by Rebecca Grant

January 22, 2019

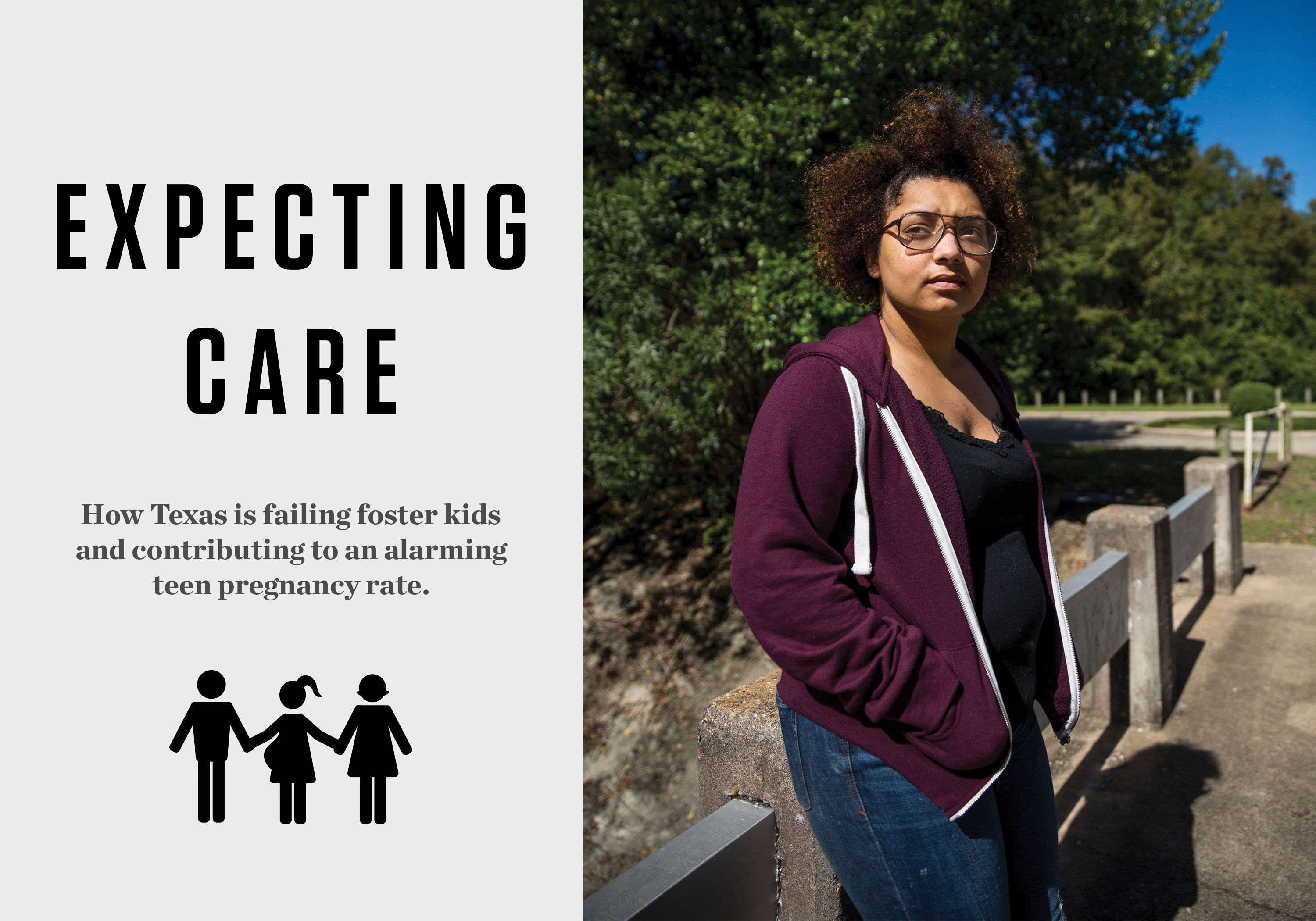

When Arianna walked into a church basement in Austin to take a free pregnancy test, she thought of it as a lark, a way to kill time during the long, dull days of life as a street kid. About a month before, she had run away from the Austin Oaks mental health facility and was now living with her boyfriend in an alley near the Texas Capitol. The idea of being pregnant was laughable.

“It was just laughs and giggles while we were waiting in line,” she said.

Afterward, she remembers one of the volunteers, an older woman, pulling her aside and telling her she was pregnant. Arianna, who asked that her last name not be used, said her first reaction was to “freak out.” Caught between denial and panic, she was saddened by the realization that she was no longer a kid. At the same time, she was exhilarated.

