“I Was Just A Junkie”

This is the third story in an Observer series investigating how widespread use of flawed arson science wrongly convicted dozens, perhaps hundreds, of innocent people in Texas. You can read the previous stories in the series here and here.

She warned him not to go alone. It was a Wednesday morning in late August, and Alejandra Quintanilla was driving to the courthouse in downtown Houston. Sitting next to her, in the passenger seat, was her older brother, Alfredo Guardiola. He had been subpoenaed to appear before a grand jury to testify about one of Houston’s most notorious house fires. Four people had died despite the rescue efforts of Guardiola and several other men who had rushed from neighboring houses to help. He wasn’t a suspect. Prosecutors said they just wanted him to recount for the grand jury what he saw the night of the fire. Still, the subpoena made Quintanilla nervous. Her brother was a gentle man and a heroin addict, and she feared the police would take advantage of him. Tales of coerced confessions were well-known in Houston’s Latino community. As they drove downtown that morning, she tried to convince him to take a lawyer along. But Guardiola saw nothing to worry about. He had nothing to hide, he said. There was no reason to be suspicious. She dropped him outside the courthouse a little before 9 a.m. That was the last time she’s ever seen him outside prison.

When Guardiola walked into the courthouse that morning, he had already spoken with police and fire investigators at least a half-dozen times since the fire. His account hadn’t changed: He had been hanging out at a friend’s house in Denver Harbor, a mostly Latino neighborhood on Houston’s east side, on May 11, 1989. A little after midnight, he heard shouting. He went to the window and saw a nearby house on fire. He bolted outside and jumped two fences. When he reached the front of the burning house, he could hear the Gonzales family, the parents and their three children inside crying for help. Guardiola and two other men tried to bust through the front door and to crack the large front window but couldn’t break either. The Gonzales family had barricaded the front door with plywood and encased the windows in metal bars after they’d been terrorized by burglaries of their home. Guardiola could see the mother, Elizabeth Gonzales, through the large front window but couldn’t reach her. Flames sprang from the windows and roof. After a few minutes, the rooms darkened with smoke, and he no longer saw anyone inside. He later learned that one member of the family survived—9-year-old Joe Louis, who said his father had broken a window with a shotgun and squeezed him out between the bars. But his parents and two young siblings died. The fire haunted Guardiola. He often thought about the image of Elizabeth Gonzales trapped behind the window, screaming.

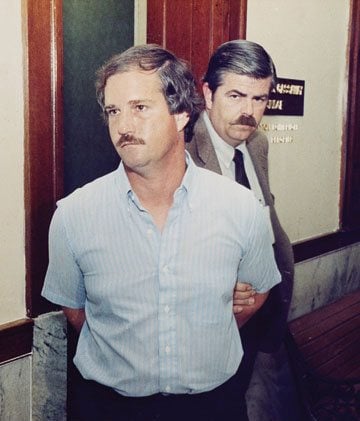

More than 15 months later, on Aug. 29, 1990, Guardiola entered the criminal justice building, subpoena in hand. Waiting in the lobby for Guardiola were a Houston police officer named Jose Selvera—a member of the police department’s “Chicano squad,” as it was then calledand a fire investigator, Hilario “Lalo” Torres. He’d spoken with both at least four times about the fire. They said they would escort him to the prosecutor’s office.

By August 1990, Selvera and Torres had become frustrated investigators. They had worked the case from the start. Torres had been specially assigned by one of the city’s most influential politicians. Houston City Council member Ben Reyes, who then represented Denver Harbor, had called the Police Department the day after the fire with a tip. He said he had heard rumors “on the street” that gang members in the neighborhood had set the Gonzales home on fire to keep the family from talking to police about recent burglaries, according to court records. This would become a key moment in the case: the moment when it became an arson investigation. Even though the tip was based on rumor and street talk, because it had come from a powerful city councilman, investigators couldn’t dismiss it. Reyes said he’d heard that an arsonist ignited the fire after pouring gasoline over the gas meter behind the house. Reyes later asked the Houston Fire Department to assign the case to Torres, who was assistant chief of the Arson Division. The fire and the four deaths had shocked the community, and the case was drawing lots of news coverage. The councilman said it was important for a Latino to solve the crime.

