‘Dumbfounding’ Ruling on Texas’ Gerrymandered Maps Steers Supreme Court Away From Race

The ruling sets a nearly impossible standard for proving allegations of “discriminatory intent,” the only way left to rein in states that pass racist voting laws.

In a ruling delivered June 25, 2013, Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts declared that it was time to dismantle a key plank of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. “Our country has changed,” he wrote.

On Monday, five years to the day after Roberts’ opinion in Shelby v. Holder gutted the Voting Rights Act, the U.S. Supreme Court sided with Texas in its marathon redistricting fight. The latest ruling upheld nearly all of the state House and congressional maps that, according to a series of lower court findings, sprang from the GOP-dominated Legislature’s desire to curb Texas’ growing minority vote.

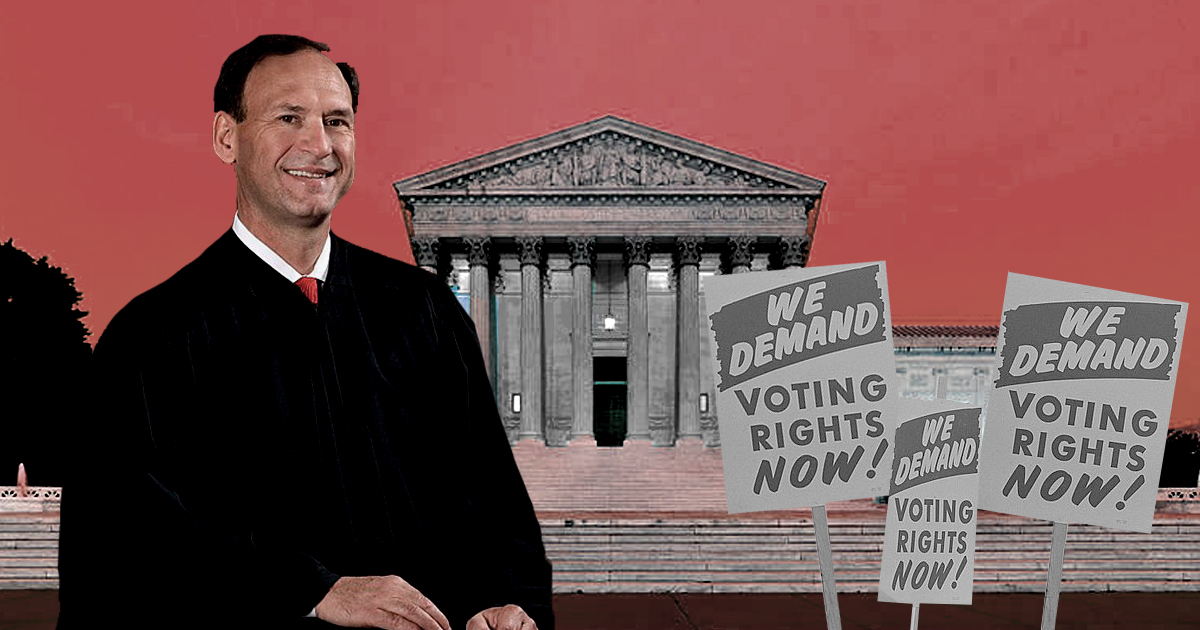

Legal experts say that Monday’s 5-4 ruling, by conservative Justice Samuel Alito, largely confirms civil rights advocates’ fears that the Voting Rights Act, long considered the “crown jewel” of the civil rights movement, has become a shell of its former self under the Roberts court. That’s because the ruling sets a nearly impossible standard for proving allegations of “discriminatory intent,” the only way to rein in states like Texas that perpetuate voting laws that disproportionately harm people of color.

“The court has now basically said that it’s going to be really, really hard to prove that lawmakers intentionally discriminated,” Michael Li, senior counsel at the Brennan Center’s Democracy Program, told the Observer. “It’s sort of like, unless somebody gets up on the floor and says, ‘I despise Latinos and I’m targeting Latinos,’ then you’ll never get there.” Li says the ruling shows the court “is becoming less and less hospitable to claims that are based on race.”

From 1965 until the Supreme Court’s Shelby ruling five years ago, Texas and several other states with a history of race-based discrimination — most of them former members of the Confederacy — needed federal approval, or so-called preclearance, to change voting laws. After Shelby, states that used to be under “preclearance” began curbing early voting hours, eliminating same-day voter registration and rolling out other voting restrictions. Texas soon announced it would implement a voter ID law, which the Legislature passed in 2011 but was blocked under preclearance because it disproportionately harmed black and brown voters.

“The court has now basically said that it’s going to be really, really hard to prove that lawmakers intentionally discriminated.”

Absent the Voting Rights Act’s prophylactic vetting process, Texas’ voter ID case has bounced around the courts for years. A federal judge in Corpus Christi has on two separate occasions ruled that lawmakers passed it with the intent to discriminate based on race. While the Fifth Circuit agreed that the law was discriminatory in effect, the appellate court punted on the finding of racist intent — a finding that, if upheld, could put Texas back under federal scrutiny for changes to voting laws.

On the voter ID law’s most recent trip to the Fifth Circuit, Edith Jones, the most notorious jurist on the famously conservative court, balked at the idea of keeping alive the question of intentional discrimination, insisting on a nearly impossible standard by which you’d have to catch politicians admitting they’re racist before they act that way.

