Drinking the Kool-Aid at the Garden of Eden

Searching for community at a North Texas “ecovillage.”

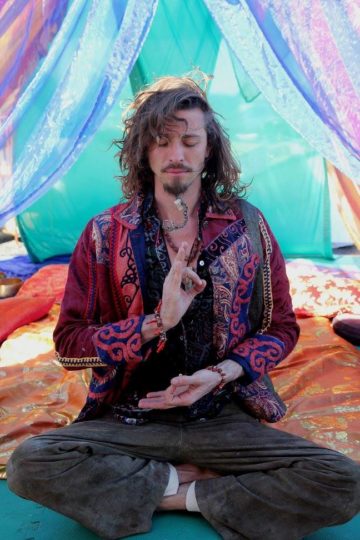

He walked barefoot and topless through the dirt and plants in a white skirt that bounced around his slender calves. His tan, tall muscular body glided through the gardens and his handsome face framed the longest goatee I’d ever seen, braided and intertwined with silver beads. An iPhone was tucked securely in a makeshift pocket as he carried his infant son through my tour of the Garden of Eden.

All the stereotypes I had of communal living came true the day I met Quinn Eaker, and a big part of me wanted to be in all the way. Another part of me wanted to run — fast — for the safety of the suburbs.

“Do you ever eat bugs?” Eaker, 34, asks me.

“I did one time at a museum,” I say. “And it was terrible.”

At the moment, bugs were eating me. Of course a commune that condemns chemicals and emphasizes sustainability wouldn’t have bug repellant with Deet. Today, my bare legs bore the brunt of such natural living.

“How are you not getting bit?” I ask.

“It’s a state of mind,” Eaker says. “Everything is energy.”

Right.

Off a country road in the middle of one of largest metropolitan areas in the country, sits the Garden of Eden, a commune in Kennedale that’s home to 15 to 20 people depending on the day. This “ecovillage” strives to free its residents from the typical westernized culture of siloed living and materialism — a culture that leaves me lonely and stressed out most days, but also happy to have air conditioning and Trader Joe’s.

This mysterious place is just five minutes down the road from a new development with polished $300,000 homes. Their antithesis to such opulence in this rural landscape is hidden behind a high fence; visitors have to ring a bell to enter. The Garden of Eden sits on more than three acres of land, which includes a really cool outdoor cooking space, an Airbnb dwelling, piles of collected trash, rows of gardens, trees, an old hot tub turned into a pool for the kids, a large composting patch, oddly appealing outdoor showers, unappealing but creatively constructed outdoor bathrooms, and a standard 4,000-square-foot house. The house has air conditioning, but Quinn doesn’t use it. He says recirculated air is unhealthy and it costs money to run. I think it’s hot as shit outside and I’d have that baby cranked up no matter how natural I aspired to be.

When I pull up, Shellie Smith opens the gate and tells me where to park.

This beautiful, thin and tan woman owns the property and started the Garden of Eden eight years ago. But she’s lived here for two decades; it’s where she raised her kids with her ex-husband before she started “living in community.”

I can tell Smith, 58, is in love with Eaker by the way she says his name and looks at him. They’ve been together since 2007. But Quinn’s other partner Inok, the mother of his three young children, lives inside the house, too. Their kids laugh gleefully, playing naked behind us as we talk.

“People here don’t drink the Kool-Aid,” Eaker says, laughing. “They drink the water,” which he hands me. The glass is filled with herbs and strawberries of unknown origin. I’m not about to put that in my mouth. At least not yet. I envision being drugged and forced to do some ceremonial dance or — worse — yoga.

I weakened after an hour and couldn’t get enough of that water. It was purified and soaked in herbs grown in the garden. Herbs are just one of the many things grown here; others include kale, spinach, tomatoes, chard, beets and fig trees.

I envision being drugged and forced to do some ceremonial dance or — worse — yoga.

“Life is easier when you help each other,” Smith says. “It’s different from where one person does everything in the normal American life.” She says this commune has been like a laboratory to see what works and what doesn’t. “We live really close to the earth; I don’t ever wear shoes.” And from a number of women I see walking around the house, shirts are also optional.

Here, nobody has outside jobs. Most food is donated, grown or traded. Jobs are assigned that are essential to keeping the place up and running — including a robust social media presence and website. Instead of money, people have time, choice and support.

