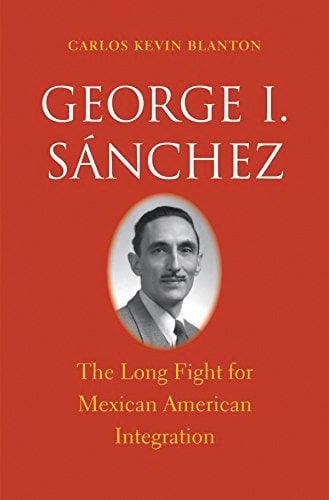

Integration Hero and Education Legend George I. Sanchez Gets a New Biography

A version of this story ran in the March 2015 issue.

Scholar-activist George I. Sanchez was an effective, relentless and cantankerous Hispanic leader in the fights against the rank racism leveled at Mexican-Americans in New Mexico and Texas from the 1930s through the 1960s. A fervent integrationist, he was a liberal and a champion of socialist education in Mexico (about which he wrote a book). He shaded into cultural nationalism in the 1970s as younger Hispanics labeling themselves Chicanos moved into leadership. Carlos Kevin Blanton, a Texas A&M professor specializing in Chicano and Texas history, in his copious new play-by-play biography calls Sanchez the most important Mexican-American intellectual between the Depression and the Great Society. At the University of Texas during and after Gov. Allan Shivers’ domination of the board of regents, Sanchez was punished with low pay for his hostility to the segregation of Hispanic students and his open support of, for example, the liberal U.S. Senator Ralph Yarborough. Eventually, though, the building housing UT’s College of Education was named for him.

Sanchez, Blanton writes, once said, “… we, Mexican Americans, were betrayed. Screwed, that is,” by the United States. Blanton’s book should be required reading in Texas as the state’s coming Hispanic majority grows into position to control Texas politics.

By Carlos Kevin Blanton

Yale University Press

400 pages; $45 Yale University Press

Born Catholic in 1906, Sanchez was raised first in a slum neighborhood a few miles west of Albuquerque, then in mining towns around New Mexico and Arizona, where he attended small public schools. In the 1930s and ’40s, Blanton writes, “hardly any” Mexican Americans graduated from the public school system—few made it past grade school. Sanchez’s parents had gotten only into third grade. His father “would monopolize my elementary school textbooks in the evening,” Sanchez said. Politically, his father was a fierce union partisan, but shied from the Wobblies. In Winslow, Arizona, when George was 14, his father was fired from a job at the local mine.

Young Sanchez was smart, driven and imaginative, and early on he saw an escape from poverty through education. He was a brilliant student and excelled in math and music (he played the cornet). To help the family he worked as a clerk and a janitor, played in an orchestra, promoted dances, prospected in two states, and boxed in the local rings. Graduating at 16, he got a job teaching in a one-room “Hispano” school on a dirt road near Albuquerque. Later he took another teaching job at a remote school in a community called “Stink-Eye” near a Navajo reservation.

At about 18 he married his high school sweetheart from Albuquerque High. Her grandfather was wealthy and powerful in the county, and George became a school principal, director of the local night school’s Spanish department, a supervisor of county schools, and originator of such policies as pre-first-grade instruction for 5-year-olds. To earn his bachelor’s degree in 1930 from the University of New Mexico, he took 19 courses through the University of California and three lesser colleges, making mostly A’s. By 1934 he had his doctorate from UC-Berkeley. His dissertation championed bilingual education.

During his meteoric but choppy career in the educational bureaucracy of New Mexico, Sanchez became a social reconstructionist in the context of the progressive education movement, favoring activist teaching against injustice and inequality. Foundation money (Ford, Rosenwald, Carnegie) flowed to Sanchez as he challenged the gospel status of IQ tests, but his successful lobbying for more state money and higher teacher wages for “Hispano” rural schools was vetoed by New Mexico Gov. Arthur Seligman. Sanchez then went to the state legislature and, in his words, “tore the hide off the Governor—I was mad. As a consequence, I was blacklisted by the Administration.”

Blanton’s book should be required reading in Texas as the state’s coming Hispanic majority grows into position to control Texas politics.

All of this steamy detail comes from Blanton’s decade of exhaustive and assiduous research, attested to by the book’s 20-page bibliography and 80 dense pages of footnotes.

Sanchez was staunchly anti-racist, but he was not immune to the appeals of classism. He took pride in being the offspring of a Spanish line of descent, and one learns from Blanton that he “constantly dwelled” on his family roots among the 17th century Spanish pioneers who settled New Mexico. Such classism, I think, may be a basis for understanding his description, to a foundation correspondent, of “The miserable, stinking, stomach-turning schools offered the Negro (and also the poor White, by the way)” in the South. “No longer a slave,” he went on, “the Negro was thrown on the dung heap—to fester, and to rot, and to stink. His community had become insane, criminally insane.”

Somewhat similarly, during a panel discussion, Sanchez once lamented the Mexican American’s situation, saying, “… he is pathetic in his helplessness—a stranger in his own home.”

I knew Sanchez. We were friends. Once, though, we came into conflict. During the Chicano uprisings of the 1970s that both influenced and to an extent alienated him, he was quoted saying “only the mexicanos can speak for the mexicanos,” later adding that “only the Negro can speak for the Negro.” As Blanton recalls, I countered that the logical political conclusion of such a position was, for example, that “mexicanos should elect only mexicanos,” and added, “Inherently, there is a danger in this work—the danger that righteousness against economic oppression that is undeniably racial in part may metamorphose into retaliatory racism.”

Sanchez replied, “I have been fighting racism since you were wearing three-cornered pants … I have numerous scars that attest to my fight against racism, in this and other countries. Have you?”

In his person, George Sanchez was a handsome man and slight, afflicted by tuberculosis and its aftereffects. During his time at UT he was permanently bent to one side and used a cane. He died in 1972 amid a compound of ailments, by then evidently including alcoholism. The Observer ran a poem by Homer Barrera titled, “Dr. George I. Sanchez, Don Quixote of the Texas Range.” In 1965, to a young Chicano who had written him impatient with the persistence of racism, our Don Quixote wrote, “Don’t expect an oldtimer like myself to hold your hand; I’ve fought, bled, and died in this game. Go out and fight your own fight. I started more than forty years ago, and am still at it. My head has been bloodied, my soul has been injured. Go out and do the same.”