Preview: The Ghost of Frank J. Robinson

Presented in partnership with Texas Public Radio, an investigation of the death of an iconic civil rights leader, ruled a suicide by local police. Documents proving he was murdered mysteriously vanished.

A version of this story ran in the November / December 2022 issue.

This story was produced in partnership with Texas Public Radio.

Look for “Frank J. Robinson’s Ghost Haunts East Texas” in the November/December issue of Texas Observer magazine and subscribe to “The Ghost of Frank J. Robinson” podcast on Texas Public Radio. The first two episodes are available today, wherever you find podcasts.

Below is a short preview of our upcoming magazine article, available next month:

Dorothy Redus Robinson didn’t believe in ghosts, but she always said she knew her husband was murdered because his ghost told her so.

In an interview recorded when she was 85, Robinson said she was sitting on the edge of her bed days after Frank J. Robinson’s funeral when she saw him again.

“It looked like he came to the hall and stood at the bedroom door, and he said, ‘Dear, it’s a lie,’ and I said, just as plain as I’m talking to you, ‘You don’t need to tell me, I know you didn’t kill yourself.’”

Dorothy said she was wide awake by the time the conversation ended.

“Then he just faded, just faded back,” Dorothy added. “He didn’t come forward. I didn’t see any movement of arms or legs.”

In life, Frank J. Robinson had always been one to come forward. He was a fearless civil rights leader and voting rights advocate who broke down barriers for Blacks in East Texas. From his home base in Palestine, Robinson, then in his 70s, was actively leading an effort called the East Texas Project in the 1970s.

In 1973, he filed Robinson v. Anderson County Commissioners Court in federal court and successfully harnessed the Voting Rights Act to end the gerrymandering of Black voters at the county level in East Texas, a practice used to dilute their power at the polls.

By 1976, he planned to expand on his legal victories and export his strategies of empowering Black voters to surrounding counties. He was planning further action to register and organize voters to help elect Black candidates, too.

“He said, ‘Dear, it’s a lie,’ and I said, just as plain as I’m talking to you, ‘You don’t need to tell me, I know you didn’t kill yourself.’”

Then, on October 14, 1976, 74-year-old Robinson was found dead in his garage. That morning, his body was discovered by a neighbor, John Cook, who came by to ask for some of the watermelons that Robinson was growing in a lush backyard garden.

Cook knocked on the front door and when no one answered, he went to the side door next to the garage. There, he spied a pair of legs laid out in a pool of blood on the garage floor.

He ran next door to Story Elementary School for help.

Palestine police were called and found Robinson stretched out on the concrete floor. The top of his head was blown off and there was a double-barreled 12-gauge shotgun lying across the body. (The records conflict on where it was found).

Palestine Police Chief Kenneth Berry immediately determined this was a homicide. “From the evidence gathered at the scene, an autopsy report, and the information taken from his widow, we have concluded it was not a suicide,” Berry told a reporter for the Palestine Herald Press.

Dorothy was out of town the day her husband died. As president of the governor’s Advisory Council for Technical-Vocational Education, she had been in San Antonio and then in Minneapolis for conferences.

The last time she’d spoken with Frank was by telephone October 10, only three days before his death. “I called him Sunday afternoon after I got to Minneapolis and he said, ‘We’ve had a little cold snap and I can’t find my long underwear.’”

Dorothy told him where to find it. “But you won’t freeze to death till I get there,” she teased. She told him that her plane would arrive at 10 o’clock that Thursday. “And he repeated the time. And that was the last conversation we had. Probably the last thing I heard him say except ‘goodbye.’”

When her plane landed in Tyler, Dorothy knew something was wrong when she didn’t see Frank. “I could always see him standing out because the plane was so small,” she said.

“When I got out, my sister, her husband, and a friend and his daughter were standing there, and I said, ‘Where is Frank?’”

Dorothy’s sister threw her arms out but didn’t say anything. The friend’s daughter said, “dead.”

“Car wreck?” Dorothy asked.

“No, somebody killed him,” she said.

“Well, get my luggage,” Dorothy said. “I’m ready.”

By the time Dorothy got home, police had already cleaned up, removing almost all signs of the violent attack. Dorothy would later argue that in their rush they destroyed valuable evidence. But some gruesome artifacts of the horror weren’t so easy to wipe away: Some of her husband’s brain matter remained on the wall.

Police questioned Dorothy. They wanted to know “if I had any inkling that he had been threatened,” she said.

Frank often received anonymous, menacing phone calls but ignored them.

“He was just that dedicated to bringing change to East Texas,” Dorothy said. “So often he would say, ‘Change is always painful,’ and he’d say, ‘But what is a little bloodshed? Because it takes that to get change—my blood or yours or anybody’s. Blood changed a lot of things.’”

Berry had been Palestine’s police chief for a year when he began investigating Robinson’s death. He had previously worked as a lieutenant in the Waco Police Department, where he oversaw the vice unit. Berry would go on to serve as Palestine’s police chief for four years before becoming Palestine’s city manager. This was by far his most controversial and sensitive case.

Some of the people whom Frank had angered through his work were Berry’s bosses: members of the Palestine City Council.

Robinson’s death happened only a week after he had won a legal fight to force that governing body to create single-member districts. The lines were redrawn in a way that enabled the city’s first two elected Black council members to take office.

News of Frank J. Robinson’s murder made it into newspapers across Texas and around the nation. The Call, an African American weekly newspaper in Kansas City, Missouri, carried the story with the headline “Civil Rights Leader in Texas Shot and Killed From Ambush.”

The Associated Press quoted Police Chief Berry: “We have no suspects. We do have leads we’re working on.” Berry made a plea to the public for any information.

