This article is a follow-up to Follow the Money, originally published in May 2021.

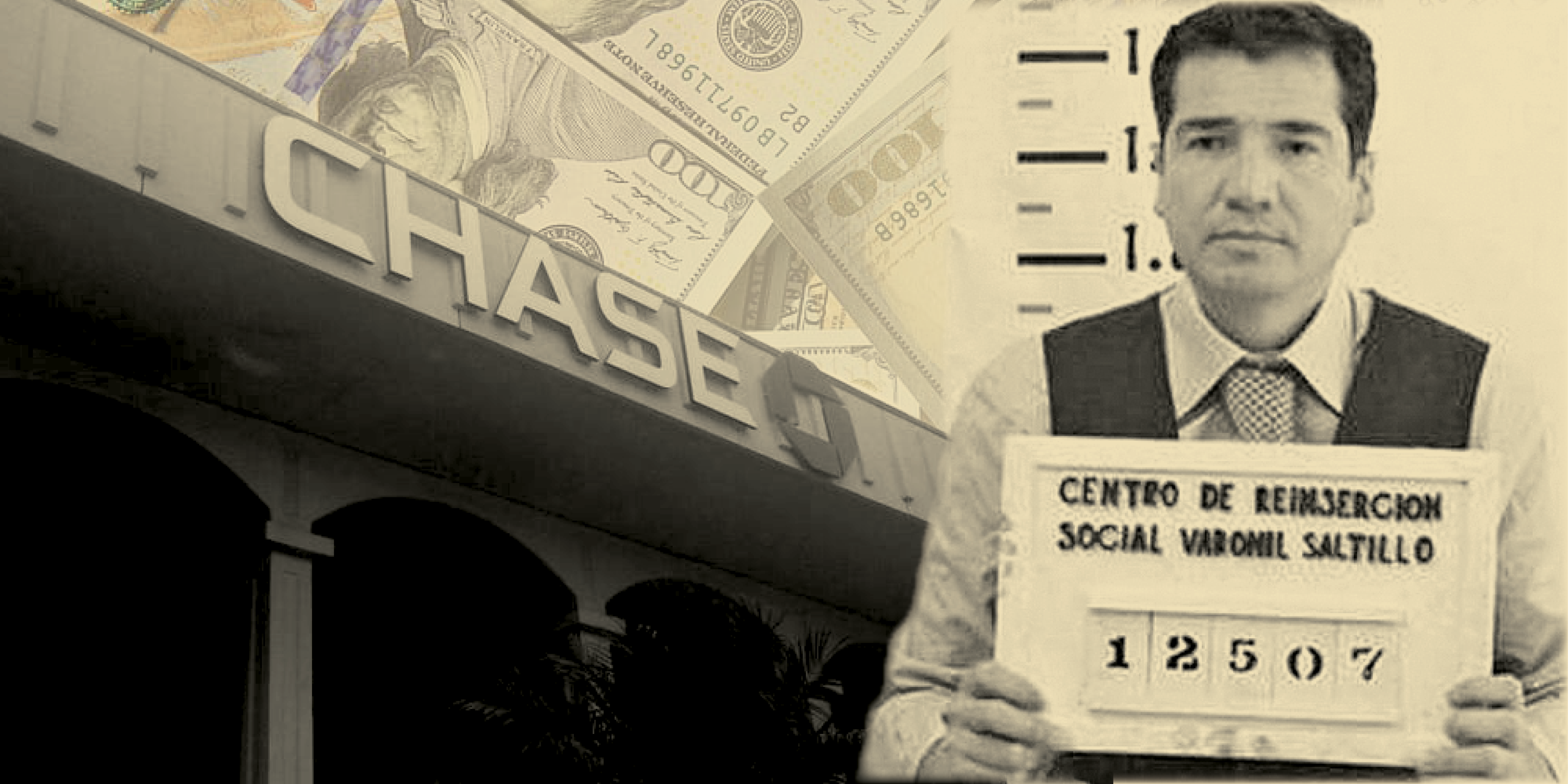

Every time Chase Bank employees in Texas asked Héctor Javier Villarreal Hernández how he earned his money, he gave a different response.

It came from his family’s restaurant businesses in Mexico. A Mercedes dealership he owned. Airplane sales he brokered to the state of Coahuila, which borders Texas from Laredo to Big Bend.

