Drag Queens and Churchgoers Find Common Ground in ‘The Gospel of Eureka’

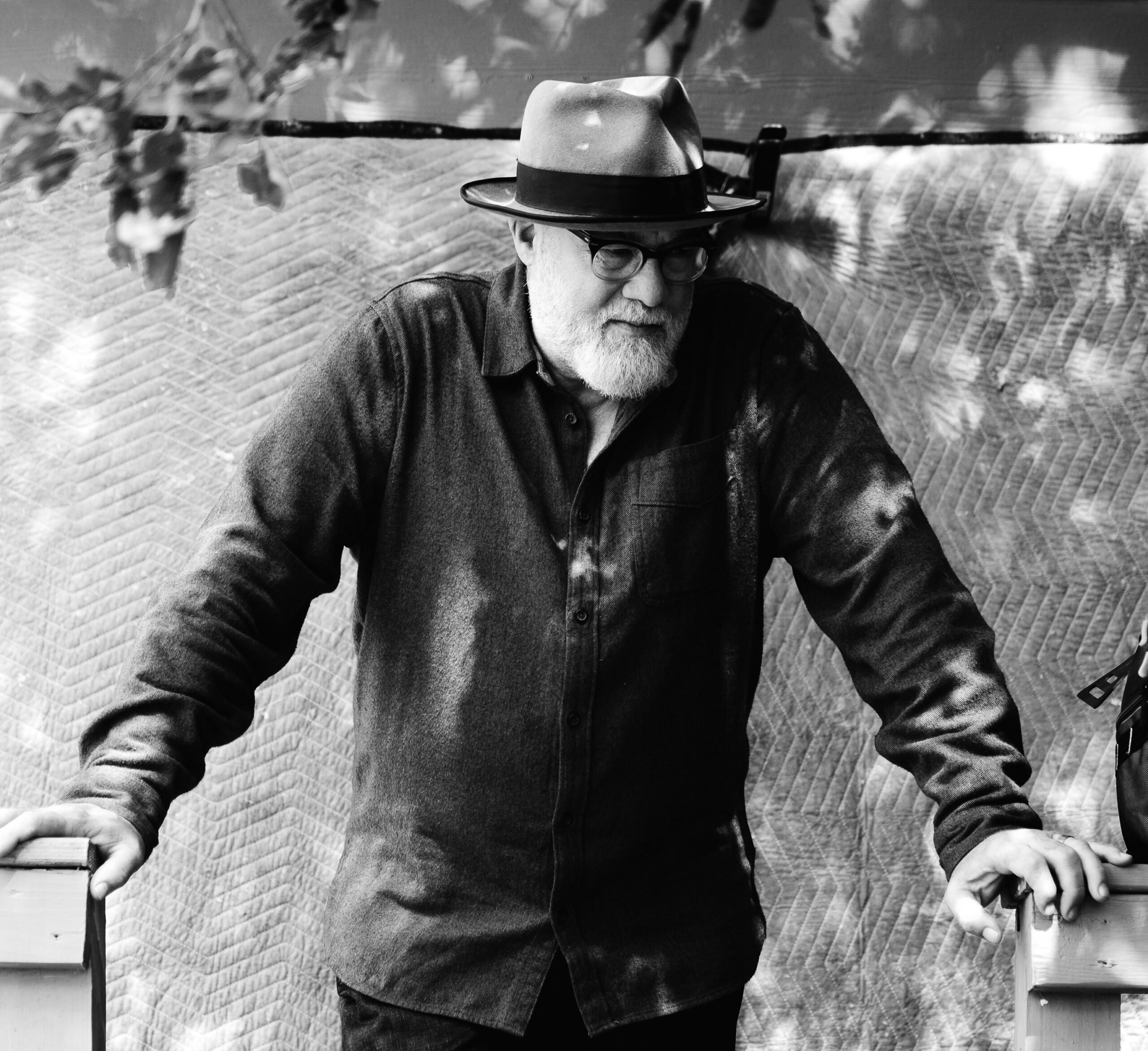

With arms outstretched, the 67-foot-tall mortar Christ of the Ozarks sculpture towers over Eureka Springs, Arkansas, literally and figuratively. For decades, tourists have come to this town of 2,000 to see The Great Passion Play, a dramatic re-enactment of the last days of Christ on an expansive outdoor stage. But Eureka Springs is also home to a distinctly different kind of pageantry: Three times a year, the town hosts Diversity Days, a gay pride festival complete with a parade; a mass wedding; and drag shows, which are held in a local watering hole.

The Gospel of Eureka, directed by Michael Palmieri and Donal Mosher, premiered at SXSW this week. This ebullient movie profiles both constituencies in the runup to a May 2015 election deciding the fate of City Ordinance 2223, meant to protect LGBT people from discrimination. But the film isn’t about a battle for the soul of Eureka Springs. Instead, it’s an optimistic, nuanced portrait of how religion and sexuality intersect in this small Southern town, where two divergent cultures coexist — for the most part — surprisingly peacefully.

