Field Notes from Santa Ana

A visit to the crown jewel of the national wildlife refuge system, now under threat from Trump's wall, reveals a harsh landscape teeming with life.

A version of this story ran in the October 2017 issue.

Field Notes from Santa Ana

A visit to the crown jewel of the national wildlife refuge system, now under threat from Trump’s wall, reveals a harsh landscape teeming with life.

The Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge is a 3.3-square-mile tract of protected forest, wedged between the winding Rio Grande and the booming development of Alamo and McAllen. It’s a wild place at the intersection of desert, floodplain, scrub forest and jungle, where alluvial clay settles into sandy soils and where species at the edge of their ranges come together.

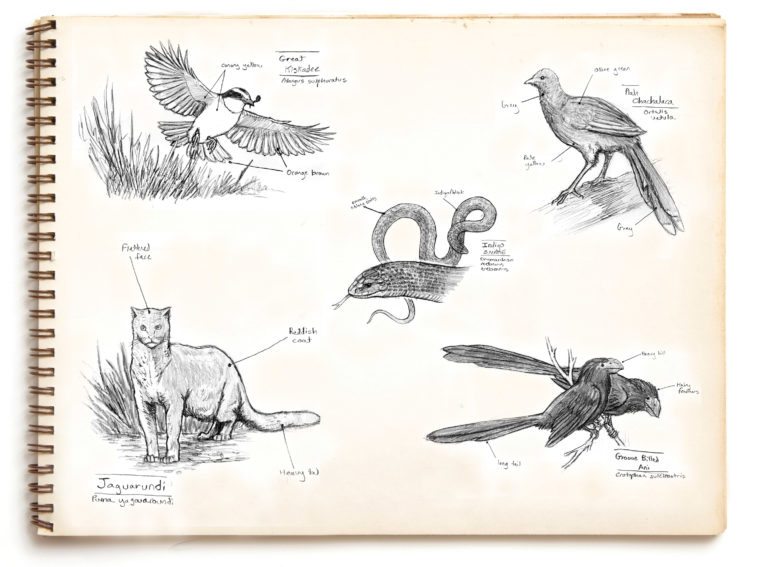

Ninety-five percent of the region’s habitat is gone; Santa Ana remains. At least 400 species of birds have been sighted inside, and 450 kinds of plants grow here, pollinated by half of North America’s butterfly species. Charismatic rarities like ocelots, jaguarundi and indigo snakes move through the brush.

The park is not well-known, even within Texas. But for birders and ecologists from all over the world, it’s a treasure. In 2016, an estimated 150,000 people visited the reserve. “So much of the Rio Grande Valley’s wilderness has been lost,” says Scott Nicol of the Sierra Club Borderlands Team. “If we lose these last little fragments like Santa Ana, that’s it. It’s gone.”

In July, the Observer broke the news that the Department of Homeland Security is moving in secret to construct a 2.8-mile segment of border wall through the refuge. Construction will cut visitors off from most of the park and fracture an already tiny block of habitat. The revelation prompted an immediate outcry from local activists and politicians. On August 13, about 680 people from across the country marched through Santa Ana to plead for its defense. I went along as well, to observe the wilderness in the shadow of the wall.

The paved trail into the refuge leads past a cheerful visitor center, across a small bridge and up and over the broad, grassy berm of the levee. It’s late morning in August, and the temperature has already hit 100 degrees. On the southern edge of the levee, the trees close in, olive and gold canopies whispering in the hot wind, sunlight baking the dusty ground. Under boughs of honey mesquite and velvet leaf, long-snouted butterflies tumble around sprigs of white flowers. I’m walking through spiny trunks with Tiffany Kersten and Jeffrey Gordon, two people with an abiding affection for the refuge. Gordon is president of the American Birding Association and has been coming here since the 1980s; Kersten worked at Santa Ana from 2012 to 2013 before leaving for the McAllen Nature Center. Both have had ample opportunity to watch the forest shift.

