How the Expiration of Austin’s Police Union Contract Could be a Rare Opportunity for Reform

Austin is the latest city where activists have sought police reform by targeting collective bargaining agreements.

For a manual on police union negotiations, Ron DeLord’s early work makes for an entertaining read. The former head of the Combined Law Enforcement Association of Texas (CLEAT) for two decades, DeLord has published acerbic how-to guides for police union bosses on securing generous benefits and pay raises for cops, complete with insult-laden passages calling city officials cockroaches and reporters lying drunks.

But recently DeLord has struck a more defensive tone. “When did citizens stop coming to the aid of officers and become only interested in videoing the officer fighting for their life?” he writes in the recently published Law Enforcement, Police Unions and the Future. The book waxes nostalgic for the good old days when running afoul of the local law enforcement union could ruin political careers, and it offers tips on dealing with controversial cases, such as digging up and publicizing dirt on people injured or killed by cops.

DeLord’s book also warns union leaders to be prepared for what he calls “the most dramatic police reform movement in the United States in more than a hundred years.” He seems to accept that changes are inevitable, advising unions to get what they can: “Always bend before you break.”

DeLord is certainly in a position to understand how much has changed for police unions. This year, he was the lead negotiator for the Austin Police Association as it brokered the latest version of its five-year contract with the city. While police union collective bargaining agreements outline pay raises and benefits for officers, in some cities, like Austin, they also dictate everything from disciplinary rules to oversight and accountability. Austin inked the contract 17 years ago, when the police union agreed to a kind of oversight that was virtually unheard of in other Texas police departments, including an independent, city-appointed police monitor and a hand-picked panel of citizens tasked with reviewing internal investigations into police killings and allegations of officer misconduct. In exchange, Austin cops became the highest paid in the state.

But as DeLord writes in his book, times have changed. This year, as Austin and its police union negotiated a new contract, a coalition of local, state and national watchdog groups demanded that the city radically alter or scrap its collective bargaining agreement for cops. Sam Sinyangwe, a policy analyst and data-cruncher with Campaign Zero, a kind of research arm of the Black Lives Matter movement, calls the contract that Austin has operated under for nearly two decades “one of the worst we’ve seen in the entire country in terms of police accountability” due to sections that ensure a toothless system of citizen oversight and protections for cops accused of misconduct.

“Citizen oversight is still basically subject to whatever good, bad or indifferent investigation internal affairs conducts.”

Austin is just the latest city where activists have sought to reform a police department by targeting its union’s collective bargaining agreement. In cities where police unions are still juggernauts of local politics, such as San Antonio, those efforts have failed. But in Texas’ liberal-leaning capital city, the union appears to have been forced into taking DeLord’s “bend before you break” approach.

Austin Police Association president Ken Casaday argues his union has made concessions that would simply not have happened in other cities. For example, the union ultimately budged on a reform that would allow Austin’s independent police monitor to investigate anonymous complaints against cops. “We’ve got the most oversight of any police department in the state of Texas,” Casaday told the Observer.

Despite what Casaday calls significant changes to the proposed contract, which could go before a City Council vote as early as next week, activists have urged Austin leaders to let the union’s collective bargaining agreement die. That would drag the city back to baseline standards outlined in state law and kill off the city’s current systems of police oversight, including the police monitor and citizen review panel.

Activists argue that without fundamental changes that the union wouldn’t accept in contract negotiations, the new proposal would lock Austin into a flawed system of police oversight that citizens will be powerless to change for the next five years. They insist that what progress has been made in the latest contract proposal is only low-hanging fruit and not worth the estimated $82.5 million it will cost the city over the next five years in pay raises and extra benefits. The activists insist the scorched-earth approach would free the city to build a new system of accountability from the ground up amid the roaring national discussion around community policing.

“We’ve seen what’s supposedly the best oversight that money can buy, and it’s not worth it,” said Chas Moore with the Austin Justice Coalition, a grassroots group that pushes for police reform.

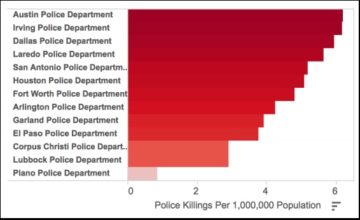

Moore says that Austin police currently have oversight without accountability. He points to a presentation that Campaign Zero recently made to community groups around the city, which shows that Austin cops kill more people per capita than any other large Texas city, and that black residents make up 8 percent of Austin’s population but account for 12 percent of APD traffic stops and half of unarmed people shot by Austin cops in recent years. (APD didn’t respond to the Observer’s questions about its citizen oversight process or the cases mentioned in this story.)