Palmieri and Mosher take the audience behind the scenes at both the passion play and the drag bar, Eureka Live Underground. We meet Kent Butler, the actor who portrays Jesus; he matter-of-factly explains how he douses himself with fake blood before the crucifixion and how he clings to the wooden cross. In the Eureka Live dressing room, we watch a drag performer wiggle his false breasts into his dress and listen as another tells how he became an ordained minister and married several couples at the bar.

The film documents a few moments of friction between the conservative Christian community and the gay community. In one scene, a protester at Diversity Days bellows that “Jesus can deliver you from homosexuality.” (Later, a drag queen disagrees, performing Laura Bell Bundy’s “You Can’t Pray the Gay Away” at Eureka Live.) A voter who opposes the nondiscrimination ordinance tells a newspaper reporter that “We’re getting too permissive in this town, and I don’t like it … If you want [gay people], invite them to your house. They’re not welcome in my house.” But for the most part, The Gospel of Eureka depicts the Christian and LGBT communities as a harmonious Venn diagram rather than separate circles.

“God has no problem with me,” explains a trans woman who attends the passion play with her partner. “I don’t see faith as a barrier to being who I am – I see faith as a reason for who I am.” In a Sunday sermon, a local minister cautions against selective enforcement of Levitical law. Those who would condemn homosexuality need to be ready to give up pork, too, as he wryly points out: “Does a rule about homosexuality have anything to do with God’s love and our love for our neighbor?”

Central characters Walter Burrell and Gregory Lee Keating, who own Eureka Live Underground, invite the camera into their home as they smoke, read the Bible and reminisce over photo albums. The two have been married for three decades. Religion often figures in their banter: what it’s like to grow up gay and fundamentalist, whether hell is real. On a visit to the Christ of the Ozarks sculpture, Burrell stares upward and remarks to Keating, “What he’s all about is hope, and that’s why we’re Christians.” It’s clear that those opposing the nondiscrimination ordinance don’t have a monopoly on Christianity in this town.

One of the cleverest sequences cuts back and forth between backstage preparation for the passion play and for the drag show at Eureka Live. In both dressing rooms, men carefully apply makeup before stepping onto a stage and mouthing their lines (the sound for The Great Passion Play is prerecorded). Audiences at both productions seem disinterested as the show begins but become more engaged as the evening progresses. The Great Passion Play and Eureka Live Underground might represent two poles on the political spectrum, but, The Gospel of Eureka seems to ask, are they really that different?

In Eureka Springs, it seems, there’s room for both.

The film’s only substantial shortcoming is that it’s light on information about Eureka Springs beyond the contentious Ordinance 2223 election. The Gospel of Eureka explains how Christ of the Ozarks and The Great Passion Play came to town in the 1960s, but doesn’t answer the more interesting question of how this small Southern village became a gay destination. And the film could say more about the tourist economy of Eureka Springs. The passion play briefly ceased operations in 2013 before being revived by Baptist minister Randall Christy, who alleged the town’s emergence as a gay mecca harmed ticket sales. So, today, which brings more tourist dollars to town: the Christian attractions (the statue, the passion play, an associated Holy Land park) or the gay ones (Diversity Days, the gay bars, the gay-friendly lodging)? We never find out.

Some of those dollars are spent in the Christian T-shirt shop of 30-something artist and father Jayme Brandt. Brandt’s a complex character, embodying the overlap in that Venn diagram: he’s a churchgoer and makes his living selling shirts with slogans like “John 3:16 – true story.” Meanwhile, he campaigns for Ordinance 2223, explaining he finds it repugnant that Christians would form a political movement to codify discrimination. As a child, Brandt learned his father was gay when his parents separated and his mother explained homosexuality as a grave sin, a characterization Brandt eventually rejected. Every time Brandt appears on camera, he speaks with an intensity that suggests his faith inspires far more feelings than he can distill into words. His favorite scripture, he says, is “I believe; help my unbelief.”

Brandt compares the Christian faith of his childhood with the movie E.T. Each involved the discovery of a new reality, an otherworldly phenomenon that became more ephemeral as the years passed. “I think of Elliott as an adult,” Brandt says, furiously sketching the movie’s child protagonist as he talks. “He probably grew up and he never stopped looking up to the sky to find E.T. — he was probably always hoping that he’d be back. But I just imagine that after a while, did he start to wonder, like, ‘Did that even happen?’”

Doubt, hope and longing mingle in Brandt’s analogy, which is worlds away from The Great Passion Play’s straightforward, by-the-book telling of the Christian story. In Eureka Springs, it seems, there’s room for both.