The problem for Torres was that rumors on the street didn’t match evidence at the scene. Six other fire investigators had pored over the charred house the night of the fire. Contrary to Reyes’ rumor, they determined the fire had started on the inside, most likely in the heavily burned back room, which the family had used as a den. Chemical testing at the scene had found no gasoline. The preliminary fire investigation report filed the night of the fire listed the cause as undetermined. All the doors and windows in the house had been locked. If fire had started inside, how could an arsonist have gotten in to ignite it?

Torres developed a theory that shoehorned the evidence to fit Reyes’ scenario. The back of the house had been badly burned, and Torres thought the extent of the burning was too great for the fire to have begun inside. So he suggested that perhaps an arsonist had poured gasoline along the outside of the house, with the fluid running under the back door and igniting the fire inside and outside simultaneously.

It was an implausible theory at best. But Torres had a bigger problem: a lack of prime suspects. Half a dozen gang members were rumored to have started the fire. A few even bragged about it around the neighborhood, probably trying to burnish an image of toughness. But Torres could find little evidence linking any of them to the crime. After a year of investigating and hundreds of hours of interviews—many of which provided conflicting information—he had no solid leads.

Torres suspected Guardiola knew more than he was saying. Guardiola wasn’t part of a gang, but he hung around and did drugs with gang members, including some who had burglarized the Gonzales home. But after repeated interviews during the previous year, Guardiola had tired of what he felt had become harassment by investigators, and he’d stopped talking to Torres and Selvera.

They wanted to bring him in for questioning. The problem was that no evidence linked Guardiola to the crime. The only reason the cops had his name was that he’d rushed to the fire scene to help. Without any probable cause, the investigators couldn’t legally detain him. To get around this, they enlisted the help of an assistant district attorney, Alice Brown, who, according to court records, issued the grand jury subpoena.

The ruse became evident when Torres, Selvera and Guardiola reached the district attorney’s office that Wednesday morning in August 1990. They met briefly with Brown, the assistant DA, but Guardiola was soon left alone with the investigators. An appeals court would later conclude that Torres and Selvera never had any intention of bringing Guardiola before the grand jury. The subpoena had been sent—just as his sister had feared—to lure him into custody.

Guardiola was interrogated for 13 hours straight. Though there was no evidence against him and he wasn’t supposed to be in custody without probable cause, the investigators handcuffed him and hauled him from Brown’s office to a police station and later to Arson Division headquarters. He was given a polygraph exam (also known as a lie detector test) that lasted two hours. Polygraphs are notoriously unreliable (error rates are upwards of 40 percent) which is why they can’t be admitted as evidence in court. One of their few uses, criminal-justice experts say, is as a police interrogation technique to manipulate defendants into confessing. Guardiola was told his answers about the fire indicated deception, but the results weren’t preserved and can’t be confirmed. (Because polygraphs are interrogation tools and not admissible evidence, police officers are allowed to lie to suspects during interrogations about their polygraph results.)

During the interrogation, Guardiola says, he was kept in a locked room. He says he was yelled at, that officers pushed him around and placed their legs between his knees to intimidate him. “They scared the hell out of me,” he says. Investigators deny that Guardiola was mistreated in any way. (It’s impossible to confirm which side is telling the truth. The interrogation wasn’t recorded; many interrogations are now videotaped, though that wasn’t common practice 20 years ago.) When Guardiola went to the bathroom, an officer escorted him there and back. (The police don’t deny this.) He says that during the interrogation, the officers kept insisting that he set the fire. Late into the night, Guardiola continued to say he had no idea how the fire started.

Around midnight, he was tiring. He hadn’t eaten in 10 hours, and he was feeling the symptoms of heroin withdrawal: severe nausea and a headache. The investigators were tired too. Torres wanted to call it a night. But Selvera insisted they keep going a little longer. He said he would question Guardiola alone, according to court records, and took in with him the photos of the victims’ charred bodies. A short time later, when Selvera emerged from the locked room, Guardiola had admitted to starting the fire.

The confession is near-perfect. Guardiola said he acted alone, so there would be no accomplices to track down. He said he started the fire exactly as Torres had theorized and as Councilman Reyes had heard, by pouring a gallon of gasoline along the back of the house, on top of the gas meter and under the door. His stated motive also matched investigators’ theory born from Reyes’ tip: Guardiola confessed to igniting the fire to prevent the Gonzales family from testifying against him about the recent burglaries.

