‘Ghosts of Sugar Land’ Tracks a Texan’s Path to ISIS

In this contemplative, vulnerable new documentary, a group of friends try to understand why their former classmate embraced radical Islam.

One day in the summer of 2015, Bassam Tariq logged on to Facebook to see a long missive posted by a former friend, Warren Christopher Clark. “I am now currently living in the Islamic state,” Clark wrote. “I’m sure people want to know what life is like here, so I’ll tell you honestly.” Clark went on to describe his life as a member of ISIS in Syria, from the food (“You won’t find Chinese takeaway, Mexican, or sushi”) to slavery (“Slaves do exist here, but I personally haven’t seen any.”)

For Tariq, now 33, and his friends from Sugar Land—the well-heeled Houston suburb where they and Clark had all graduated from high school—the message was bizarre and disturbing, but not entirely shocking. They’d been watching Clark unravel on Facebook for years, as he’d posted increasingly radical messages about Islam. “Nobody knew what to think,” Tariq says. “It was surreal.” How had a classmate they remembered as shy, quirky, and thoughtful gone so far astray?

That question drives Ghosts of Sugar Land, a short film by Tariq that debuted on Netflix this week. In this contemplative, vulnerable documentary, Tariq’s Muslim-American friends share their memories of Clark and struggle to understand why he joined ISIS. Compelling and dark, the movie manages to cover a lot of ground in just 21 minutes.

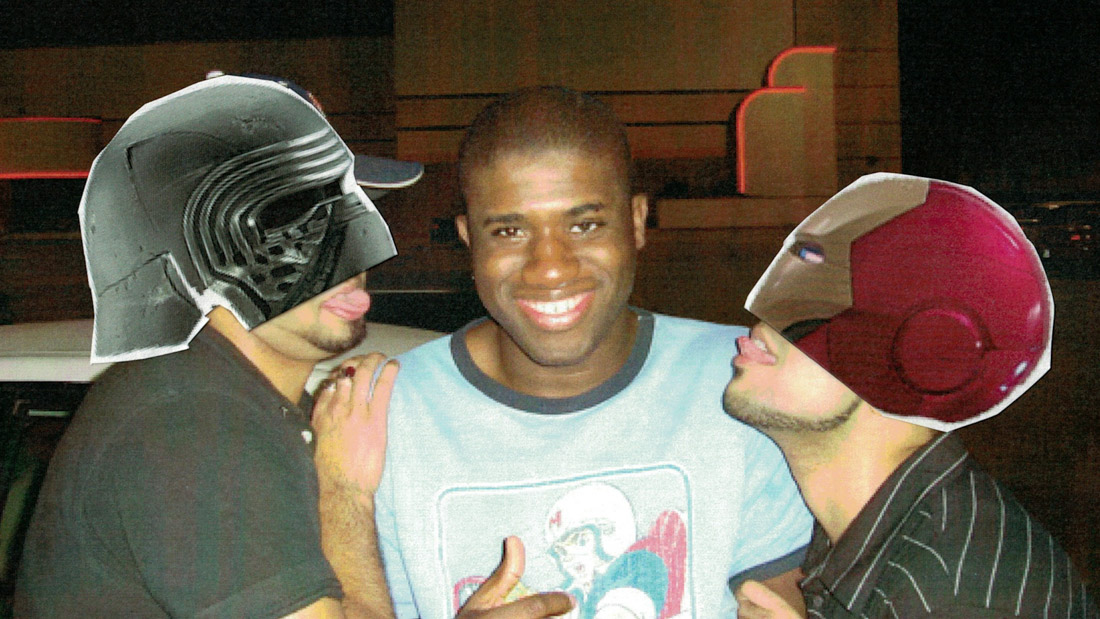

Ghosts of Sugar Land consists mostly of one-on-one and small-group interviews shot in a convenience store, in a strip-mall parking lot, and in the friends’ childhood homes. Because filming was completed shortly before Clark was captured on a Syrian battlefield and extradited to the United States, where he’s now awaiting trial, they refer to him by a pseudonym, “Mark.” And in a weird visual twist, all the interviewees wear plastic cartoon masks. “Some of these guys are working in fields like IT, and they’re afraid of being Googled,” Tariq explains, “so they wanted to be anonymous. We were playing Super Smash Bros when I suggested we wear masks.”

The result: young men discussing the difficulties of growing up as a Muslim-American from behind the visages of Mario, Iron Man, and Buzz Lightyear. Whether you find this trope jarring or effective will depend on your taste. At first the masks are distracting, but as the men delve into questions of what it means to be a “good Muslim,” it seems like a perfect metaphor. We all play roles constrained by culture, class, and race—a truth that weighs especially heavy on immigrant kids. One interviewee recalls how he was warned not to go paintballing after 9/11, since it might be perceived as aggressive; another remembers the time his mom threw out all his Muslim Student Association T-shirts, worried that they’d make him a target for bullies.

Some of the most powerful moments come from Clark’s former best friend, who wears a Kylo Ren mask. He recounts how Clark, one of the only black students in their middle school, was a social outcast. “He couldn’t wear what was traditionally considered black clothing, because people would say he’s not ‘real black,’” the friend says. “He tried the goth, emo, punk stuff from Hot Topic, kind of tried everything … and nothing really stuck.” Clark finally found his place among the Muslim-American kids, who welcomed him as a fellow outsider and inspired his conversion to Islam. But his religious fervor soon far eclipsed theirs. His new devotion to Islam left him once again on the fringes, at odds with the friends one interviewee describes as “just trying to be as American as possible.”

While Tariq graduated from the University of Texas at Austin, moved to New York City, and started a filmmaking career, and the rest of the group similarly achieved middle-class success, Clark floundered. He earned a political science degree at the University of Houston but was unable to find an office job, instead working a series of part-time gigs: stocking shelves at Kroger, driving trucks for an oil company, substitute teaching. He grew a beard and spent a lot of time ranting online, with a typical post arguing it was indecent for Muslim men to wear shorts. As his former classmates watched with horror, Clark’s transformation was so hard to believe that they suspected he might be an undercover FBI informant.

The question of what drove Clark to radicalize is ultimately unanswerable. But it’s easy to see how a rigid belief system might appeal to a naive, lonely young man searching for community. Earlier this year, Clark told NBC News that he joined ISIS “to see what the group was about,” as casually as someone else might suggest checking out a new band. (He added, “I’m from Texas. They like to execute people too.”) Clark is one of roughly 300 Americans who have run off to join ISIS; none has yet committed violence at home.

The hardest part of making the film, Tariq says, was ensuring Clark was depicted as neither a dunce nor a criminal mastermind, but rather as a nuanced person. “I wanted to show his complexity, and show how my friends are themselves complex people finding their way,” he says. “It’s a portrait of my friends through the lens of someone who disappeared.” On those grounds, Ghosts of Sugar Land is a resounding success.

Read more from the Observer:

-

Mr. Reynolds’ Opus: How Graham Reynolds became Texas’ top composer.

-

Janis Joplin’s Inimitable Voice: An authoritative new biography explores what drove the iconic Texan singer.

-

The World’s Briscoe Cain Problem: The far-right Texas lawmaker and other political trolls are holding us hostage to the idea that the world is more chaotic, unfixable, and stupid than it is.