Unlike other cities with strong police union contracts, Austin may be unusually situated for change. In 2014, voters replaced the six at-large city council seats with 10 single-member districts, a change that weakened traditional special interests and ushered in a more progressive set of council members. Greg Casar, one of the new members, suspects that the police union simply has less power to make or break individual City Council candidates now. Casar says that regardless of what happens with the contract proposal, the debate around it has already led to change, including an audit of how APD has responded to recommendations from the city’s citizen review panel.

https://www.facebook.com/GregorioCasar/photos/a.623578621062723.1073741828.621003034653615/1595208053899770/?type=3&theater

Casar knelt with activists protesting police brutality at the start of a city meeting in October and says he plans to vote against the proposed agreement, despite concessions made by the union. “Many of these reforms are common sense and should be baseline expectations for any police department,” Casar said, “and they’re still not enough.”

Activists also argue that some of the proposed reforms are either useless or half-baked. For instance, the union agreed to adjust a rule that APD only has 180 days from the date of any alleged misconduct to investigate and discipline officers. Under that rule, the officer caught on dash-cam video body-slamming Breaion King, a young black elementary school teacher, to the pavement during a 2015 traffic stop wasn’t investigated because higher-ups didn’t know about the incident until after the 180-day window had passed. Even though then-Austin Police Chief Art Acevedo said he was “sickened and saddened” by the arrest and publicly apologized to King, he couldn’t do anything about it.

https://www.facebook.com/grassrootsleadership.page/videos/1764573770238438/

The union eventually agreed to tweak the rule so that the 180-day clock starts running once APD higher-ups learn of allegations that could fit the description of a criminal charge. Still, under the newly proposed version of that rule, it appears the assisting white officer who hauled King to jail and lectured her on how people are afraid of African Americans because of their “violent tendencies” wouldn’t have been investigated or disciplined — because while that may be appalling and hint at larger problems at the department, it’s not a crime. “The rule would still protect that officer,” Moore said.

An even larger problem with extending the contract, according to Kathy Mitchell with the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition, is that it does little to fix what she calls APD’s broken system of citizen oversight. Even with upgrades the union agreed to last month, the department’s citizen oversight panel would only be allowed to review the work of internal affairs investigators and then make recommendations that police officials are free to ignore. “Citizen oversight is still basically subject to whatever good, bad or indifferent investigation internal affairs conducts,” Mitchell told the Observer. “Citizen watchdogs still don’t get subpoena power, access to evidence or the ability to question witnesses when officers are accused of misconduct.”

Austin civil rights attorney Jeff Edwards says the February 2016 death of unarmed, naked 17-year-old David Joseph shows both the limits of Austin’s current system of police oversight and how the union can still flex its muscle in the aftermath of headline-grabbing cases.

In a letter to then-chief Acevedo, who left last year when he was hired to lead the Houston Police Department, Austin’s citizen review panel called Joseph’s death “evidence of systemic problems with APD’s use of force practices and tactics” and urged police to change the way they respond to mentally disturbed people. The panel suggested other ways to prevent similar tragedies, such as transferring a 10-year instructor out of the department’s training academy because he, like Geoffrey Freeman, the officer who shot the unarmed 17-year-old, saw nothing wrong with Joseph’s killing. Though the panel has made similar findings and suggestions in other cases, including other mental health calls that ended with cops killing people, a recent Texas Criminal Justice Coalition report concludes that Austin police have largely ignored the advice. Edwards, who helped Joseph’s family negotiate a $3.5 million settlement with the city of Austin this year, says the system of police oversight “borders on worthless.”

The Austin police union scolded Acevedo for standing with activists at a press conference to promise a thorough and quick investigation of Joseph’s death, and then filed a complaint against the chief for discussing the shooting with cadet classes before the department had wrapped its internal investigation, resulting in a city reprimand for insubordination that docked Acevedo four days pay. The chief ultimately fired Freeman, but the officer’s lawyers secured him a $35,000 settlement and a “general discharge,” which means he can join another police department. Such run-ins have evidently left Acevedo with a jaundiced view of the Austin police union.

“I think the union leadership here [in Houston] is a little bit more sophisticated than the one I found myself dealing with in Austin,” Acevedo told the Observer in a recent interview. “That’s why they’re much more successful, and that’s why they have much more sway politically. You cannot have a mindset that cops can do no wrong; I don’t know of any firing in Austin where the union said, ‘OK, that was appropriate.’”

If City Council listens to activists and lets the contract expire at the end of the year, Mitchell says it would force Austin to confront police accountability. “This city has not had a significant dialogue on how we should be doing police oversight in 20 years,” she told the Observer. “Every other time the city has renegotiated this contract, there just wasn’t this big public debate happening around these issues. Five years ago, the world was a different place. This is our first post-Ferguson round of contract negotiations.”