Two days later, he recanted the confession, saying it was coerced and made up, that Torres and Selvera wrote out the confession that they wanted (the officers say the confession came entirely from him). Guardiola has insisted ever since that he’s innocent.

At Guardiola’s 1993 trial, his court-appointed attorneys tried to undermine both the forensic evidence of arson and the validity of the confession. They argued that both the supposed method and motive to which Guardiola confessed were fantastical. They portrayed Torres’ theory that gasoline ignited under a closed door as improbable, especially considering that chemical tests found no traces of gasoline at the fire scene. They also pointed out that Guardiola had no motive to set the fire. He hadn’t burglarized the house. Although he knew the people who did, he hadn’t been involved in the break-ins. He didn’t know the family, so it would have been unlikely they could implicate him.

But the jury couldn’t get past the confession. A juror would later tell the defense team she couldn’t envision an innocent man confessing to something he didn’t do. Guardiola was convicted and sentenced to 40 years in prison. With credit for time served since his arrest, he still has 20 years left on his sentence.

In the two decades that Guardiola’s been in prison, the science of fire investigation and the study of false confessions have both evolved considerably. Much of the evidence that convicted Guardiola in 1993 now looks outdated. Many of the indicators of arson that investigators once relied on have been proven wrong under scientific testing. Similarly, we now know that innocent people do confess to crimes they didn’t commit. And detailed research has revealed the kinds of interrogation tactics that lead people to falsely confess, several of which Guardiola was exposed to.

A six-month Observer investigation of the case—using new research into arson and false confessions—shows that Guardiola is probably innocent. Nationally recognized experts who examined the case at the Observer‘s request say that the fire in Denver Harbor most likely was accidental. If the fire wasn’t arson, then there was no crime. In Guardiola’s case, bad forensic work combined with a coercive interrogation may have led an innocent man to confess to a crime that never took place.

Guardiola’s case has remained unexamined for more than nine years, since he lost a final appeal in 2000. The Observer unearthed the details of Guardiola’s story while examining old cases as part of an investigation into flawed arson convictions (see “Burn Patterns” April 3 and “Victim of Circumstance?” May 29). We then asked Gerald Hurst to examine the physical evidence. Hurst, who holds a PhD in chemistry from the University of Cambridge, is one of the nation’s leading authorities on fire and explosives. In the past decade, he has helped exonerate dozens of people wrongly convicted of arson. He’s recently become well-known for his work on the case of Cameron Todd Willingham, who was executed in 2004 for supposedly starting a fire that killed his three children. Willingham was almost assuredly innocent, and his case has become a national sensation since it was profiled in The New Yorker in late August.

The Observer provided Hurst with the transcript of Guardiola’s trial, hundreds of pages of documents from the Houston Fire Department and dozens of photos taken at the scene. The first detail Hurst noticed was that investigators turned up no traces of gasoline inside or outside the Gonzales house. This seemed strange. Had an arsonist poured a gallon of gasoline around a house, you would expect to find chemical traces of it for weeks afterward, particularly in the soil along the outside of the house. Yet a technician with the Houston Fire Department thoroughly examined the home with a laser imaging system, an expensive machine sensitive enough to detect even a hint of hydrocarbons, and found nothing. Investigators then sent debris samples from both the den and the back of the house to a lab for chemical testing. Again, no gasoline was present, according to court records.

At the 1993 trial, Torres testified that deep burn patterns found in the den and along the bottom of the house’s exterior rear wall also led investigators to suspect that gasoline had started the fire. Reading these kinds of burn patterns was once a hallmark of fire investigation (and still is in some quarters). Investigators thought that gasoline fires burned hotter and faster than accidental fires and that a gasoline fire would scorch “pour patterns” into a floor where the liquid had been ignited. All of those beliefs have been debunked. Experiments over the past 15 years have shown that many of the old indicators of arson were wrong. For instance, accidental fires can burn just as hot and just as quickly as gasoline fires. (You can watch test fire videos on the Internet that show a cigarette left smoldering on a couch turn a room into an inferno within four minutes.)

The burn patterns in the Gonzales home likely weren’t caused by gasoline. Rather, Hurst says, they were the product of a phenomenon known as flashover, which occurs when heat and gas intensify to the point that a room or house literally explodes in flames. A telltale sign that a fire has reached flashover stage is when flames burst from the windows and curl toward the roof. Everyone who has looked at the case agrees that the fire in the Gonzales home reached flashover.