“The moment you find out you’re pregnant, you don’t feel lonely, you don’t feel sad, you don’t feel angry,” she said. “You feel loved already.”

Arianna was 16. Three years earlier, Child Protective Services had removed her from her great-grandmother’s home and put her into Texas’ deeply troubled foster-care system. As unstable as living with her relatives had been, foster care was also chaotic and traumatic. Feeling as if no one was on her side, she ran away and spent about a month on the street before CPS learned where she was. Her caseworker drove across the state to pick her up and return her to the system. When she gave birth to her son, she was living at The Treehouse Center, a residential treatment center in Conroe. Arianna wasn’t ready to be a parent — she didn’t have a degree, a home or much of a plan for her future — but she knew she wanted to create a better life for her child. She was a devoted mom, reading books about parenting, playing games with her son and dressing him in nice clothes. Less than a year after her son was born, Arianna found out she was pregnant with another baby, a daughter.

“All my friends that I was in placements with — every single one — either has a kid or is pregnant right now.”

Arianna’s story is startlingly common. Last year, the state revealed for the first time how many teen parents are in the care of the Department of Family and Protective Services (DFPS). According to the most recent figures, 550 girls out of 5,226, or almost 11 percent, were either pregnant or parenting.

Girls aged 13 to 17 in foster care are nearly five times as likely as their peers to become pregnant, according to an April report by the nonprofit Texans Care for Children. For older teens, the risk is even higher: More than half of teen girls who age out or extend their time in care will become pregnant before they turn 20. The report concluded that the state’s efforts to prevent pregnancy among foster care youth are “inadequate” and that Texas is “falling short of fulfilling its responsibility to these children.”

From heavy caseworker loads to a shortage of foster homes, the problems with the Texas foster care system are well-documented. Experts say these widespread, systemic issues make it harder to prevent teen pregnancy. For instance, if a foster child sees her caseworker only once a month, she’s unlikely to form the kind of close relationship that would make a conversation about sex or contraception seem possible. Frequent moves among foster care homes can have a similar effect, as a steady stream of new guardians prevents kids from building trust.

But perhaps the most troubling and insidious dimension of the teen pregnancy problem in foster care is a culture of silence and stigma surrounding sex. Judges, foster parents, caseworkers and academics interviewed for this story described a system that discourages adults from sharing information with foster youth that would help them avoid unplanned pregnancies. The influence of the religious right is so strong that some foster parents fear repercussions for offering even cursory sex education. Making matters worse, once girls become parents, the state is ill-equipped to provide support.

“We’ve taken kids who are already vulnerable … and instead of protecting those children, we’ve set up a system where they are actually now more vulnerable,” said Monica Faulkner, a professor at the University of Texas at Austin’s School of Social Work and a former case manager. “It is just outrageous.”

For girls like Arianna and the eight other current and former foster youth who were interviewed for this article, teen pregnancies may have been unplanned, but they were, in some ways, inevitable.

“All my friends that I was in placements with — every single one — either has a kid or is pregnant right now,” Arianna said.

Arianna is goofy, energetic and always in motion. When we meet at an IHOP in Conroe, she orders rainbow-sprinkle waffles and starts to tell her story. Her mother struggled with alcoholism and a series of tumultuous romantic relationships; her dad wasn’t in the picture. Arianna spent most of her childhood living with her great-grandmother near Beaumont. As Arianna entered her teens, she began getting in fights at school, and her great-grandmother, who was experiencing the onset of dementia, couldn’t care for her anymore.

Arianna’s path through the foster care system was labyrinthine. From age 13 to 18, she bounced from emergency shelters to foster homes, from residential treatment centers to mental health facilities. She doesn’t remember any adult talking to her about sex in a meaningful way.

“Honestly, I didn’t understand the vagina until I had sex for the first time [at 15],” she said.

In theory, Arianna could have gotten sex ed in school, but more than 83 percent of Texas school districts teach abstinence-only or no sex education at all, according to research from the Texas Freedom Network Education Fund. Another opportunity would have been through Preparation for Adult Living (PAL), a state program that teaches life skills, such as coping with stress, managing finances and taking care of one’s health, to foster youth 16 and older. The PAL curriculum varies wildly from region to region: While a teen in Austin may get a comprehensive overview of contraceptive options, a teen in Amarillo may participate in PEARLS, a Bible-based program “designed to help teen girls choose a lifestyle of purity despite society’s pressures.”

“In Texas, we have this cultural belief that when you are talking about sex, someone else will do it better, or that teen is not going to have sex. That cultural view affects the policies and parents’ ability to talk about it.”