But hey, even the most kumbaya place in the country needs to pay the bills. And the Garden of Eden is an interesting mix of commercialism and counterculture. It sells a lot of services on its website, including Eaker’s “new paradigm activation and consulting.” The site says, “Quinn is a super catalyst for your evolution!”

Eaker boasts that he hasn’t had a typical job in 17 years. The Colleyville native didn’t finish high school, either, but says he’s spent most of his life reading and studying.

“I’m probably the most well-educated person I’ve ever met,” he says with a straight face. (And humble, as my dad would joke.) Eaker absolutely believes this, and it seems like the rest of the folks here do, too. He walks like an omniscient God purveying his chosen land and planning how to help the rest of society create their own oasis of health and sustainability. Warning: This oasis is probably going to be really hot and full of mosquitoes.

A lot of what Smith says resonates with me. I’m a single mom working a very hard full-time job that I love, but I have to do everything alone.

Eaker’s grand vision (like any Texan entrepreneur, of course, he has one) is to create “ecovillages” across the country that operate with shared responsibilities and benefits, but also have individual houses and income streams — a.k.a. jobs. He says he wants to make sustainability “cool” and show that living that way doesn’t have to mean “a poor peasant life.”

For now, people who want a taste of communal living can pay $33 a year for a basic Garden of Eden “membership.” That gets you the opportunity (after a thorough background check) to see what this style of life is all about. True to his model of living as close to money-free as possible, the membership fee can also be settled through a trade of goods or services. That said, a $250 deposit is required before you can start living at the commune. In the past, visitors have stolen or damaged property.

“We’ve been burned a lot,” says Smith as we sit around a large fire pit after one of the best dinners I’ve ever had.

Smith takes pictures with her phone as Quinn lets his baby crawl over to the fire at a safe distance. “Hi, sweet boy,” he says. The baby smiles and waves a tiny chubby hand near the flame.

A lot of what Smith says resonates with me. I’m a single mom working a very hard full-time job that I love, but I have to do everything alone. Cook. Clean. Groceries. I recently got sick, and my main support system — my dear parents — were out of town. Sure, my friends offered to help out, but my daughter doesn’t know them well enough. She wouldn’t go to bed at their houses and they don’t have lives set up to take her to kindergarten at the crack of dawn. Maybe I’m unconsciously contributing to my own siloed living and loneliness because I’m not doing enough to build community. And building community has to have its own intentionality.

My Fort Worth neighborhood is probably the closest thing to a citified Garden of Eden. Here, Near Southside, Inc., a revitalization-focused nonprofit, has been working to add mixed-use spaces, walkable streets and bike lanes, and other community-driven changes.

But still, homes are separated by fences. Closed front doors. And the prevailing American attitude of respecting privacy and space. Regularly scheduled potluck dinners are hard to come by, and plans have to be made around hectic work schedules and school activities that divide time and make creating lasting relationships tough.

That was the way Smith used to live. She had plenty of money, but it didn’t make her life easier or better, she says. Money gets people to buy more and then they’re trapped into the maintenance of that reality.

The main house at the Garden of Eden is like any other for the most part; it’s got a stocked kitchen and big dining room table. But a large dry erase board hangs on the wall in the kitchen with a list of chores and activities assigned by name to residents. Of course, there’s a room off the kitchen with some curious tent and a strange-looking yoga apparatus. But the real difference is the people. As Eaker’s youngest child crawls around on the floor, he’s swooped up and cared for by another mother of two who’s living there. Inok cooks inside the house while a man grills outside.

My visit to this friendly hippie community lasted about six hours. I was going to spend the night, but couldn’t wait to get back to my daughter at home. The commune reminded me of family, of my divorce, my solitude and my quest to change that. But for me, this was not my Garden of Eden to be. It didn’t feel real. All these barefoot, partially nude, tan and muscular beings meandering through weeds, piles of wood and compost, content with the heat and saved by some higher level of consciousness found through Eaker? I really wanted to believe.

Sitting in an old metal chair near the big bonfire that night, I started talking to Daniel, a 23-year-old from Israel. He was traveling all over the United States and heard about the Garden of Eden from a friend. Just like that, he made plans to stay for two weeks. Fearless and beautiful, this young man with intense brown eyes wrote my name in Hebrew and told me about his family, thoughts on religion, and the loss of a friend. We swooned over the new alt-J album; I wish he’d been older. These happenstance connections are something I hope to cultivate here in Fort Worth — among the sidewalks, early morning commutes, and yes, air conditioning.