High-Wire Act

Laughter, fear and Trump at the Spanish-language circus on the Texas-Mexico border.

A version of this story ran in the April 2017 issue.

High-Wire Act

Laughter, fear and Trump at the Spanish-language circus.

by Daniel Blue Tyx

April 10, 2017

As I drove toward the small border city of Donna on a cold and misty February evening, the circus tent’s eight floodlight-topped spires glowed Oz-like in the distance. I parked my car in the free lot, property of a neighboring farm-implements dealer, and joined the throng of circus-goers following a path lined by purple flags mounted atop a wooden fence. On the other side was a line of motor homes. My imagination conjured up images of clowns and acrobats inside, applying makeup and readjusting sequined outfits with all the fidgety trepidation of opening night.

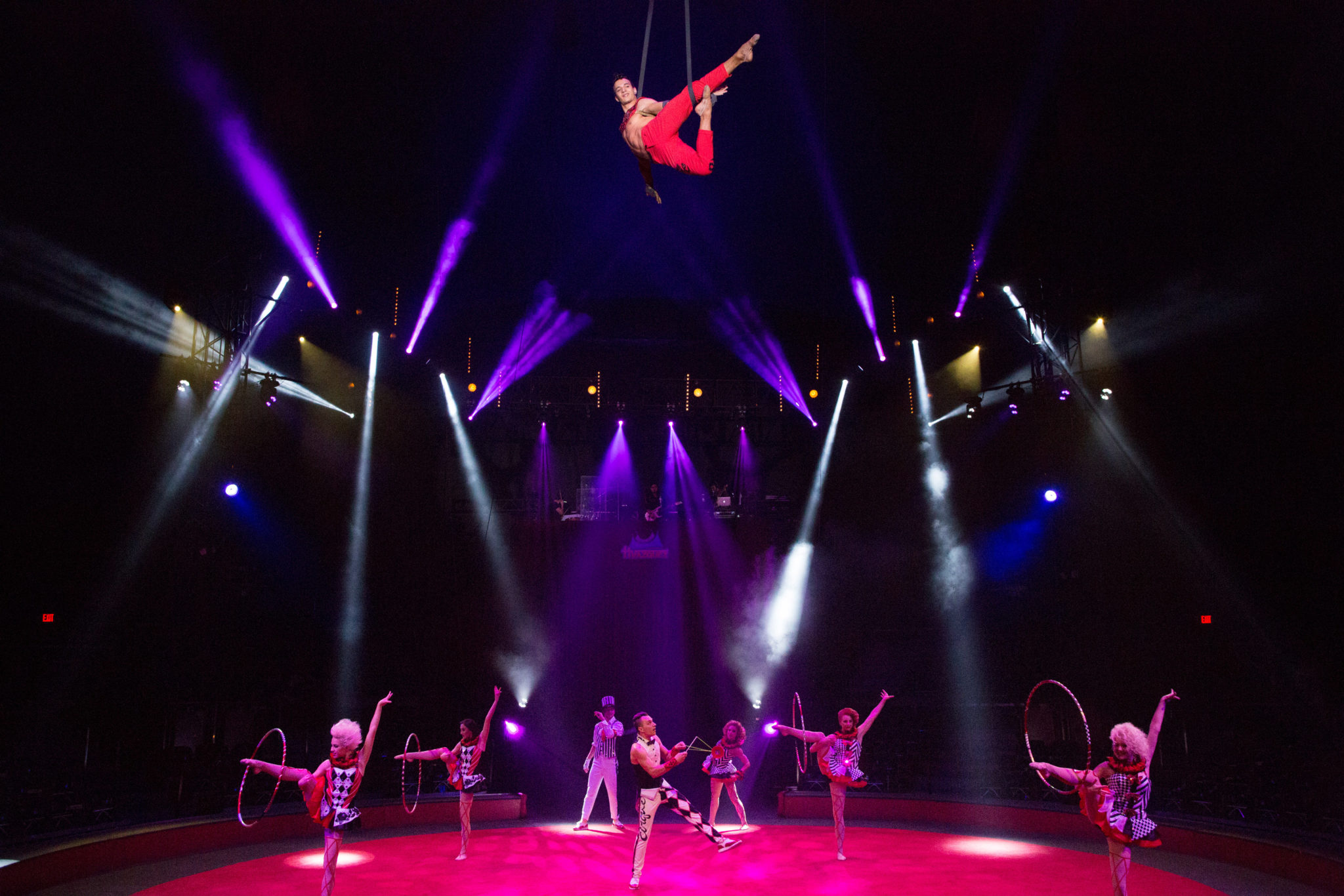

At the entrance, a tuxedoed little person greeted each customer with an individual “Bienvenidos.” When it was my turn, he didn’t miss a beat: “Welcome.” I found a seat halfway up the grandstand, next to an elementary school-aged girl who eyed me — the only Anglo in the crowd — with not-unfriendly curiosity. Purple-and-blue lights streamed from the catwalks, making the milieu feel more like a theater than a tent, though when I looked down through the bleachers, I saw grass still managing to grow.

Most of the audience, but not all, spoke in Spanish, as did the roving vendors proffering sugary raspas in neon light-up cups and popcorn drenched with hot sauce. Then the lights dimmed. A spotlight trained on a towering red-velvet curtain, from which emerged a young ringmaster, hardly more than a teenager. “¿Están listos?” he boomed, his youthful tenor rising in a P.T. Barnum imitation. The crowd roared “Sí” in assent as a longhaired electric guitar player on an elevated stage struck his first chord. “¡Comenzamos!”

This ceremonial opening marked 20 years since Circo Hermanos Vazquez, the nation’s only touring Spanish-language circus, came to the United States. What began as a tiny spinoff from a popular Mexican circus now encompasses 100 vehicles, 200 employees and what the Vazquez brothers say is the largest traveling circus tent in the Americas. But while it has grown exponentially, the circus also faces unprecedented challenges. Like all circuses, it must reckon with the imminent closing, in May, of Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey, “The Greatest Show on Earth” for 146 years. Unique to this circus, though, is a second challenge: widespread fear, among many members of its core audience, inspired by the election.