Like Arianna, 21-year-old Kathryn, who also asked that her last name not be published, can’t remember ever being offered sex ed in school. She did receive sex ed through the PAL program, but it was too little, too late. For one thing, Kathryn said, she was already sexually active when she entered foster care at age 15, and she’s not alone. In 2009, about 20 percent of foster care youth reported having sex at age 13 or younger, compared to 8 percent of a general sample of teens, according to the most recent National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being. Kathryn also said the PAL classes didn’t present information in a way that resonated with her. The instructors seemed most interested in scaring her and her friends into abstinence until marriage, which made them less inclined to listen.

“We saw some nasty stuff — they would show us pictures of STDs,” she said. “They made it all look bad. In the videos it said, ‘Abstinence is the way.’”

During Kathryn’s first year in foster care, she spent time in emergency shelters, foster homes and mental health facilities. When she was 16, she moved to New Life Children’s Center in Canyon Lake, an all-girls residential facility that she loved. After a year there, she moved with her older sister to a small town near San Marcos. About four months later, at age 17, she unexpectedly got pregnant.

“I didn’t think I was going to get pregnant because I had been irresponsible before and it didn’t happen,” Kathryn said.

Like so many of her peers in foster care, Kathryn had an unstable and traumatic childhood. Her mother abused drugs, and CPS was a constant presence in her family’s life. But being taken away from her family and placed in foster care was also heartbreaking.

“I cried every day,” Kathryn said about her first placement. “I never quit crying.”

It’s hard to overstate the profound and pervasive impact that trauma has on kids under CPS care. They come into the system already dealing with the underlying problems that landed them there in the first place. Then, all too often, they are further traumatized by a system in which “rape, abuse, psychotropic medication and instability are the norm,” as Judge Janis Jack wrote in a verdict on a class-action lawsuit against the state in 2015, which argued that Texas was failing to care for and protect kids in the foster care system.

Foster kids’ lives are steeped in a chaos that shapes the opportunities available to them and the decisions they make. Kate Murphy, an author of the Texans Care for Children report, said many girls in the system are searching for attention, affection, validation and love, and sex can be a way to get that. The more trauma a child has endured, the more likely they are to engage in high-risk sexual behavior, such as sex at an early age, sex with multiple partners or failing to use protection, according to research from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Kaiser Permanente. Each “adverse childhood experience” or ACE, incrementally increases the risk of teen pregnancy.

“People are scared because of the state we live in and the messages we have. And we have people who will literally go after you. I think it’s a legitimate fear.”

All foster care youth have at least one ACE: the trauma that landed them in CPS custody. That means they’re at a higher risk of teen pregnancy from the start — a risk the state doesn’t do enough to mitigate, Faulkner said.

“Sex is this big thing that nobody talks about that drives me insane,” she said.

If adults don’t bring it up, kids certainly won’t. Both Arianna and Kathryn said there were few, if any, adults in their lives they could talk to openly about intimate subjects. As a result, they relied on their peers for information. Arianna remembered hearing from her cousins that she could only get pregnant on certain days of the month. This wasn’t inaccurate, but it was misleading to a teenager without a strong grasp of how her body worked.

Morgan Miles saw firsthand how poorly informed foster kids were when she worked as a sex educator at an emergency shelter in Austin. She said the stigma around sex means everybody drops the ball — foster guardians, caseworkers, health-care professionals, teachers — because they assume, or hope, that someone else is addressing the issue.

“In Texas, we have this cultural belief that when you are talking about sex, someone else will do it better, or that teen is not going to have sex,” said Miles. “That cultural view affects the policies and parents’ ability to talk about it.”

Adults in the system who do make sex ed a priority can face repercussions. Six child-welfare professionals described to the Observer a prevailing culture of fear that they could be fired, delicensed, cited or sued for discussing sex or facilitating access to birth control or abortion.

“I know when I was a caseworker, I was so scared to talk about birth control and stuff with the kids,” said Mary Green, who now manages a youth center in Houston. “It’s scary, as the adult, to talk about with someone under 18 because of the rules, the laws.”

Kids, too, don’t know what they can and cannot say, particularly if they are in a religious foster home or facility. Religion plays a big role in the Texas foster care system. Many child-placing agencies have religious affiliations. And in an effort to address the severe shortage of foster care beds, Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick has urged faith-based organizations to recruit foster and adoptive parents, with a conspicuous focus on Catholics and evangelical Christians.

“The state is doing nothing. … It’s the belief that sex only occurs when people are married, period. And that is such a ’30s, ’40s, ’50s mentality.”

A law passed by the Texas Legislature in 2017 makes it easier for faith-based agencies to invoke “sincerely held religious beliefs” in refusing to provide services. Agencies and foster parents can decline to make referrals for contraception, turn away LGBTQ parents who want to foster or adopt, and even choose not to immunize kids. Critics of the bill said it was a naked attempt to give conservative Christians the right to discriminate.

