin’s KXAN, Lt. Patrick Heintz, an investigator for the DPS Office of Inspector General, found that Kindell arrived at Robb Elementary about 50 minutes before officers entered the classroom. During that time, according to the report, Kindell failed to follow the most recent iteration of Advanced Law Enforcement Rapid Response Training, which says: “First responders must put themselves between the shooter and the victims as quickly as possible.” The report acknowledges that Kindell last underwent substantive rapid response training in 2013, though in 2019 he took a four-hour online course about teaching civilians to respond to active shooters, according to records from the Texas A&M Engineering Extension Service’s Criminal Justice Institute.

Heintz also recommended firing Kindell, writing that the ranger had enough information to know he was in an active shooter situation.

“Department policy states Texas Rangers shall make inquiries to determine whether there is a basis for investigation or the prevention of any criminal law,” Heintz wrote. “Due to the exigencies of the situation immediate police action should have been implemented to prevent the criminal acts from occurring.”

In a lengthy rebuttal, Rangers No. 2, Corey Lane, wrote that, based on the facts available to him, Kindell couldn’t have known teachers and children were dying in the classroom. Video of the incident shows Kindell rushing around the campus, looking for a map of the school, meeting with higher-ranking officials, and discussing the situation with the head of the Border Patrol tactical team that eventually breached the door and killed the gunman inside, according to Lane’s memo. Lane acknowledges that Kindell was told about injuries in the classroom, but counters that when the Ranger tried to confirm that information, he was also told at different times that the gunman was dead, was barricaded in an office, or had escaped to the roof. Lane doesn’t claim that anything Kindell did changed the situation that day in Uvalde, but he argues Kindell fulfilled his duties by trying to make sense of the chaotic situation and relay details to his superiors. And the inspector general report never identified any actions Kindell did or didn’t take to warrant his firing, Lane argues.

“There is no evidence to suggest that Kindell was negligent in recognizing or following up on clear information that the scene was an active shooter event,” Lane wrote. “Ranger Kindell was unaware of evidence or information that would have prompted him, or any other Ranger facing the same or similar circumstances, to question the handling of the situation by those who had more knowledge of the incident or who had more tactical experience than Kindell.”

It’s worth noting that the Rangers, whose “how the West was won” mythos is under fire from historians for a past littered with extrajudicial, racist killings, are an insular group within the already insular law enforcement community. They could be circling the wagons when one of their own is at risk. But if Kindell’s firing is justified, why won’t McCraw meet with him?

“The problem is the political side of the equation. They’re trying to control the narrative.”

Kindell is also a defendant along with DPS, McCraw, other DPS officers, and the ex-Uvalde school district police chief in related federal lawsuits filed in Del Rio by family members of those killed. Given the intense scrutiny that the response to Uvalde has drawn to the state police, there are any number of reasons McCraw might want to delay the meeting, said Cox, the Sam Houston State professor. But he said it’s not appropriate to keep an employee on paid suspension indefinitely.

The long delay “tells me that you’re either not sure of your evidence … or they’ve got a problem,” Cox said. “The problem is the political side of the equation. They’re trying to control the narrative.”

In his memo defending Kindell, Lane notes that the ranger spent 20 minutes of his time at Robb Elementary on his phone, much of it speaking with his supervisor. He also points out that Kindell met with two DPS captains and a major before police breached the classroom.

That raises another uncomfortable question for McCraw: If Kindell’s actions warrant firing, what about his superiors’?

Under the Texas Public Information Act, DPS is not required to release information about disciplinary investigations whose allegations are not sustained—in other words, that don’t result in punishment. McCraw told CNN last year that one of the captains on scene was being investigated. But in February, DPS spokesman Considine told reporters that the inspector general’s investigation had been completed. So far, DPS has only acknowledged one firing, that of former Sgt. Juan Maldonado, who was also at the scene. Former Trooper Crimson Elizondo resigned while under investigation and Kindell’s firing has not been finalized. Kindell’s appeal, and a hearing before the Public Safety Commission, could put lieutenants, captains, or even people higher up DPS’s chain of command under the microscope.

Another reason McCraw might be reluctant to let Kindell go before the Public Safety Commission is to avoid tangling with the Rangers and their larger-than-life public image.

Jason Taylor, the Rangers chief, also sent McCraw a memo opposing firing Kindell, who consistently receives high marks on his annual performance reviews. The Rangers’ former Assistant Chief Brian Burzynski, who hired Kindell in 2016, told me: “Ryan is not an incompetent employee. He is anything but incompetent. He is well above average.”

A Public Safety Commission meeting with testimony from current and former top Rangers decrying his decision to fire Kindell could embarrass McCraw, who until last year had deftly handled the increasingly political nature of his position. It would put him at odds with a branch of his own agency, one that many Texans, including the legislators and commissioners who set McCraw’s budget and recently approved his $45,000 raise, still hold in high esteem.

When McCraw fired Kindell in January, Jesse Rizo, whose niece Jackie Cazares died in the Robb Elementary shooting, applauded. Now, Rizo says he’s unhappy the ranger’s case is dragging on and so few DPS officials have been held accountable.

“I wouldn’t necessarily call it per se a cover up, but it’s an injustice,” Rizo said.

Measured against the horrible tragedy that is the Uvalde shooting, the career of one law enforcement officer might be of little consequence. In the context of transparency and accountability for the state police, what happens next to Ranger Kindell carries more weight.