A group of prominent Texas Black leaders immediately questioned whether Berry would be able to solve Robinson’s murder and called for assistance from outside law enforcement agencies. Those who called on the Texas Rangers and the FBI to probe the death included John Warfield, a University of Texas professor after whom the school’s Center for African and African American Studies was later named; and state Representative Paul Ragsdale, a Democrat from Dallas.

“Change is always painful. But what is a little bloodshed? Because it takes that to get change—my blood or yours or anybody’s. Blood changed a lot of things.”

Warfield, a controversial scholar and civil rights activist, described Robinson’s death as a “Ku Klux Klan style of murder and terror.” He declared it to be part of “a conspiracy in this state to obstruct the political rights and political awakening of Black and brown people and the powerful potential constituency they represent.” By “conspiracy,” Warfield said he meant the actions of state leaders, including Governor Dolph Briscoe, in opposing the Voting Rights Act.

Warfield thought Robinson had been targeted because “he was far too aggressive. I guess he wasn’t getting old enough fast enough for the people in that area.”

Ragsdale, a civil rights icon from Dallas and one of the first Black people elected to the Texas Legislature since Reconstruction, compared Robinson to Martin Luther King Jr. and said he believed that Robinson possibly was the victim of a political assassination. He told reporters that there was talk in Palestine that the slaying may have been carried out by a hired killer ordered to make the murder look like a suicide to avoid creating another martyr for the civil rights cause.

As word spread, condolences from across the nation and from the civil rights community were sent to Dorothy, including a telegram from Coretta Scott King, an advocate for Black equality and King’s widow.

Robinson’s death brought unwelcome attention to Palestine. “The out-of-town news media has done the city of Palestine a great injustice,” Chief Berry told a reporter from UPI on October 26, 1976. “We have been depicted as being a hotbed of prejudice and oppression of minorities. Nothing could be further from the truth.”

But Dorothy Robinson, along with other Black members of the community, objected to the white police chief’s appraisal of Palestine as a racial utopia. In fact, Palestine was an unreconstructed community of the Old South that had in the past enforced Jim Crow and still openly suppressed Black voting rights, which was what Frank was fighting against when he died.

On October 27, the Palestine court received a letter written by Robert Harding, a prisoner at the Coffield Unit, which is also in Anderson County. Harding stated that he knew who was responsible for Robinson’s murder. That same day, Texas Ranger Bob Prince went to the prison to question Harding. The prisoner said he was a member of the Ku Klux Klan and was told by the imperial wizard that Robinson was an agitator and needed to be eliminated.

But Harding lacked personal knowledge about Robinson’s death and also had a history of making false claims. The Ku Klux Klan connection went uninvestigated.

At the time of his death, Frank Robinson was deep in the planning of a meeting of the East Texas Forum to be held the following month to discuss strategies to elect more Black candidates. He had already printed the tickets for the “Second Annual Leadership Convention.” Workshops and seminars on political organizing, voter registration, and running for office were planned for November 27 in Palestine.

It never happened because of Frank’s death.

Frank James Robinson was born in an area known as Mud Creek in the rural church community of Antioch in Smith County on June 5, 1902. He was the oldest of ten children. When Frank’s mother died in 1914, he had to quit his schooling in the seventh grade to work on the family farm.

That might have been the end of Frank’s education except for what happened on a day he was making a charcoal delivery in the city of Tyler. “And he said, he heard such joy and laughter up on the hill. And he wondered what everybody was so happy about. And he asked the lady who was buying his coal what’s happening up there,” Dorothy later recounted.

His customer told him about Texas College, a historically Black college established in 1894, and Frank decided to enroll.

Initially, he was told they would accept him in their high school classes if he agreed to milk the school’s cows and work the garden. The administrator’s wife took a special interest in Frank and tutored him. When the administrator moved on to lead Prairie View Normal and Industrial College (now Prairie View A&M University), Frank took the examination for college freshmen, passed, and went with him.

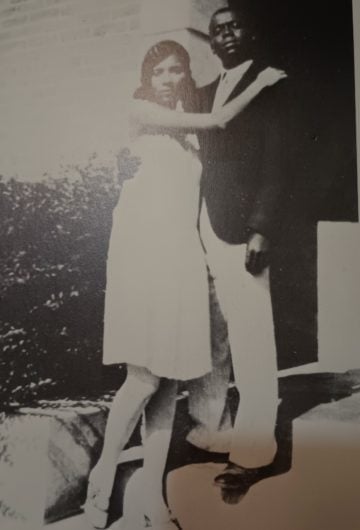

It was at Prairie View that Frank fell in love. “We met in the summer of ’27. He was working washing dishes. I was waiting tables,” Dorothy said.

“Our first date was July the fourth. At the end of the school term in early August, he said, ‘I want you to be my wife.’ I was just 18. He was 25.”

Their wedding took place in a small Ford coupe car under a tree on a dirt road outside the town of Hempstead.

“I told the preacher when he read our ceremony, ‘Don’t tell me to obey Frank, ’cause I may not obey and I’m not gonna sit up here and swear that I’m gonna do it.’ So he left it out,” Dorothy said.

Frank graduated from Prairie View in 1931 with a bachelor’s degree in agricultural science. He went to work in Palestine, the Anderson County seat, as the county agent serving Black farmers. Frank was given an office in the courthouse basement.

That’s where the Robinsons’ 46-year marriage and their many struggles and adventures began.

“I would have married him a thousand times,” Dorothy said.

Read more of “Frank J. Robinson’s Ghost Haunts East Texas” in the November / October issue of Texas Observer magazine.