“After flashover and post-flashover burning, all the rules change,” Hurst says. It becomes nearly impossible to pinpoint the cause of a fire. Test fires have shown that intense burning during flashover can cause the kinds of deep burn patterns that investigators once took as evidence of gasoline.

Torres is now retired from the Houston Fire Department and living on the Gulf Coast. He told the Observer in a recent phone interview that investigators considered and “eliminated all accidental and natural causes of this fire.” Asked about the possibility that post-flashover burning caused the patterns he saw in the den, Torres said he considered that possibility but contends the burn patterns on the outside of the house must have been caused by gasoline, especially because the burn patterns stretched to the ground. Flames and heat rise, he said, so if the house’s exterior was burned at the bottom, it indicates that the fire was started at the bottom of the outside wall with gasoline “The burn patterns that I’m talking about on the outside had nothing to do with flashover,” he said.

But experiments have established that post-flashover burning will send flames spewing in all directions, including downward, which investigators once thought was impossible. If a house has an enclosed porch or a large overhang, heat will reverberate down off the overhang and char the entire wall. The back of the Gonzales house had an overhang that extended several feet. Hurst says a fire that started on the inside and went to flashover would burn out the many windows on the back of the house and the door leading to the outdoor porch. The intense heat would be trapped by the overhang and scorch the entire exterior wall, all the way to the bottom. (See photo, left.)

But experiments have established that post-flashover burning will send flames spewing in all directions, including downward, which investigators once thought was impossible. If a house has an enclosed porch or a large overhang, heat will reverberate down off the overhang and char the entire wall. The back of the Gonzales house had an overhang that extended several feet. Hurst says a fire that started on the inside and went to flashover would burn out the many windows on the back of the house and the door leading to the outdoor porch. The intense heat would be trapped by the overhang and scorch the entire exterior wall, all the way to the bottom. (See photo, left.)

Another nationally recognized fire expert, Douglas Carpenter, agrees that post-flashover fires, even ones that start inside, often scorch the outside of a house. Carpenter, who works with Combustion Science and Engineering Inc. in Maryland, says he’s seen numerous cases in which radiant heat from flashover charred the outside of a house. He also says that gasoline often won’t burn the outside of a house all that severely. He’s run tests in which he’s ignited gasoline poured on the ground around the wood exterior of a house. The fumes from the accelerant will flare up and subside quickly, and the siding of the house won’t burn for very long—in the same way that newspaper in your fireplace can burn off quickly without igniting a log.

Hurst also notes that three neighbors who saw the blaze testified that the fire started on the inside. They said they saw flames bursting through the roof above the den. They didn’t see flames on the back of the house. Maria Bernal, who lived just down the street from the Gonzales family, testified at the 1993 trial that her first thought when she saw the blaze was that the house was burning from the inside out.

Then there’s the testimony of the fire’s lone survivor, Joe Louis Gonzales. He was 13 when Guardiola went on trial. He testified that he woke in the middle of the night and smelled smoke. He walked to the bedroom door and looked down the hall toward the den. He saw his father asleep in a chair. There were no flames, he said, so he went back to sleep. A while later, he woke to the commotion of a raging fire.

Hurst says that the young Gonzales’ testimony isn’t consistent with a gasoline fire. Had someone lit gasoline in the back of the house, Joe Louis likely would have seen a tower of flames when he initially smelled smoke and looked into the den. Rather, Hurst says, the boy’s narrative is consistent with a typical accidental fire—perhaps a cigarette dropped in the couch in the den. Joe Louis might have smelled the smoke from a smoldering accidental fire. A short time later, the embers broke into a flame, which could have sent the den to flashover within minutes. Cigarettes dropped in couches are the most common cause of fatal residential fires. Both the Gonzales parents smoked in the house, according to court testimony.

It is often impossible to know for certain the cause of a fire, especially in the devastation wrought by post-flashover burning. But Hurst says it’s highly unlikely someone could have poured gasoline along the back of the house and had it flow under the door. Much of the gas probably would have tumbled off the stoop and into a 4-inch crack between the back door and the outside porch—and if so, there should have been traces of gasoline in that crevice. None were found. Even if gasoline got under the door, it’s highly questionable whether flames could burn under the door and into the den. Had the door been flush to the floor, the flames likely would have been snuffed out from lack of oxygen. A friend of the family, Daniel Wheeler, who played with the Gonzales children, testified at trial that the back door would stick to the floor, and you had to pull hard to open it.