“Right now, we don’t know what’s going to happen,” Guillermo “Memo” Vazquez, one of five founding brothers, told me two weeks after opening night. Stout and gregarious, Memo was once the show’s ringmaster and now works as the artistic director. “We’re already seeing deportations. [Our audience] says, ‘We’re not going to the show today, because we don’t know what’s going to happen tomorrow.’ It’s affecting attendance.” As we spoke outside, Memo leaned against one of the enormous ropes supporting the tent. “One problem we have this year is Donald Trump,” he said. “The other is that in the mindset of the people, circus is dying because Ringling Bros. is closing. There’s no business, no animals, it’s dying.”

The Vazquez brothers are third-generation circus people. One grandfather was an acrobat, and his wife a circus poet, composing satirical verses that lampooned the political figures of her day. The grandfather on the other side sewed canvas circus tents by hand. Later, the brothers’ parents saved money to start their own circus in Mexico while working as a husband-wife acrobat act in the United States. The brothers worked in that circus from the time they were children until they started the second traveling unit in the United States.

For Memo, who as ringmaster once worked onstage with tigers, the issue of animals hits close to home. Ringling Bros. claims that attendance declined sharply after the circus stopped using elephants in response to public pressure and a growing number of state and local ordinances banning the use of wild animals in circuses. Similarly, the original Hermanos Vazquez circus in Mexico closed in 2014 after Mexico City passed such a ban, which was extended nationwide a year later. “Circus people love the animals,” he said. “We don’t have elephants and tigers so we don’t have the PETA people here. We have horses and dogs.” Circo Hermanos Vazquez USA once traveled with camels, zebras and tigers, but the circus began phasing out the use of wild animals in 2008. Most shows now include only horses and dogs, though the company occasionally hires independent contractors to exhibit wild animals in individual cities. (A PETA spokesperson told me that, though the organization would like to see animal-free circuses, the change is “a huge step in the right direction.”)

