Greg Abbott’s Own Research Shows He Could Remove a Confederate Marker at the Capitol if He Wanted To

Abbott’s recent crash course on Confederate markers shows that immediate steps to remove the Capitol plaque are available — should he find the stomach.

For the past seven months, Governor Greg Abbott has been studying what he can do about a 59-year-old plaque hanging in the Texas Capitol that denies the Civil War was fought over slavery. While many lawmakers, including the speaker of the House, want the marker taken down, Abbott has insisted its removal is complicated. His office has characterized research into the issue from the State Preservation Board as only revealing “more questions than answers.”

But that’s simply not true. The State Preservation Board research shows there’s both precedent for the governor removing the plaque and options for immediately starting that process. The research also points to a state law that empowers the Legislature, the State Preservation Board, which Abbott chairs, or the Texas Historical Commission (made up of governor-appointed members) to remove “statues, portraits, plaques, seals, symbols, building names and street names on state lands.” In other words, Abbott could begin the process of removing the offending plaque tomorrow if he chose.

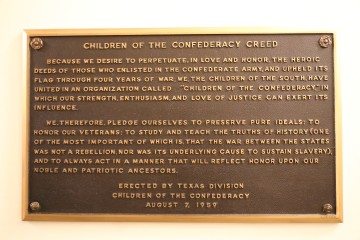

Abbott has remained conspicuously noncommittal about the plaque since last summer, when the white supremacist violence in Charlottesville triggered a national reckoning over Confederate markers and monuments. While cities across Texas have toppled Confederate statues or renamed streets and schools over the past year, Abbott has largely dodged calls to take down the so-called Children of the Confederacy Creed, which has hung in the Texas Capitol since 1959. The plaque is not subtle. It bluntly declares that the Confederacy “was not a rebellion, nor was its underlying cause to sustain slavery.” Days after the Unite the Right rally reignited the push to remove Confederate markers, including the Capitol plaque, Abbott cautioned that “tearing down monuments won’t erase our nation’s past, and it doesn’t advance our nation’s future.”

Abbott eventually agreed to sit down with state Representative Eric Johnson, a black Democrat from Dallas who’s led the charge to remove the plaque, but other than reiterating that the governor made no agreement to take the marker down, the messaging out of his office after the meeting was mostly gobbledigook. Abbott then sat silently on Johnson’s official request to take down the marker for so long that in April, Johnson and Representative Joe Moody, a fellow Democrat from El Paso, asked Attorney General Ken Paxton to draft a legal opinion on how to remove it, effectively forcing the issue.

According to emails obtained by the Observer under a public records request, research compiled by the State Preservation Board and sent to Abbott’s office shows that Texas unveiled the Children of the Confederacy creed at the Capitol around the time of the United Daughters of the Confederacy’s state convention in 1959. Originally dug into the southwest archway leading to the building’s stately rotunda, the plaque has already been moved at least once to end up in its current location near Johnson’s office.

As for completely removing a prominently displayed Confederate plaque at the Capitol complex, that wouldn’t be unprecedented, not even in recent memory.

In 2000, then-Governor George W. Bush, amid pressure from the NAACP, removed two plaques honoring the Confederacy from the Texas Supreme Court Building. Those plaques — one with a Confederate seal and a dedication to rebel soldiers, the other with a raised-relief image of a waving Confederate flag and a quote from Robert E. Lee gushing over the Confederate Army’s Texas regiment — were, like the Capitol plaque, installed during the civil rights movement. The replacement plaques, which explain the building’s history and assure visitors that Texas courts seek justice “regardless of race, creed, or color,” ultimately survived a lawsuit by the Sons of Confederate Veterans. The group sued (again, unsuccessfully) when Texas denied its request for a historical marker inside the building in 2011.

Confederate sympathizers also sued the state about a century ago in an attempt to maintain prominence at Capitol Square, according to research compiled by the State Preservation Board. The Daughters of the Republic of Texas and United Daughters of the Confederacy, the same group that would later create the Capitol’s slavery-denying plaque, began to gather relics to keep on the Capitol grounds in the late 1890s. By 1903, both groups of Daughters had secured their own spots at the Capitol. Fourteen years later, the groups sued but failed to block the state from moving their artifacts to an old General Land Office building nearby amid a supposed shortage of office space at the Capitol. Decades later, the groups decided they’d rather leave the Capitol grounds than comply with state demands that they maintain their collections by modern museum standards.

Despite that history, Abbott’s crash course on Confederate markers shows that immediate steps to remove the Capitol plaque are available to the governor should he find the stomach. Weeks after the violence in Charlottesville, Texas Historical Commission Executive Director Mark Wolfe drafted a memo for state and local officials considering their options for removal, according to emails obtained by the Observer. The memo, which was later sent to Abbott’s office, points to a portion of the Texas Government Code outlining several routes the governor could pursue to remove the plaque. The memo also suggests questions for officials to ask before deciding whether to let a marker stay in place, such as considering its original purpose and context. The memo states, “If the purpose of the original recognition was because of the group or person’s connection with shameful or reprehensible practices, or to intimidate local residents, then it is less likely that the object should be retained or remain in place.”

Outgoing House Speaker Joe Straus, a Republican who also sits on the State Preservation Board and has called for the plaque’s removal, has urged Abbott to call a board meeting to decide the marker’s fate — something only the governor can do. But as the Dallas Morning News’ Lauren McGaughy reports, Abbott’s office continues to punt — while Paxton, who has until October to issue his opinion on the matter, solicited briefs on the plaque from the governor and several other people with “a special interest or expertise in the subject matter,” Abbott hasn’t even bothered to weigh in.

Abbott’s office didn’t return our requests for comment.

Meanwhile, Abbott continues to face mounting calls for action, most recently by 12 members of the Texas Legislative Black Caucus. In a letter to the governor’s office this week, the black lawmakers call the Capitol plaque particularly offensive because of its flagrant inaccuracy. Texas’ declaration and ordinance of secession make it crystal clear that the state joined the Confederacy to uphold slavery and white supremacy.

“The plaque’s historical references are not just inaccurate, they are clear falsehoods fed to our children during a time of further subjugation of people of color,” the letter states. “We stand at a turning point in our state’s history. We must stand up for the truth.”