Employees at Chase investigated Villarreal Hernández again and again between 2008 and 2010, according to court records filed in San Antonio and Corpus Christi. The amount of money grew from several thousand dollars in cash deposits to tens of millions of dollars in wire transfers from Mexico. Court documents detail what money laundering experts say were a series of red flags: Villarreal Hernández gave contradictory, ever-changing explanations for his wealth. He tried to hide from Chase that he was in fact one of the most powerful public officials in Coahuila. He was arrested by Mexican officials in 2011 on charges he defrauded Coahuila’s government. But despite all that, the bank kept doing business with him. Until February 2012, that is, when an investigator with the Texas Attorney General’s Office walked into a Chase branch on San Antonio’s north side with a search warrant seeking information on Villarreal Hernández’s accounts. The investigator found $6.5 million that, according to allegations in court records, Chase knew belonged to the former Coahuila state treasurer sitting in eight different accounts.

There’s no indication in federal court records and regulatory filings that the bank, or anyone associated with it, ever faced repercussions for the tens of millions of dollars that Villarreal Hernandez, and others had stolen from Mexican taxpayers that passed through its accounts over four years, according to Observer interviews and reviews of federal court records. The money that passed through Chase accounts was used to buy a condominium on South Padre Island, a house in San Antonio, a strip mall, two apartment complexes, a car wash, a gas station in Brownsville, and a pharmacy across the street from the Chase branch in San Antonio’s exclusive Stone Oak neighborhood where officials seized Villarreal Hernández’s $6.5 million. A corporate spokesperson for Chase, Trish Wexler, declined to comment for this story.

As the Texas Observer reported in May, the U.S. has accused kleptocrats from four Mexican states of laundering money through Chase and other U.S. banks in the last decade. Corrupt officials took kickbacks for inflated contracts in Mexico, then used the bribe money to purchase real estate across Texas. After U.S. officials seized tens of millions of dollars in real estate and bank accounts, they abandoned their investigations. The allegations are detailed in hundreds of documents made public during a pair of money laundering investigations conducted by federal, state, and local authorities in Texas.

But a federal operation called Politico Junction, and a similar operation dubbed Green Tide, also offer a detailed account of bank transactions and glimpses of the secretive internal investigations financial institutions conduct of their customers. The court records that trickled out over the last decade give additional insight into how willing banks were to do business with foreign officials like Villarreal Hernández, even as their activity tripped wires internally. The Texas Observer and the Anti-Corruption Data Collective, a group of researchers and journalists who advocate for policy and legislation to curb transnational corruption, reviewed actions taken by federal regulators against banks mentioned in the court documents and found that U.S. banks rarely faced serious repercussions for their involvement in laundering money. Villarreal Hernández was indicted in 2013 by a grand jury in Corpus Christi as a result of Operation Politico Junction. In 2014, he surrendered to federal agents at the border in El Paso and was transported to San Antonio, where federal prosecutors unsealed an additional indictment against him. He pleaded guilty to money laundering offenses and agreed to turn over millions prosecutors had seized from his bank accounts.

More than a dozen banks are mentioned in the court records, but the documents offer varying degrees of detail and some information remains under seal. Documents released in asset forfeiture lawsuits and criminal prosecutions in San Antonio and Corpus Christi paint a particularly detailed picture of Villarreal Hernandez’s relationship with Chase. Chase is one of three banks that continued doing business with people who later admitted to laundering money after investigating those clients’ suspicious activity, court records show. At least five banks accepted new customers who’d recently been forced to leave other financial institutions because of suspicious activity, according to the documents.

Local and federal prosecutors considered the banks victims of fraud. They said Villarreal Hernández and other state and municipal level officials from across Mexico repeatedly lied to bank employees to hide the fact that they were public servants. They had good reason to lie. According to prosecutors, officials from four Mexican states were operating a complex kickback and money laundering scheme, taking bribes from government contractors and washing it in the U.S. Hundreds of millions were bilked from Mexican taxpayers—Coahuila’s debt alone now sits at more than t $1 billion—and at least $100 million was laundered through Texas banks and real estate transactions.

Under U.S. law, those officials were politically exposed persons, or PEPs, a term that generally includes current and former foreign officials and their families. U.S banks are expected to take steps to learn if their foreign clients are PEPs and have policies in place to ensure they’re not laundering money through the country’s financial system.

In court earlier this year, Villarreal Hernández testified that U.S. bankers knew their clients were Mexican public servants. “They never asked us if we worked for the government because they already knew,” he told a judge in May.

