Will Grocery Workers Still Be ‘Heroes’ When COVID-19 Subsides?

In Texas, grocery employees labor for low wages and few benefits. Now they’re part of a nationwide struggle in which workers are fighting for their lives.

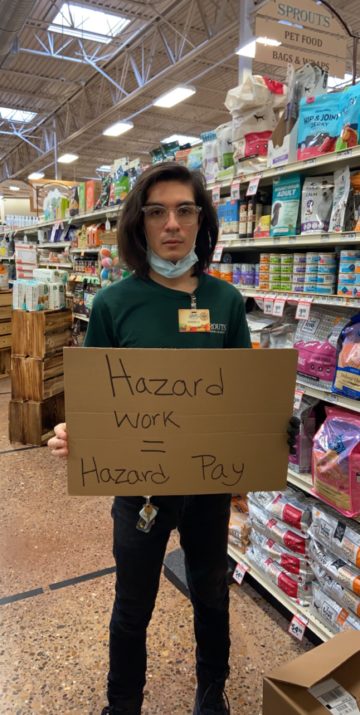

For Joshua Cano, every cough “sounded like a gunshot.” Twenty-four years old, Cano works as a vitamin clerk at a Sprouts grocery store in the Texas border city of McAllen. For all of March, Cano says, he was working without gloves, masks, sufficient hand sanitizer, or limits on how many customers could enter the store. At home, where he lives with his parents and sister, he’d anxiously remove his potentially infected clothes and bag them, wipe down his boots, and wash his hands until they blistered. Cano had to be careful: His mother, undergoing chemotherapy for breast cancer, was highly vulnerable to COVID-19. His family needed his wages, but $11 an hour would be a cheap price for a life.

Then, a little over a month ago, a friend sent Cano a message on Twitter. It was a simple graphic that read, “Fight Covid-19, Organize at Work,” with a link to a Google Form to fill out. Cano entered his information, and soon got a call from Michael Enriquez, a Kansas City-based activist who’s worked for both Bernie Sanders and Fight for $15. With Enriquez’s guidance, Cano and a co-worker got nearly all 52 employees at their store to sign onto a list of demands, and they launched an online petition that, with a social media boost from Senator Sanders, has drawn around 7,500 signatures. In early April, Cano and others presented their demands to store management, and soon after, Cano says, they received masks, gloves, hand sanitizer, and a limit on customers. (The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, it bears noting, changed its guidance on masks around the same time.)

“This was my first time really organizing,” Cano, who is a full-time student at UT-Rio Grande Valley in addition to working full-time at Sprouts, tells me over the phone. “There was a lot I learned, like strength in numbers.”

When he connected with Enriquez, Cano tapped into the Emergency Workplace Organizing Committee—an ad hoc collaboration between the 60,000-member Democratic Socialists of America and the United Electrical Workers union—which aims to help nonunion workers fight for protections during COVID-19. Per Enriquez, more than 1,000 workers have filled out the group’s intake form and hundreds have volunteered as organizers. The committee’s long-term plans are uncertain (“We’re building the plane as we fly it,” Enriquez tells me), but it’s one of many signs of heightened labor organizing in response to the coronavirus crisis.

Since early March, there have been more than 140 work stoppages in the United States, as tracked by Payday Report. From Amazon warehouse workers in Detroit to poultry plant employees in Georgia to Shipt shoppers in Dallas, workers have walked out to demand safety precautions, sick leave, and hazard pay amid a pandemic that’s now claimed more than 62,000 lives across the country. Established unions have lobbied for state and federal benefits as new labor organizations, like the Gig Workers Collective, and spontaneous worker formations have flexed newfound muscle. On May 1, International Workers’ Day, laborers across a suite of nonunion workplaces are striking.

At the heart of this upsurge are workers, now manning the frontlines of a disaster, who traditionally draw little respect in American society. Take grocery clerks, who’ve labored throughout the crisis, including the early weeks of panic-buying. In Texas, the average cashier makes just $11 an hour, often with meager to nonexistent benefits and unpredictable part-time scheduling. Suddenly, these workers find their employers are providing them with new uniforms or buying commercials to call them “heroes.” In Texas, the state labor department deemed grocery workers essential in early April, expanding their access to subsidized child care. Dallas County has granted them access to COVID-19 testing even if they lack symptoms. Some grocers, including H-E-B, Kroger, and Whole Foods, have provided temporary $2-an-hour raises, along with new paid leave. But so far, all these benefits have come with an expiration date—raising the question of who we’ll call heroes once the pandemic ebbs.

“There’s a larger issue of how this changes American society: Is this going to change how we look at hourly workers and what their ‘value’ is to society?” says Anthony Elmo, political director for United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) Local 1000, which represents Kroger workers. The only unionized grocery chain in Texas, Kroger employs some 35,000 at stores in the Dallas-Fort Worth and Houston areas. “It remains to be seen,” Elmo says, “but we need to build this narrative that these people are more valuable than what they make.”

Jackie Ryan, a Kroger cashier in the Dallas suburb of Cedar Hill, says many customers are a long way from treating grocery workers as heroes. She’s been called a “bitch,” she says, because her store had placed limits on bread and milk purchases. “There’s the physical part and the mental part of your job,” she says. “You’re literally the human doormat. Someone can curse at you and you say, ‘Thank you. Have a nice day.’”