Memo’s younger brother Ramón, the circus’ co-owner and CFO, noted that many successful contemporary circuses, such as Cirque du Soleil, have scaled back the use of animal acts or eliminated them altogether. “In Mexico, there was a saying when I was a kid,” he told me. “The government was trying to encourage people to have less kids, so they said, ‘Pocos hijos, para darles mucho.’ Fewer kids, so you can give them more. We have less animals because we want to keep them in excellent condition.”

Meeting me in his office at the company’s Donna headquarters, which was decorated with family photos and a bookshelf divided between volumes on circus history and business, he emphasized that Hermanos Vazquez has adapted to changing circumstances. “When we brought the circus here, it wasn’t just crossing the border and we start to perform. We had to reinvent ourselves,” he said. At first, the brothers tried doing the show in English, then both languages, “but we had two groups of people uncomfortable instead of one feeling at home.” Eventually, the brothers settled on their current formula: 100 percent Spanish, and a tour of 11 cities with large Latino populations, including Dallas, Houston, Atlanta, New York and Chicago.

Ramón was cautious about predicting whether 2017 would be a down year. “We’re just at the beginning of the season,” he said, “and [Trump’s election] has taken us by surprise — everyone, I guess. Every city is different. So, it’s too soon to know.”

Still, Ramón and Memo agreed that the circus industry is in a tumultuous time. And they shared a sense of indignation that Feld Entertainment Inc., which in addition to Ringling Bros. owns productions ranging from monster trucks to Disney on Ice, was closing midseason, when it will be difficult for performers and roadies to latch on with another circus. “They are not circus people, you know?” Memo told me. “Here, for us, circus is the only thing we have. This is our lives. So, we want to keep trying, and trying, and we will die trying.”

In the excitement of opening night, the circus didn’t feel like it was dying. Though fear might be keeping some people home, within the friendly confines of the big top it was also palpable in ways I hadn’t expected. Not merely an escape, the circus became a theater wherein the audience’s private fears were played out in ways both subliminal and overt — often to hilarious, even cathartic, effect.

The first act was the Ukrainian troupe Bingo. Though most performers are Hispanic, the circus also recruits performers from other backgrounds, especially those like Bingo who have won awards at the Monte-Carlo International Circus Festival, the industry equivalent of the Oscars. The troupe’s most remarkable, and surreal, attribute was their costuming. While the house band launched into a driving heavy-metal anthem, a dancer shot out from behind the curtain in a tight-fitting Uncle Sam facsimile, followed by a devil-stick juggler outfitted as Satan himself. The rest of the entourage swarmed onstage in trippy diamond-patterned red-white-and-blue leotards, evoking court jesters. The underlying metaphor was subversive, heralding an entry into an alternate universe in which little was taboo, and nothing quite as it seemed.

Then came the clowns. Pedro Pedro, a heavyset, older clown with a sad visage and Charlie Chaplin bowler hat, played the opening refrain of the Mexican Hat Dance. Peter, much younger, joined him on stage with a faster, louder version of the same tune. The playful back-and-forth continued, until a third, middle-aged clown, Tin Tin, raced into the ring, decked out in a shimmering gold tuxedo. “¡Silencio!” he intoned, the effect amplified by white makeup applied to his lower lip in a permanent pout. With a violin in hand, Tin Tin demanded that he be the only clown onstage. “Bequietshutup!” he shouted, in comic English.

After a slapstick tussle, the bellicose Tin Tin shoved his fellow clowns back behind the curtain. But as he raised his violin, the rotund Pedro Pedro reappeared, now wearing an outrageously sequined rainbow-hued serape. The elder clown seized the microphone, leading the crowd in a singalong of “Cielito Lindo”; by the time he reached the chorus, it seemed the entire audience was singing until their lungs would burst. “¡Que vivan todos los latinos!” cried Pedro Pedro, in case the message wasn’t clear enough already.