Officials with the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of Texas prosecuted the Mexican kleptocrats who laundered money through Chase and several South Texas banks, but wouldn’t answer questions for this story.

U.S. law requires banks to take steps to curb money laundering, including issuing reports about suspicious transactions to the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, a branch of the Treasury Department known as FinCEN. Regulations require banks to figure out how their clients earn their money. But the court documents in those recent Texas kleptocracy cases raise questions about whether U.S. banks are serious about stopping money laundering, or if they’re just checking boxes and moving on, money laundering experts said.

“The banks realize it’s the cost of doing business,” said Alvan Romero, a former special agent with the Internal Revenue Service’s criminal investigative division. “They make a lot of money doing business with corrupt individuals. But if they get caught, they do a risk assessment. They have to pay lawyers and they have to pay fines, but I think they’ve built that into their risk assessment model.”

In some cases, banks closed out the accounts of suspicious customers, showing they had the capacity to investigate and act if they chose to do so. In 2008, after he didn’t respond to their inquiries, Chase ended its relationship with Jorge Juan Torres López, another high-ranking Coahuila official. Torres López’s interactions with the bank had been suspicious from the beginning, prosecutors later alleged. After being introduced to bankers by Villarreal Hernández, Torres López wired millions of dollars from Mexico to Chase bank accounts in the U.S, then to a Bermuda investment account a Chase financial adviser had sold him. According to court records, Torres López asked bankers to delete records of his wire transfers and later demanded that his statements be sent to a banker’s house in the U.S., not to his own address in Mexico. The banker is not named in the court records.

Paul Pelletier, a law professor and former financial crimes prosecutor for the U.S. Department of Justice, reviewed excerpts of the court documents and called the request by a foreign official to send the statements to the personal address of a banker as “the biggest red flag that I saw in there.”

“How could that ever, ever be OK?” Pelletier asked. At that point the banker should have immediately rejected the client, he said. “You’re talking about a PEP. Close the book, blow out the candle, ring the bell. The experiment is over. That account definitely isn’t opened.” He said that the years of suspicious activity detailed in the Green Tide and Political Junction court records and the happenstance nature of Villarreal Hernández’s investigation—a Texas-based financial crimes task force started looking into him after he was stopped in East Texas with $67,000 in cash—show shortcomings in bank procedures and in how the U.S. prosecutes financial crimes.

Some of the suspicious wire transfers that triggered the bank’s investigation of Torres López involved Villarreal Hernández. But the bank accepted Villarreal Hernández’s explanations and kept doing business with him, records show.“It’s very clear that none of his answers are satisfactory, and there’s nothing he’s saying in there that will really generate that kind of quick money,” Pelletier said. “It’s patently bullshit.”

Only two banks mentioned in the court documents faced punishment from regulators in the Operation Politico Junction cases, both for failing to report suspicious financial activities to FINCEN. Only Lone Star National Bank in Pharr faced serious sanctions: $2 million in civil penalties for repeatedly failing to implement sufficient anti-money laundering protocols. The Observer’s and the Anti-Corruption Data Collective’s review of enforcement actions by federal regulators over the last 10 years found only one other bank that was punished for its role in the money laundering uncovered by Green Tide and Politico Junction.

Villarreal Hernández, who’s free on bond awaiting sentencing on money laundering conspiracy charges, wouldn’t comment for this story. His attorney, Michael Wynne, said he couldn’t discuss the specifics of Operation Politico Junction, but cautioned against drawing conclusions about individual bankers from the court records. Wynne, a former federal prosecutor who has been involved as a private attorney in civil litigation against several major financial institutions, said bank employees are often simply following internal policies and aren’t likely to take steps that will drive off customers.

The U.S. has among the toughest banking laws in the world, but the regulations themselves are intentionally vague, said William Watkins, a longtime Texas banker and former federal regulator. The idea is to let banks develop anti-money laundering policies based on their size and customer base, which are then subject to review by regulators. Banking laws require financial institutions to issue what are called “suspicious activity reports” when they’re concerned about customers’ transactions. Known as SARs, these reports are sent to FinCEN, which analyzes them for trends; regional SAR units plumb them for criminal leads. Banks can close out accounts and require customers to move elsewhere, but this is often motivated by business considerations, not law, said Watkins. Setting an industry-wide standard for closing accounts would be “too onerous,” Watkins said.