After 10 years, Ryan makes $15 an hour, but new hires may start under $10. She’s thankful for the company’s $2 raise—which is set to expire May 16—but she’s nonplussed with the commercials lauding her: “The $2 probably won’t last because of what they spent on commercials thanking us,” she jokes. A union steward, Ryan hopes to fight for a permanent raise in contract negotiations later this year, and she hopes COVID-19 will spark a movement elsewhere. “If there’s anything that comes out of this, I hope it’s that people will unionize more and stand up for their rights and demand what they deserve.”

A Kroger spokesperson says the company “will continue to evaluate” the $2 raise and notes that, like other grocers, Kroger has installed plexiglass partitions and placed floor decals to promote social distancing. The spokesperson would not confirm specifics but says “a small number” of employees in Texas have tested positive for COVID-19. (Elmo, the UFCW staffer, says that as of last week, at least 23 had tested positive in the DFW area.) The spokesperson adds: “In every decision we’ve made—and are making—we’ve worked to balance our urgent priority to provide a safe environment for our associates and customers with open stores, comprehensive digital solutions, and an efficiently operating supply chain.”

The Texas-based H-E-B, which has received lavish praise from the press for its pandemic preparedness, granted a $2 raise in mid-March—after a petition began circulating on coworker.org—and has twice extended it. It’s now set to expire May 24. A Houston cashier, who requested anonymity, tells me: “After possibly exposing ourselves and our family members, I think we should keep the raise.” The cashier also notes that many part-time employees saw their hours cut after the raise took effect, so many have been earning less than normal during the pandemic—even as H-E-B hires hundreds of new temporary workers.

Another Houston H-E-B employee, who also asked to not be named, emphasizes that H-E-B—which enjoys a sterling reputation in Texas—has plenty in common with less popular retailers like Walmart. The company likes to hire part time, she says, allowing it to minimize benefits and slash hours as needed. “This is where American retail is at: They hire part time and we’re practically disposable,” she says, adding that she considers it a “certainty” the $2 raise will disappear. Both employees tell me that, prior to the pandemic, they usually worked more than 30 hours a week but were considered part time and did not receive paid sick leave. The petition for hazard pay at H-E-B has drawn over 4,000 signatures and a litany of comments, including: “i work there i don’t wanna die broke,” from Nina E.

H-E-B and Sprouts did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Unlike many sectors, grocers are thriving during the pandemic: Across the country, companies are hiring thousands of new employees, and Walmart alone has hired 150,000. Kroger, per the spokesperson, saw supermarket sales jump 30 percent in March, and stocks are high. That could be fertile ground for workers to demand a bigger piece of the pie.

But John Logan, a labor scholar at San Francisco State University, sees a couple possible roadblocks. For one thing, much of the hiring has been to serve a spike in demand for online grocery pickup and delivery. These new workers may come in at the bottom of the pay scale, and if the change becomes permanent, then anti-union giants will likely be best positioned to capitalize. “The very big nonunion players—the Amazons, the Walmarts—are quite likely to emerge in an even more dominant position in food retail when the pandemic ends,” Logan says.

Moreover, Logan notes, many employers have eagerly fought against worker organizing even during the pandemic. Trader Joe’s and the Amazon-owned Whole Foods, among others, have either continued anti-unionization campaigns or otherwise retaliated against employee agitators. And historically, sky-high levels of unemployment give bosses the upper hand over labor: “Unions generally don’t do well when the labor market is tanking and there’s tens of millions unemployed.” (Sure, the New Deal was born of the Great Depression, but that will be tough to replicate with Donald Trump and his zealously anti-union labor department in power.)

In a recent essay for the American Prospect, longtime labor scholar Ruth Milkman notes that many observers predicted a resurgence of labor after the 2008 financial crisis. It never happened. If it occurs this time, Milkman argues, it will depend on the radical-leaning young activists who fueled movements like Occupy, Black Lives Matter, and the Sanders campaigns.

It depends, in other words, on workers like Cano, the 24-year-old Sprouts employee. As Texas moves to reopen its economy, against the advice of data and doctors, grocery workers will remain on the front lines. Already, according to a likely undercount maintained by the UFCW, 72 employees in the grocery, meatpacking, and other retail sectors have died from the novel coronavirus. As they face possible subsequent COVID-19 outbreaks, will workers like Cano have the tenacity to see through the fraught process of reform?

Cano and his co-workers are still fighting for more gains at Sprouts, which operates stores in 22 states. They’re organizing call-ins to corporate headquarters, demanding hazard pay and a workers’ safety committee. When Cano started organizing, he was fearful of being fired during a pandemic. But as he learned about his rights as a worker, he grew emboldened. “Once I was educated, my fears dissipated,” Cano says. “I felt a lot stronger and more confident, and I saw a side of myself I didn’t know I had.”

Find all of our coronavirus coverage here.

Read more from the Observer:

-

State Employees Criticize Texas’ Uneven Approach to Worker Safety Amid COVID-19: A slow, patchwork response to COVID-19 has jeopardized worker safety for some of Texas’ lowest-paid public employees.

-

COVID-19 Cases Now Tied to Meat Plants in Rural Texas Counties Wracked with Coronavirus: The outbreaks, which are being investigated by the state health agency, represent the first reported cases of the virus inside Texas meatpacking plants, and are in rural areas where medical resources are already stretched thin.

-

Spinning Their Wheels: Dallas’ paltry public transit system makes owning a car all but required. So as the metroplex booms, many low-income residents are shut out of jobs and services they need.