Monday’s Supreme Court ruling on Texas’ gerrymandered maps echoed a version of that thinking, shifting the burden away from the state and directing lower courts to presume “good faith” on the part of lawmakers when deciding whether they intentionally discriminated against voters of color. Writing for Slate yesterday, elections law expert and University of California at Irvine professor Rick Hasen predicted that this section of the court’s ruling will make it “well near impossible for plaintiffs to prove that states have engaged in intentional racial discrimination so as to put those states back under federal supervision.”

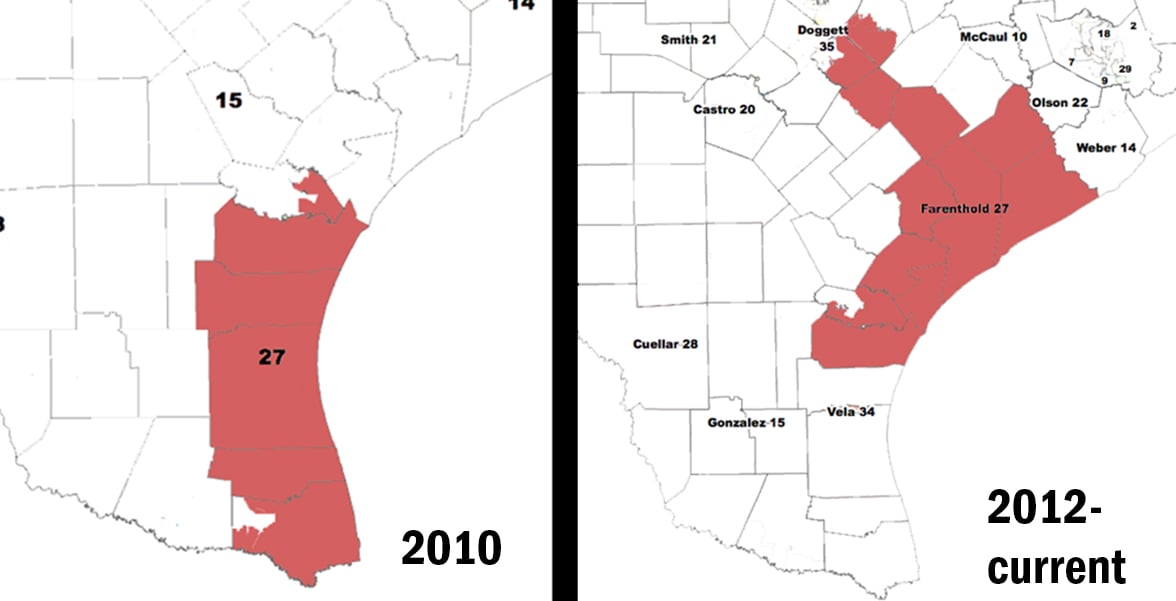

That’s because the record in Texas’ redistricting saga is replete with racism thinly disguised as politics. Like its voter ID law, Texas’ current maps date back to the 2011 legislative session. Texas had gained four new congressional seats because its population had swollen by 4.3 million people over the previous decade, almost all of that growth in minority communities, yet GOP lawmakers drew three of those seats in reliably white, Republican territory. GOP map-drawers that session also largely excluded black and Hispanic lawmakers from the process. They conducted “surgery” in minority districts to remove key businesses, economic engines like sports arenas and, in the case of one Hispanic congressman from San Antonio, even a convention center that bore his father’s name. Meanwhile, Anglo members’ districts were redrawn to include country clubs and the schools their grandchildren attended. Among the other tricks by GOP mapmakers: swapping active Hispanic voters with low-turnout Hispanics to strengthen a district’s Anglo voting power, so that the district still looked good on paper.

“The fundamental right to vote is too precious to be disregarded in this manner.”

The Voting Rights Act’s preclearance tool helped keep the worst parts of that redistricting plan from going into effect, and in 2012 a lower court panel negotiated interim maps, which largely used the Legislature’s 2011 plan as a starting point, so that Texas could keep having elections in the meantime. In 2013, the same year the Supreme Court dismantled the Voting Rights Act in Shelby, Texas lawmakers cut their losses and made those interim maps permanent as a way to kill the lawsuit that civil rights groups had filed over the redistricting plan.

On Monday, the Supreme Court majority decided that making those interim maps permanent sufficiently insulated Texas and its redistricting plan from the allegations of discriminatory intent. Why would lawmakers make the court-ordered maps permanent if they wanted to discriminate?

Of course, as the lower courts have said, you can’t so easily divorce the state’s current maps from the discrimination of the 2011 session — in part because they still feature remarkably gerrymandered districts like former Congressman Blake Farenthold’s Corpus Christi district. In a stinging dissent for the liberal wing of the court, Justice Sonia Sotomayor predicted bleak consequences for voting rights because of Monday’s ruling. Minority voters, she wrote, will continue to be underrepresented with discriminatory maps even as they’re the fastest-growing communities in the state.

“Those voters must return to the polls in 2018 and 2020 with the knowledge that their ability to exercise meaningfully their right to vote has been burdened by the manipulation of district lines specifically designed to target their communities and minimize their political will,” she wrote. “The fundamental right to vote is too precious to be disregarded in this manner.”

Li, who’s closely followed the redistricting case for years, called the court’s decision “dumbfounding.”

“It’s huge, because there’s ample evidence that what went down was Republicans in the Texas Legislature targeted Latinos and African Americans in a way that intentionally reduced their power,” he said. “It gives the state every benefit of the doubt and ignores a lot of that history.”