When Santa Ana came under federal protection in 1943, Kersten says, the Rio Grande was still in a relatively undisturbed state. The river wandered across the floodplain, leaving behind ephemeral oxbow lakes called resacas. Semiannual floods refilled the resacas and dumped drifts of moisture-trapping silt onto the sandy soil, sustaining outposts of subtropical forest among the arid thornscrub. The construction of Falcon Dam in 1954 imposed some order on the river’s wayward movement. It also ended the seasonal floods, starving the forest of silt. Without regular alluvial deposits, the riparian corridor began to dry out, leaving only the resacas preserved by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). The rare floods that arrived did more harm than good. “The refuge was underwater for four months in 2010,” Kersten says. “The vegetation was already really stressed, and the flood was just too much. We lost a lot of mature trees. What came back was this open thornscrub environment, which likes the drier soil.”

There are birds that don’t mind the transition. Groove-billed anis — black birds with heavy, blunt beaks — hop through the tangles of acacia as we pass, unperturbed by the heat. Unlike many of their fellow cuckoos, which lay eggs in the nests of other birds, anis raise their young in communal roosts. Chachalacas, chicken-sized, sociable relatives of South America’s bulky curassows, honk and crash in the thickets. Gordon points out signs of other inhabitants: the hanging woven nest of an altamira oriole, the elm trunk with a neatly drilled row of holes left by a yellow-bellied sapsucker.

The trail winds; the forest changes. Approaching the resacas, the honey mesquite falls away, replaced by tall stands of Rio Grande elm and ash, drunken trunks and low-hanging branches swathed in drifts of Spanish moss. Rose-bellied lizards peer out from the narrow roots of tepehuaje trees, bobbing small warnings of our approach. Standing on the banks of the resaca, we look out across an expanse of tilled, cracked soil, bordered in tufts of green grass. In the winter, Kersten says, the park pumps water up from the river and refills the marsh, simulating the vanished floods and providing feeding grounds for passing waterfowl. The water has to be purchased, and there isn’t money to keep the marsh constantly underwater. This is the driest she and Gordon have ever seen it. It’s clearly been managed, however: Tilling the soil stops trees and marsh grasses from encroaching, keeping a diverse cross-section of microhabitats for birds.

Nor is the resaca entirely dry. Around a bend in the path, we come to a handsome bird blind set up over a foot-deep trickle of water and thick bullrushes, the air buzzing with dragonflies. A pair of Harris’ hawks, one of the only raptors that hunts in packs, doze in the shade. At the other end of the dry marsh, two black-and-yellow kiskadees work a puddle for tadpoles, paying little attention to the nearby predators. The kiskadees have been flourishing of late, Kersten says; common in Mexico, they’re opportunistic and pugnacious, happy to gobble up anything from insects and seeds to dog food.

Santa Ana sits at the edge of two distinct faunal regions, those of subtropical Central and South America and the cooler United States. There are no chickadees in the preserve, few woodpeckers and only a single corvid, the Mexican green jay. Many of the bird species here have a tropical tinge: brightly colored flycatchers, orioles and kingbirds. Then there are the sojourners — songbirds, raptors, and waterfowl passing through on their way to Central America.

There have always been immigrants coming across the borderland: In the Pleistocene, cats and camels went south while ground sloths and terror birds came north. Nine-banded armadillos passed through in the 19th century. Now the migrants are mostly feathered. Mexican grackles have exploded up into the United States over the past 50 years, while kiskadees and clay-colored thrushes seem to be following suit. “It’s definitely undeniable that these southern species are coming north, and that northern species are retreating,” Gordon says. As the climate shifts and ecosystems change, more and more birds are likely to leave the Rio Grande behind.

There’s rarely much sign of large animals on the reserve, but they’re here. Visiting the park with photographer Eugenio del Bosque the morning after the protest, we come across a Texas indigo snake crossing a caliche trail in the southern part of the refuge, near the banks of the Rio Grande. Indigos are imposing, intelligent snakes, growing to lengths of 8 feet and feeding on rats and rattlesnakes with equal aplomb. Their inclination toward large territories leaves them threatened by development and road-building; their numbers are declining.