In Hurst’s view, the physical evidence, the lack of any trace of gasoline, the testimony from eyewitnesses, all point toward an accidental fire as the most likely scenario. “I think you’ve got yourself an accidental fire here and a scapegoat,” he says.

Guardiola was a junkie. He’s upfront about that. His addiction to heroin blossomed during his three-year stint in the U.S. Army that began in 1973. Originally from Houston, he was stationed in Germany. Drugs were easy to come by and hard for an 18-year-old to resist. His drug use became so debilitating that, in 1976, the Army granted him a medical discharge. On returning to Houston, he stayed clean for a few months but soon was shooting up again. It would go on like that for years: Every now and again Guardiola would sober up, try to quit, then relapse a short time later. He earned money painting cars, mostly in his uncle’s auto body shop. Around his three sisters and his parents, he was the same gentle, quiet Fred. But they knew he wasn’t staying clean. They also knew that away from them, he often hung around a rough crowd. By the late 1980s, Guardiola’s thirst for heroin had him spending time with members of the Texas Syndicate, a violent gang that reigned over Denver Harbor. Guardiola was never in the gang, but he knew some of the members. He saw them at parties and at drug houses when he was trying to score.

He was at one of those houses on a night the Gonzales family was burglarized, a few weeks before the fire. When Guardiola arrived, the burglars had already robbed the Gonzales house. They asked him for a ride to a pawn shop. Guardiola agreed to drive them. That was the extent of his involvement in the burglaries, according to court records. After the fire—but before his confession—Guardiola served six months in jail as an accessory to the burglary.For Rosemary Garza, the fact that Guardiola never robbed the Gonzales house made his supposed motive for setting the fire unbelievable. Garza was one of Guardiola’s two court-appointed attorneys during the 1993 trial. She thought the confession too perfect. And the language didn’t fit Guardiola. For instance, the confession describes Guardiola tossing away the empty gas can near a warehouse on the “west side of Gazin [St.].” Only cops talk that way. Garza also noted that nothing in the confession could be corroborated. The day after Guardiola confessed, Torres and Selvera searched the empty lot for the discarded gas can. They never found it. Guardiola says that’s because there never was an empty gas can there. “That was part of that made-up confession,” he says.

Garza says she understands why many people are skeptical of false-confession claims, but they do happen. The advent of reliable DNA testing the past 15 years has revealed the extent of the problem. Many people have confessed to crimes that DNA testing later showed conclusively they hadn’t committed.

Richard Leo, a law professor at the University of San Francisco and one of the nation’s leading experts on false confessions, has studied hundreds of such cases. He says that of the more than 250 wrongly convicted people exonerated by DNA evidence in recent years, about 15 percent had confessed. False confessions occur for any number of reasons, he says, but a frequent common factor is police manipulation. “The psychology of it is getting someone to think that the evidence establishes their guilt, that regardless of whether they’re innocent that no one will believe it,” Leo says.

Without DNA testing, it’s impossible to show conclusively that a confession is false. But Leo says that Guardiola’s admission exhibits several traits typical of a false confession: a long interrogation, the use of a polygraph, an agreeable or easily manipulated individual and, most of all, a lack of corroborated evidence.

A 13-hour interrogation is the first warning sign. Leo’s research of hundreds of cases shows that people who falsely confess were interrogated an average of six to 12 hours. Guilty people usually confess within 30 minutes to an hour. The truth, Leo says, usually comes out fairly quickly. Of course, a 13-hour interrogation alone doesn’t mean the confession was false.

The biggest problem for Leo is the lack of corroborating evidence. Good confessions contain verifiable facts or inside knowledge of the crime. Guardiola’s confession has nothing. “There’s literally no corroborating evidence at all,” he says. “There’s just a fire, which may or may not be arson.”

Rosemary Garza would go on to become a judge in Harris County. She says she’s not one to normally believe innocence claims, but Guardiola was different. “I truly believe he’s an innocent man,” she says. Garza has refused to throw away anything from trial. She still keeps boxes and boxes of court transcripts and scene photos in her garage, just in case. She’s told Guardiola that if and when he gets out of prison, she wants to have dinner with him the first night, to celebrate.

