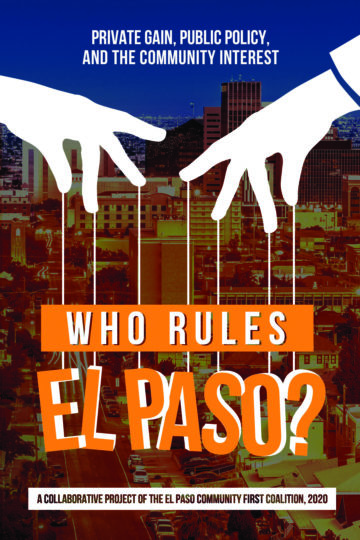

An Incendiary New Book Reveals How Politics in El Paso Are Rigged

Who Rules El Paso? shows how a coterie of rich, primarily white Republicans control local government.

Written by El Paso social justice activists including an attorney, two emeritus professors, and a former county employee, Who Rules El Paso? is the most oblique thing you’ll ever read about native son Beto O’Rourke. The book gives him barely a mention. Still, its data, and the roadmaps it gives readers to pursue their own research, help to illuminate Beto’s political origins. They are troubling, and they are related to the book’s disturbing content.

El Paso, population almost 700,000, is the biggest Texas city on the U.S.-Mexico border. (Its sister city, Juárez, has over a million people). More than 80 percent of El Paso is Latinx. The city is one of America’s poorest. Predictably, it goes blue in presidential elections—as in 2016, when two-thirds of voters favored Hillary Clinton. Candidates elected to Congress also trend Democrat, including Beto.

Local leaders have touted the slogan “El Paso Strong” since a white supremacist fatally shot 22 people, both Mexicans and U.S. citizens, at an El Paso Walmart in August. It was the largest massacre of Latinx people in U.S. history. Locals have since celebrated the fortitude and binationalism of this fronterizo metropolis.

By the El Paso Community First Coalition (Carmen E. Rodríguez, Kathleen Staudt, Oscar J. Martínez, and Rosemary Neill)

Self-published

120 pages; $10

Buy the book here.

But, as Who Rules El Paso? makes clear, post-mortem boosterism hides a dirty secret: The city’s politics are neither robust nor multicultural. Instead, they are weak and racialized. Local government is controlled by a coterie of rich, primarily white Republicans. Most are bankers, real estate investors, and developers. Most abjure elected office but bankroll candidates of more modest means, who doubt they can get elected unless the tycoons fund their campaigns.

The bankrolling buys obeisance. When it comes to decision-making about matters like public land use, property tax rates, and what to include in bond projects, ordinary El Pasoans ask for one thing, but City Council reps and the mayor push for the opposite—and almost always get it. “The system in place in El Paso,” according to the authors, “caters to developers and other business elites, while, with some exceptions, city representatives show little regard for what the citizenry thinks.” In recent years, during public comment at council meetings, salt-of-the-earth residents have railed against proposals to destroy the historic, working-class Duranguito neighborhood to build a glitzy sports arena; to sell beautiful, undeveloped public land that locals use for hiking; and to shrink the city library. In response—as one of the book’s authors, retired political science professor Kathy Staudt, has commented—many council reps and the mayor stared blankly, like zombies. Then, they overrode popular wishes in favor of those held by the rich people who finance their campaigns.

Meanwhile, city officials are shamefully short on ideas to spur economic development, stabilize El Paso’s notoriously high homeowner property taxes, raise persistently low wages, or halt brain drain. Other Texas cities are gaining people; El Paso is losing them, particularly young adults and their children.

The authors of Who Rules El Paso? point out that rich Anglos (along with a few wealthy Mexicans who have binational residency and citizenship) have run El Paso for generations. Until 15 or 20 years ago, many were baldly corrupt. One prominent example is mega-donor Stanley Jobe, who was convicted of bank fraud in 1994. Others who made large campaign contributions offered politicians kickbacks, and they contributed only piddling amounts to local charity.

In the early aughts, a movement of young, well-educated people, including Beto O’Rourke, styled themselves as progressive reformers and began running for office on an anti-corruption, civic-improvement platform. Perhaps naively, they welcomed help from a newcomer group of Anglo Republicans, even richer than the old timers. One was William Sanders, the billionaire real-estate developer father of Amy Sanders, whom Beto married in 2005.

“The system in place in El Paso caters to developers and other business elites, while, with some exceptions, city representatives show little regard for what the citizenry thinks.”

That same year, William Sanders and others in the elite organized a dues-paying, invitation-only club of peers who aimed to remodel El Paso to attract tourists and high-end shoppers to downtown. The group planned to demolish blocks of humble residences that for generations housed poor but striving immigrants. Beto was made a member of the club. He won his first political campaign (for city council) later that year.

The redevelopment plan was denounced by many El Pasoans as classist and racist. In gerrymander style, the neighborhood under threat was tacked into the better-heeled district that Beto represented, and he suffered pushback for supporting the demolition plan. It was eventually scrapped. But Beto’s political career had been launched, with big bucks. Most came from the local oligarchs and their networks. Over half came in quanta of $500, $1,000, and more. Campaign finance data indicate that until the 2005 election, major candidates for El Paso City Council had been collecting about $10,000 in campaign contributions. Beto racked up nearly six times as much. Running again in 2007, he capped donations at $250 per person but still received about the same large amount as in 2005, mostly from affluent donors with Anglo surnames.

Since then it’s become even pricier to win city office in El Paso, and it’s now routine for candidates to get most of their money from contributions of $1,000 and up. Republican Dee Margo fits this pattern. When he successfully ran for mayor in 2017, the oligarchs helped him collect over $250,000—then six times more than an El Paso mayor’s annual pay.

According to Who Rules El Paso? two of Margo’s top 10 contributors were magnates Woody Hunt and Paul Foster. Both are local mega-philanthropists—and conservative sugar daddies. Last year they contributed fortunes to right-wing organizations and PACs. For example, Foster gave $1 million to Engage Texas, a PAC dedicated to registering conservative voters. He contributed almost $754,000 to the Republican federal project Take Back the House. Hunt gave over $400,000 to similar funds, including the Republican National Committee.

In El Paso the two men are widely deemed to be at the top of an “exclusive pyramid,” as the book puts it, of wealthy individuals who “wield disproportionate power and influence over local affairs.” They are major forces behind the zombification at City Hall. It seems no one can escape them. Even earnest local charities and decent Democratic politicians take their money. Texas border communities have low voter turnout rates in local elections, and El Paso’s is among the lowest. This glum fact is likely related to people’s feeling powerless before the oligarchs.

How to replace zombification with democracy? Who Rules El Paso? notes that Austin caps campaign contributions at $400, a possible model for El Paso. El Paso city elections have for years been nonpartisan, making it easy for Republican candidates to obscure their affiliation from voters. Perhaps it’s time to reinstate partisanship. To consider these and other reforms, a no-holds-barred community conversation is needed. Who Rules El Paso? might start it.

READ MORE:

-

What’s in a Name? New lawsuits by transgender people challenge bans on name changes for those convicted of crimes.

-

Jail Deaths in Bexar County Highlight ‘Callous’ Care in Custody: A string of in-custody deaths over the past year point to inadequate treatment for inmates with serious medical conditions.

-

17 Great Books on the Border to Read Instead of ‘American Dirt’: There’s no shortage of talented Latinx writers with all kinds of stories to tell. Let’s make space for them.