A Timely, Enraging Documentary Humanizes the Rape Kit Backlog Crisis

Texas lawmakers have turned to crowdfunding to test rape kits, absent adequate state funding.

In 1996, just days after her 17th birthday, Helena was abducted at knifepoint from a self-service car wash near her home in Los Angeles, held for 10 hours and repeatedly sexually assaulted. When she was finally freed, she says, the man who attacked her kept her driver’s license so he would know where she lived. If she ever reported the crime, he told her, he’d come back and kill her and her family.

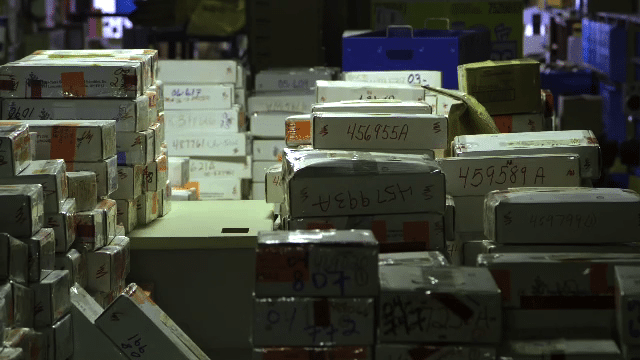

Helena went to the police immediately. She was taken to the hospital, where she spent hours answering detailed questions about the assault and undergoing an invasive evidence collection process to build her rape kit. Then she went home and awaited news of her assailant’s capture — for more than a decade. Like hundreds of thousands of other rape kits caught in a backlog across the country, Helena’s sat untested on a shelf for years.

Helena’s experience is among those highlighted in I Am Evidence, a documentary that powerfully spotlights rape survivors whose traumatic experiences have otherwise been boxed up and stashed away. Now streaming on HBO GO, the film is an enraging story of survivors who are forced to become advocates just to get basic attention on their most harrowing moments. Even then, they learn a system intended to protect is ultimately stacked against them.

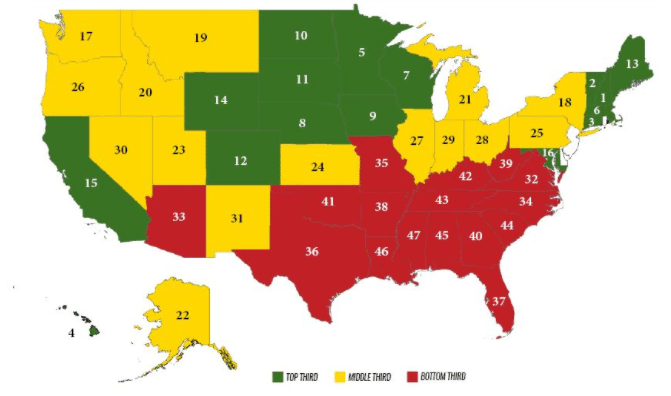

In Texas, about 20,000 backlogged rape kits were identified in 2011. Since then, lawmakers have passed a range of laws and provided new funding to address the backlog. All but about 2,000 of the kits have been processed. But new kits have piled up in the meantime, and there’s no comprehensive total of how many have accumulated. (A new law passed last session requires the Department of Public Safety to implement a tracking system for sexual assault evidence by next year.) With insufficient state funds, Texas lawmakers are now asking private citizens to crowdfund efforts to clear the backlog. A law authored by state Representative Victoria Neave, D-Dallas, last session allows Texans to donate to rape kit testing programs when applying for or renewing a driver’s license. The measure raised nearly $250,000 in its first five months, but a Dallas Morning News editorial in June notes that an estimated $15 million is needed annually to test kits; Neave’s program is expected to raise only about $1 million per year.

Last month, Neave teamed up with former state Senator Wendy Davis to expand crowdfunding efforts. They launched a campaign called “Clear the Kits” that sets up a GoFundMe account for donations outside of the DMV. “Should it be an individual’s responsibility to voluntarily donate to this? I wish it weren’t,” Davis told the Texas Tribune. “But until the state steps up, I think it’s important for those of us who care about this issue to put some resources forward.”

In the meantime, any delay is dangerous. In the years Helena’s kit sat untested, her attacker — later identified as Charles Courtney, a long-distance truck driver who had also been arrested for raping his wife — went on to assault at least one other woman. In 1998, another woman profiled in the film, Amberly, was leaving a grocery store in Fairfield, Ohio, when Courtney abducted her, repeatedly assaulted her and took her driver’s license. It wasn’t until three years later that her rape kit was processed as part of an effort to clear the state’s backlog, and DNA was matched to Courtney, who was convicted.

“If they took this more seriously and believed Helena,” Amberly says, “I would’ve never been raped.”

Cost is commonly cited as the reason for the rape kit backlog, but I Am Evidence paints a more complicated picture of a system in which rape survivors are often disbelieved or simply not prioritized. The film weaves together a courtroom clip in which an attorney’s line of questioning focuses on what the survivor was wearing; police reports that doubt victim’s accounts, including one that reads “this heffer [sic] is trippin”; and a theory held by some detectives that only those who didn’t know their assailant are “righteous victims.”

“I don’t have compassion for the system that made this OK, because the system should be more accountable. The system should be better than a criminal.”

That I Am Evidence comes in the midst of a nationwide reckoning with sexual harassment and assault sets the film up as almost a challenge to lawmakers. We as a country cannot claim to care about stopping sexual assault, yet fail to take the clearest measure to give closure to survivors and prevent future attacks. For years, the film suggests, we haven’t cared; hopefully that can change. Much of the power of I Am Evidence comes from watching survivors confront this idea that the officials they expected to protect them have other priorities.

“I can’t understand why I was so unimportant,” a tearful Helena says, describing her years living in fear that her assailant would find her again. “I’m not angry at Charles Courtney; I’ve long moved past that feeling. Terrible things happen to people, violence is learned. I have compassion for him. I don’t have compassion for the system that made this OK, because the system should be more accountable. The system should be better than a criminal.”