Nine years ago, it appeared Garza and Guardiola were about to have that dinner. Guardiola’s attorneys had appealed the case, specifically challenging the legality of the confession. On March 16, 2000, a three-judge panel of Texas’ 14th Court of Appeals ruled that the interrogation of Guardiola had violated his constitutional rights under the Fourth and Fourteenth Amendments and that the confession was inadmissible.

The court ruled that Torres and Selvera’s use of the grand jury subpoena resulted in an illegal arrest. “The prosecutor’s power to subpoena must not be used as a tool for police officers to force a suspect to talk when he previously refused to do so. … We cannot allow the state to violate a citizen’s constitutional rights of due process and privacy just to satisfy its desire to ‘investigate’ a crime,” the judges wrote. The court also held that Alice Brown, the assistant DA who issued the subpoena, had violated the standards of the American Bar Association.

The court further declared, “The coercive interrogation techniques applied by Selvera was flagrantly abusive and designed to intimidate and humiliate the appellant.” Guardiola’s confession was found to be the product of coercion, given involuntarily. “In our view, this conduct was a flagrant violation of the constitutional rights of the appellant, and it leaves this court no other alternative but to reverse the conviction. … To hold otherwise would be to approve of the pretext, subterfuge, and deception practiced by the agents for the state, and blind ourselves to the rights of any accused.”

Suddenly, Guardiola had hope. But the Harris County district attorney’s office asked the appeals court to reconsider. In their request for rehearing, prosecutors pointed out that Selvera and Torres denied ever physically abusing Guardiola, and that they had read him his rights several times.

In an unusual move, the appeals court reversed itself. On May 4, 2000, just 48 days after it threw out Guardiola’s conviction, the same three appellate judges ruled that Guardiola’s confession was problematic, but admissible. In their second opinion, the appellate judges embraced Torres’ and Selvera’s version of events. The court ruled that Guardiola was never abused, wasn’t kept in a locked room and therefore wasn’t technically in “custody.” The judges still felt the use of the grand jury subpoena was unconstitutional and resulted in an illegal arrest. But it wasn’t enough, the judges said, to taint the confession. “Approximately thirteen hours had passed since [Guardiola] arrived.” That was “sufficient time” to separate the illegal arrest from the confession—a kind of buffer that made the eventual confession legally admissible. By this logic, the court reasons that Guardiola’s 13 hours of interrogation actually validates the confession.

In his recent interview with the Observer, Torres himself contradicted some of the appeals court’s findings. He told the Observer that Guardiola was indeed kept in a locked room during the interrogation. He also said that Guardiola was handcuffed while being taken to various locations throughout the day. That, Torres said, was “standard procedure” when questioning a suspect or person of interest. Torres’s recent comments seem to partially confirm Guardiola’s version of events—that he wasn’t free to leave, that he was in custody for the 13 hours before his confession.

Several years after Guardiola went to prison, his family found itself back in court, enduring another trial, this time as the victim’s family. Guardiola’s younger sister was murdered by her husband. The husband was convicted and, in perhaps the cruelest twist of all, imprisoned in the Connally Unit outside Kenedy in South Texas—the same prison as Guardiola. In that sense, prison has become even more torturous. Guardiola has seen his sister’s killer nearly every day for the past decade.

Guardiola has maintained his innocence even though admitting guilt and expressing remorse might speed his parole. He was visited recently in prison by a representative from a victims’ reconciliation group who encouraged Guardiola to meet with members of the Gonzales family to express his remorse and ask for forgiveness. It might increase his chances at parole. But Guardiola said no. He said he felt bad for the family, but couldn’t express remorse for a crime he didn’t commit.

Meanwhile, the man most responsible for putting Guardiola in prison—Torres, the arson investigator—stands by his actions. “He killed an entire family, as far as I’m concerned,” he says. “Alfredo can say whatever he wants, but the evidence was there. I’m convinced justice was done. I hope he never gets out.”

Guardiola will come up for parole next year. He’s already been turned down twice. Joe Louis Gonzales, the young boy who lost his family in the fire and is now 29, has urged the Board of Pardons and Parole not to release Guardiola. He likely will do so again.

“They’re not going to let me go. I’ve come to realize that,” Guardiola says. He blames no one but himself for his predicament. It was his fault for being weak, for being an addict, for being easily m