Gabriel García Márquez and the (Comforting) Case for Embracing Failure

A new Austin exhibit reveals how much the acclaimed Colombian writer struggled to make a living and find success.

If you’re a writer on Twitter, there’s a fair chance this letter has popped up on your timeline in the past few days. It’s a rejection from the New Yorker—something many writers have received—but this one was sent to none other than Nobel Prize-winning Colombian author Gabriel García Márquez. On July 15, 1981, editor Roger Angell gently informed García Márquez that the magazine wouldn’t publish his story “The Trail of Your Blood on the Snow” despite it being “characterized by the customary brilliance” of his writing. The ending wasn’t convincing, apparently. Less than two years later, the Latin American author would be awarded literature’s highest honor.

As I write this, I’m contemplating a rejection letter—er, email—myself. And though I shall never aspire to García Márquez’s stature, there’s something comforting about the reminder that success rarely comes easy, even for the greats. That’s what curator Álvaro Santana-Acuña hopes visitors take away from the new bilingual exhibit “Gabriel García Márquez: The Making of a Global Writer,” at the University of Texas at Austin’s Harry Ransom Center through July 19. Among the 300 items on display, borrowed mostly from the center’s extensive García Márquez archive, is that 1981 rejection letter.

“García Márquez was a real human being, and behind this catchy idea of the genius, there was a real person who worked really hard on his writing throughout his career,” says Santana-Acuña, an assistant professor of sociology at Whitman College. “This exhibition tells a story of how difficult it is to find your place professionally.”

It also marks the culmination of a personal endeavor for Santana-Acuña. Twelve years ago, while still a first-semester graduate student at Harvard University, he was walking to the library on a wet Cambridge day. He found himself thinking that the never-ending drizzle followed by sporadic downpour was just as García Márquez described the rain in Macondo, the fictional town in One Hundred Years of Solitude. In that moment of sudden insight, Santana-Acuña was hit with a question he would seek to answer throughout the next decade: How do literary classics enter people’s daily lives and imaginations? His forthcoming book, Ascent to Glory: How One Hundred Years of Solitude Was Written and Became a Global Classic, examines how a novel that met all the conditions for failure—by an unknown author, from a relatively small publisher, and written in an unusual style for the time—ultimately became a literary phenomenon.

“When we think about bestsellers, the tendency is to think of them as destined to be successes from the beginning,” Santana-Acuña says. “But the story of One Hundred Years of Solitude is the story of a project he thought for many years would never come to surface.”

A pivotal moment for García Márquez came in 1950, when he went with his mother to his grandparents’ house in Aracataca, where he was born in 1927. Seeing the dying town of his childhood and the decaying house they were about to sell filled García Márquez with nostalgia. He felt compelled to record his memories and the stories he grew up hearing about a tragic episode in the region’s history: the 1928 massacre of striking workers at a United Fruit Company banana plantation. That was the beginning of the triumphant piece of magical realism about seven generations of the Buendía family that would take him 17 years to finish.

Now, after more than 50 million copies sold (and with a screen adaptation on the way), One Hundred Years of Solitude is at the center of the García Márquez exhibit—which also includes original manuscripts of works such as Love in the Time of Cholera, alongside first editions of Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea and other books that Márquez loved. But before Solitude’s publication in 1967, “Gabo” struggled to earn a living from his writing. As García Márquez acknowledges in his autobiography, Living to Tell the Tale, he barely received any royalties for his work until well into his 40s. When his first short story was published in a weekend literary supplement of the Colombian newspaper El Espectador, he couldn’t afford to buy a copy.

García Márquez’s years as a journalist in Bogotá and then as a foreign correspondent in Europe and Cuba fell short of providing much financial relief. While living in Mexico City in the 1960s, the father of two worked for tabloid and general interest magazines—asking out of embarrassment that his byline not be printed—and even took a one-month position as the editor of a supermarket publication. His attempts at starting a career in screenwriting also floundered. Though García Márquez was an optimist, Santana Acuña says, the letters and documents in the exhibit paint a portrait of a man who was hardly immune to self-doubt. In fact, only two years before the publication of his most celebrated work, the author remained skeptical of whether he could continue as a professional writer.

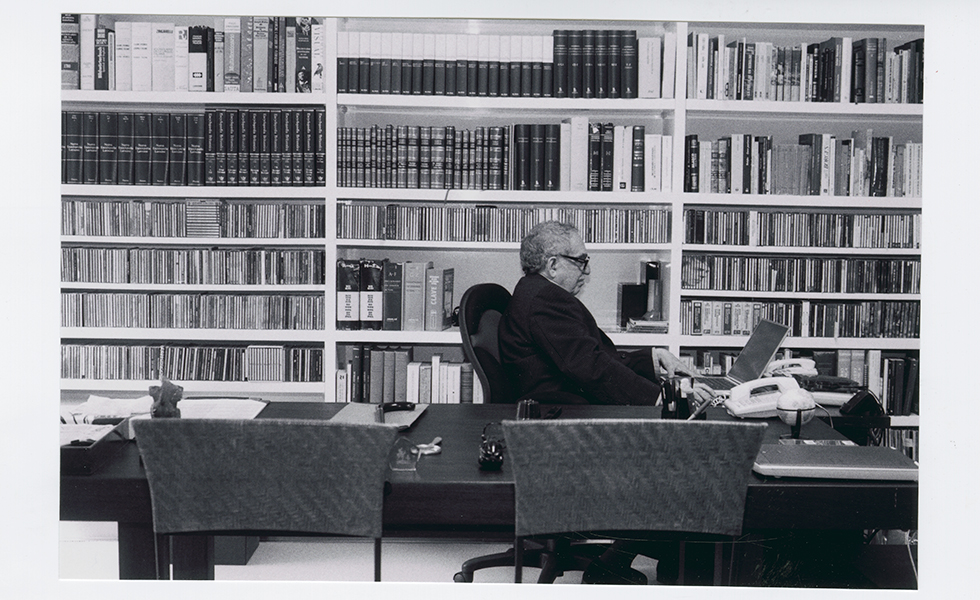

Making my way around the exhibition, I found myself coming back to a large photo of García Márquez sitting at a desk, his shoes off, his right hand scratching his head. I can’t help but wonder if he was dwelling on one of the 18 versions of Memories of My Melancholy Whores—evidence of his obsessive self-editing process on display near the photo. Or maybe he was thinking that the “terror of writing can be as intolerable as the terror of not writing,” as he would put it in his autobiography. Either way, before I left, I made sure to take note of a quote printed on the wall: “Ultimately, literature is nothing but carpentry.”

Read more from the Observer:

-

San Antonio Embraces Mandaean Refugees: If the Mandaean religion survives, it will be partly because of the refuge it found in Central Texas.

-

In Amarillo, Copper Workers’ Strike Enters Fourth Month with No End in Sight: Laborers in the Republican-dominated Texas Panhandle find themselves in a protracted fight with one of the world’s largest copper producers.

-

With Coal Plants Offline, the Air in Central and East Texas Has Cleared: After three plants shut down in late 2017, legal air pollution in Texas fell by 150,000 tons.