“People are scared because of the state we live in and the messages we have,” Faulkner said. “And we have people who will literally go after you. I think it’s a legitimate fear.”

Kathleen and James Burnside, who fostered teenage girls in Austin for a decade, can testify to the power of the taboo. After one of their foster daughters ran away for a few days, she told them she’d had unprotected sex with multiple men. Alarmed, they went to the pharmacy for emergency contraception, but after DFPS found out, the state cited the Burnsides’ child-placing agency. (Citations include small fines, and can also put an agency at risk of losing its contract with the state.) The agency said the Burnsides violated the rules by not first obtaining a prescription, even though the matter was time-sensitive. But Kathleen believes the real issue was the nature of the medication.

“There was a freak-out because we’re in Texas, and emergency contraception is very controversial here,” said Kathleen.

Child-placing agencies are supposed to have a plan in place to teach kids 13 and older about healthy relationships, sexually transmitted infections and human reproduction, according to DFPS’ minimum standards. However, of 126 agencies surveyed by Texans Care for Children, just 38 percent had a specific plan in place.

The Burnsides were surprised by the total absence of sexual health in the trainings they underwent as foster parents. Kathleen said the training was one-size-fits-all, the same for people fostering infants as for those fostering teens. They learned how to administer psychotropic medications and restrain violent kids, but reproductive health was not part of the curriculum.

“These girls are going to get pregnant if you don’t watch it, and have so many problems,” Kathleen said. They are “in a shit-ton of pain. They are not good at managing their lives.” She and her husband talked about sex openly with the girls they fostered. “Our attitude was, ‘We can’t stop you from having sex, so … please get on birth control.’”

Not all foster parents are as open, said Ashley, a 24-year-old who lived with the Burnsides from age 13 to 17. Before Ashley arrived at their home as a young teenager, she had spent time at a foster home that was deeply religious and seemed unwelcoming toward any discussion of sex or contraception.

“I went to this really weird religious family, where we could only watch religious movies and listen to religious music and I had to go to church,” Ashley said. “And I’m not a churchgoer at all.”

After that experience, Ashley told the child-placing agency that she wanted a foster home that was artsy and cultured, with books around the house, and she was placed with the Burnsides. Ashley said that because she felt safe with the Burnsides, she trusted they wouldn’t judge her or kick her out for being sexually active.

There are no simple solutions to the problem of teen pregnancy in the foster care system, but Judge Darlene Byrne, who presides over the 126th Civil District Court in Travis County, highlighted greater accountability as an important step. Byrne, who has overseen the county’s foster care cases since 2007, said there needs to be better tracking of individual foster teens’ sexual health. For example, Byrne would like to be able to check her electronic docket and see who is pregnant or parenting, or who hasn’t received sex ed. Reproductive health shouldn’t be slipping through the cracks.

“A child is only going to give you so many opportunities,” she said. “We’ve all got to be ready.”

Byrne said she generally knew the “horrific numbers” for teen pregnancy in Texas, but witnessing a steady stream of pregnant foster teens in her courtroom made her realize the severity of the problem. Last year, she said, she had a 17-year-old girl on her docket who was expecting her third baby. Byrne described Texas as being in the “dark ages” when it comes to state policy about teen pregnancy.

“The parent is the state of Texas,” Byrne said. But “the state is doing nothing. … It’s the belief that sex only occurs when people are married, period. And that is such a ’30s, ’40s, ’50s mentality.”

The state has taken some steps to address teen pregnancy in the foster care system, such as incorporating reproductive health into its minimum standards and developing the PAL curriculum. Collecting data on the total number of pregnant and parenting foster youth also helps provide insight into the scale of the problem. The report from Texans Care for Children acknowledged these steps, but found that “well-intentioned efforts have suffered from a lack of focus and follow through.”

Shortly after the report was released, DFPS Commissioner Hank Whitman said in a statement that it was “based on misleading conclusions and flawed methodology.” He emphasized that foster care does not cause teen pregnancy and that the agency “continues to work to improve outcomes for all children in our care.”

Arianna’s mother said the state had simply failed to do its job.

“She was 16 years old,” she said by phone. “Where were you when my child was out having sex and getting pregnant? I wasn’t so much mad at Arianna. You’re supposed to be supervising these children. You took my kids from me because you said I wasn’t supervising them adequately, and she got pregnant on y’all’s watch.”

Updated: The story has been updated with comment from DFPS.

This article was reported in partnership with the Investigative Fund at the Nation Institute.