It’s not clear from the court records whether Chase issued SARs after it investigated Villarreal Hernández and Torres López. The reports are so secretive, federal agents can’t reference them in their affidavits. If Chase did issue SARs for Villarreal Hernández’s suspicious transactions, that may be why the bank never faced punishment.

Federal regulators can shut down banks that don’t comply with money laundering laws and prosecutors can indict bank employees, but both are rare. When banks are punished, the fines are rarely significant enough to disincentivize doing business with high-value customers involved in suspicious activity, anti-money laundering experts said. As long as banks flag suspicious activity they’re generally inoculated against punishment. But the secrecy and sheer volume of SARs make them difficult for law enforcement to address: FinCEN receives more than 2 million SARs a year.

Pelletier has called for a “white-collar-crime czar” to coordinate financial investigations and train federal prosecutors. The unsophisticated money laundering scheme Villarreal Hernández employed could have easily been identified by a comprehensive analysis of SARs, Pelletier said. “This is raw stuff that if someone has the right data systems in place… it would be caught in a New York minute,” he said. “We need to start figuring out how to address financial crime in the 21st Century.”

After Chase closed out his account, Torres López turned to one of the people paying him bribes, a Mission resident and paving magnate named Luis Carlos Castillo Cervantes, to help him launder money. To get paving contracts in Coahuila, Castillo Cervantes testified in May, he paid kickbacks to Torres López and Villarreal Hernández, who then laundered a portion of that money in the U.S.

Castillo Cervantes testified that in the late 90s or early 2000s he purchased about 7 percent of McAllen’s Inter National Bank for $3 million to $4 million. Prosecutors alleged Castillo Cervantes, who wouldn’t comment for this story, used his ownership of Inter National to help officials launder the bribes he paid them. At one point, according to prosecutors, he even arranged for a professional money launderer named Guillermo Flores Cordero and a PEP named Oscar Gómez Guerra to meet with bank officials. (Gómez Guerra was indicted in 2014 on charges of money laundering conspiracy and operating an unlicensed money transmitting business. He’s a fugitive.) The accounts Flores Cordero opened were used to launder about $30 million through Inter National, according to court records. At least one other bank got wise to his scheme—in 2011 Wells Fargo closed out his accounts. But when he pleaded guilty to money laundering conspiracy in 2014, among the assets Flores Cordero agreed to forfeit was a $3.87 million certificate of deposit at Inter National. Flores Cordero also agreed to turn over nearly $350,000 in accounts he and his wife held at HSBC and almost $1 million at UBS, both banks that prosecutors say investigated his suspicious activity in 2011 and 2013, respectively.

On at least four occasions between 2008 and 2012, the Green Tide and Political Junction court records show, when one bank decided to end their relationship with a suspected money launderer, another bank was ready to do business with them — sometimes within 24 hours. Edward Rodriguez, a former IRS agent, said there’s no formal way for banks to share information about suspicious customers. When he was working at the Treasury Department’s headquarters in 2007 and 2008, Rodriguez said, some banks proposed a centralized database of customers who were forced to leave because of suspicious activity.

“It was a good idea but it never really happened,” Rodriguez said. “The problem is that you’re basically passing the buck.”

No employee of Inter National or Banorte, the Mexican banking giant that was majority owner at the time, was ever indicted as part of that money laundering case. But U.S. financial regulators did take action against Banorte. Brian Anthony Simmons, at the time Banorte’s chief compliance officer, was suspended for 30 days. U.S. financial regulators found that Banorte had been sufficiently neglectful to warrant a $475,000 fine, about 1.7 percent of the money Flores Cordero and others laundered in the bank.

Castillo Cervantes pleaded guilty to one count of money laundering conspiracy in 2017 and was sentenced to probation earlier this year. As part of his plea he agreed to turn over $5 million, as well as cars and jewelry seized from his house. He testified in May that when he sold his Inter National shares—a Texas family purchased it in 2017—he made between $25 and $28 million.

Rodriguez, the former IRS agent who worked on money laundering and fraud cases, said the fine levied against Banorte is not sufficient to discourage banks from doing business with figures like Castillo Cervantes and Flores Cordero. “These banks have so much money, they can survive whatever penalty you’re going to charge,” Rodriguez said. “They pay the fine and they move on.”

This story is part of Reporting the Border, a project of the International Center for Journalists in partnership with the Border Center for Journalists and Bloggers. Freelance Investigative Reporters and Editors (FIRE) provided reporting assistance for this story.