The same can be said for the refuge’s more enigmatic and sought-after inhabitants. Here at the limit of their northern range, hemmed in by the loss of habitat, ocelots are increasingly rare: Only 50 remain in the United States, all in South Texas. In 2016, at least one pair produced kittens in the nearby Laguna Atascosa reserve, a large tract of land on the coast. Santa Ana is too small for them to breed in, but they do visit on occasion. According to local bird guide Mary Gustafson, one female ocelot moved in for a time; USFWS tracked her moving over the majority of the refuge before she disappeared back across the river. The small, flat-faced jaguarundi might still live in the reserve too, though it’s hard to say. Even by feline standards, they’re remarkably secretive.

Santa Ana’s small size leaves many of its inhabitants in a vulnerable spot when it comes to the outside world. Animals need space, and in an urbanizing world their movements are more circumscribed than ever. “We’ve been building borders to migration all across the globe,” says Scott Egan, a biologist at Rice University. In the Lower Rio Grande Valley, those borders are constructed as much of empty farmland and box stores as they are of fencing. In 1979, a coalition of conservation partners led by the Lower Rio Grande Valley National Wildlife Refuge began slowly assembling a corridor of wild land along the river, where animals would be sheltered from encroaching development.

While the corridor is still incomplete, now and then conservation agencies are able to purchase new plots, tearing out invasive plants and reforesting with native trees. In one year, Gustafson says, bare dirt can transition to thickets of tepehuaje trees, which grow 7 feet in a year and provide shade for the slower-sprouting saplings of canopy trees. “The closer it is from a natural forest patch, the more the birds will bring fruits and seeds over and plant what they want in the revegetation area,” she says. “They’ll bring in their favorite foods … but it takes a while for them to be willing to breed there.”

These attempts at conservation are often helped along by public interest and support from locals and ecotourists. As long as visitors respect the habitat, Gordon said on our resaca hike, it’s good to have them there. When people can’t enter, reserves tend to suffer neglect, and management priority wanes. Since 9/11, increased security along the border has led to the construction of fencing and the closing of certain public lands on the river. There are ecological ramifications to this, of course: Fences block the connectivity of habitats, splintering territories and making rare animals more vulnerable.

Walls affect visitors, too. Since the fences went up, Gustafson has heard concerns about border safety from some of her clients. Private properties like the Sabal Palm Sanctuary, which has a segment of border fence built through the property, rely heavily on visitors for attention and finances. If that supply of people dries up, or access to the forest is curtailed, looking after these forests gets harder. In time, Gustafson says, some of these preserves are hardly taken care of at all.

Eight miles west of Santa Ana, in a green and pleasant park just north of the levee, sits the Old Hidalgo Pumphouse Museum, a monument to the agricultural infrastructure that helped harness the Rio Grande. Just beyond the levee are several miles of border wall, 34 feet of concrete and rusting steel towering over the riparian forest. The gate that was supposed to be left open for birders and hikers is seldom open, if ever. Hikers or park officials who want to access the forest have to walk miles out of their way to get around the barrier, often in blazing heat. Most don’t bother. Beyond the wall, the deserted trails are carpeted in seedpods and encroaching grass; mesquite branches press down in tangled curtains, and red ants trundle along the pavement.

There is an ominous quality to that forest, a gnawing loneliness that settles in slowly among the whispering grass. The border wall summons the feeling of transgressing against a natural divide. Which, of course, is the point. The wall is as much a state of mind as it is a physical construction, built less as a show of strength than a show of fear: fear of the inconstant borderland, the blended space where things move according to their own rhythms. The patchwork woodlands and wandering waters, the creatures at the edge of their range and those expanding beyond it: The wall has no place for them.

For now, Santa Ana remains open. Standing on the levee in the dawn hush, there’s no sound but the whine of the cicadas and the whispering of cool winds. Drowsy chachalacas perch in the canopies, awaiting the first rays of sunlight; marine toads gulp in the leaf litter. High above, the vultures float on the air currents, looping over the Rio Grande, north to south, south to north, as if the border does not exist.