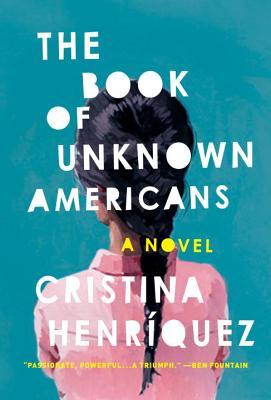

Fiction Review: Cristina Henríquez’s The Book of Unknown Americans Complicates the ‘Single Story’ of Latinos in the U.S.

Cristina Henríquez will read from The Book of Unknown Americans on June 18 at BookPeople in Austin; June 19 at Brazos Bookstore in Houston; and June 20 at the Dallas Museum of Art.

In a 2009 TED talk titled “The Danger of a Single Story,” Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie noted that “the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story.” In Texas, at least, Mexican immigration has largely defined the Latino narrative, but Cristina Henríquez’s big-hearted second novel challenges this “single story” by exploring a wide range of Latino experiences.

Henríquez is specially qualified to weigh in on the particular dilemmas of migration, cultural identity and displacement. Born and raised in Delaware and now living in Chicago, she’s resided in Florida, Virginia, Indiana and Iowa. She spent summers in Panama, where her father was born, and lived in Texas long enough to be chosen as the state’s sole essayist for the 2008 anthology State by State: A Panoramic Portrait of America. Despite her stateside bona fides, the “Americans” of her novel’s title refers to both U.S. residents and individuals from the many countries of the Américas.

The Book of Unknown Americans opens with the Rivera family’s arrival to a modest Delaware apartment building after days of travel from their hometown in central Mexico. Desperate to help their beautiful teenaged daughter, Maribel, recover from a near-fatal head injury, Arturo and Alma Rivera have come to the U.S. so that Maribel can receive special education services not available in Mexico. Why Delaware, not Texas or California? A mushroom farm in nearby Pennsylvania is the one business that will sponsor Arturo’s work visa. (Like most of the immigrants featured in the novel, the Riveras have come to the U.S. legally.)

By Cristina Henríquez

Knopf

$24.95; 294 pages

Alma Rivera narrates roughly half of the novel, quietly assessing the precariousness of her family’s new life and communicating the particular flavor of her own homesickness, taking us back to the happy life the Riveras once enjoyed, before Maribel’s accident, in their hometown of Pátzcuaro. Language barriers make phone calls to Maribel’s school an ordeal, the taste of foods from home deepens Alma’s sadness, and the hard letters of English seem like miniature walls dividing words and worlds.

Among the neighbors who help the Riveras adjust to life in Delaware are the Toros, a Panamanian-American family who live across the hall. Fifteen-year-old Mayor Toro is the novel’s secondary narrator, offering an insider’s view of the dynamics between the building’s residents and spot-on depictions of what it’s like to be the clumsy younger brother of a soccer star in a family where being “Latino and male and not a cripple” means he is expected to excel at the game.

Upon the Riveras’ arrival in Delaware, Maribel puts her clothes on backwards, forgets simple conversations held moments earlier, and struggles to wash her own hair. With time, however, her condition begins to improve. The teachers at her special school help, but readers may be inclined to give Mayor Toro more of the credit. Unlike Maribel’s parents, Mayor does not compare her to a “before” version of herself. To him, Maribel is simply Maribel: beautiful, fascinating, and—astonishingly—interested in him. The scenes between Mayor and Maribel are among the loveliest in the novel, with Henríquez perfectly coupling the awkwardness of their exchanges with their urgent quest for mutual understanding, that most basic and elusive of human sustenance. Ultimately, Mayor’s misguided efforts to cultivate their romance open the way to unwitting tragedy for both families.

If The Book of Unknown Americans has a flaw, it is that Henríquez, in her effort to overturn the “single story” of U.S. Latinos, sometimes verges on didacticism. When a character comments, “It’s like how everyone thinks I like tacos. We don’t even eat tacos in Panamá,” another Panamanian chimes in: “That’s right. We eat chicken and rice.”

“If people want to tell me to go home,” another character says, “I just turn to them and smile politely and say, ‘I’m already there.’”

There is a studied diversity to the handful of interspersed monologues from other Latino residents in the apartment building; characters including a busybody, a dancer, a photographer, a line cook with an anger-management problem and a poetry-quoting Vietnam vet hail from Mexico, Panama, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Paraguay and Puerto Rico. Nevertheless, their passages become monochromatic and rarely strike notes not already sounded more clearly in the Rivera/Toro narrative. Though a number of tertiary characters have monologues, Maribel does not. Her exclusion from the “unknown” Americans who get to speak their piece is hard to accept, mostly because it would have been a pleasure to see what Henríquez could do with Maribel’s point of view.

Henríquez is at her best when she trusts her own narrative powers, as when she portrays a wife’s grief as she browses through her deceased husband’s belongings, sucking on the bristles of his toothbrush and plucking his used toothpicks from the trash. Then she finds his hat: “I put it over my face like a mask, feeling the sweatband, soft as felt, against my cheeks. I took a deep breath. And there he was. The smell of him. I closed my eyes and felt myself sway. There he was.”

Passages like this reward a bit of patience, and The Book of Unknown Americans is a welcome contribution to a broadening literary conversation about Latino experience—a contribution that features immigrants from all across the Américas, and all walks of life. As Henríquez shows, theirs is a story composed of many stories.