“¡Que viva Donald Trump!” Tin Tin answered, his rejoinder met by a cacophony of boos. Taking the microphone, he was interrupted again, this time by young Peter, who stole the spotlight with an absurd hip-swiveling Backstreet Boys tune. As Tin Tin made one last vain attempt to impose silence, Pedro Pedro instigated a singsong chant heard in soccer stadiums when the crowd believes a player should be ejected. “Fuera, fuera.” The chant drowned out even Tin Tin’s amplified voice. Silenced, Tin Tin left the tent.

In real life, Pedro Campa is 67, his son Martín is 45 and his grandson Peter is 21. They hail from a line of five generations of musical clowns. I met them backstage after they’d finished filming a segment for a children’s television program. Martín and Peter wore T-shirts and jeans, their makeup the only vestige of their clown personas. Pedro was still in full costume, red-tipped prosthetic nose and all. When I asked about the Trump routine, the Campas laughed, then turned serious. “The first time I wore that serape, people actually started to cry,” Pedro said.

“We’re always looking for that point that everyone identifies with,” Peter continued. “Like Donald Trump. Like the songs we all know. It’s what connects people, and it’s what connects us to our audience.”

“This president is a showman,” Martín said. “He’s the president, but he’s a showman first. Everyone is watching to see, ‘What is he going to do?’”

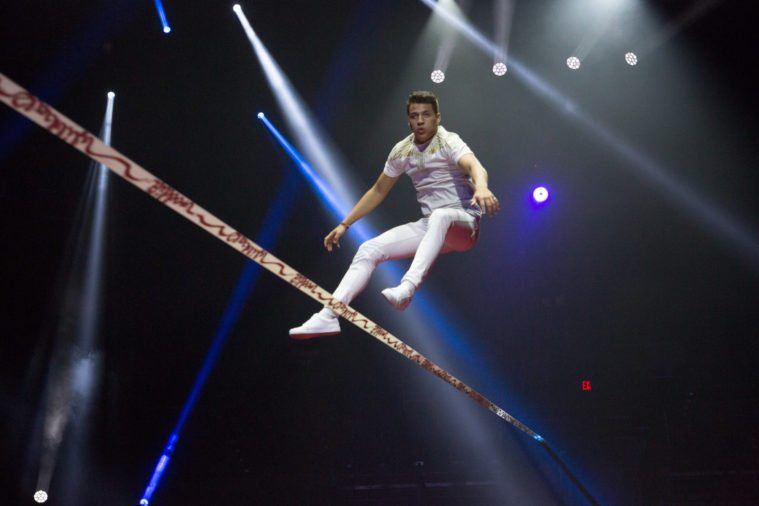

“The line between danger and humor — that tightrope, literally — is so much part of the essence of the circus experience,” University of Texas at Austin circus scholar Janet Davis told me. “Across time, [the circus] really calls into question what it means to be alive. But it also endures because it is adaptive to the zeitgeist of any particular time. … There’s this sense of cathartic solidarity.”

The most terrifying act, for me at least, was the trapeze. Near the conclusion of the first act, a young trapezist emerged in a sequined baby-blue leotard. With a dramatic flourish, she produced a red handkerchief and threaded it through a loop in her costume. She stepped onto the bar that had descended from the rafters; slowly, the two wires on either side began to pull her up again, some 60 feet in the air. After a few false starts, she let go of the ropes on either side of her, balancing with hands outstretched, first on two feet, then one.

She wore a safety harness, unlike many of the acrobats in the show. Yet never for a moment had I feared for the others’ safety, their muscular physiques and bravado — an earlier acrobat faked slip-ups for effect — inviting suspension of disbelief in the laws of physics. Perhaps it was her young age, or her slender frame, or her apparent tentativeness, or the agonizingly precise nature of her act, relying on minute acts of calibration rather than sheer strength, but I was genuinely afraid she might fall.

Later, I would learn that the trapeze artist was Carolina Vazquez, Ramón’s 16-year-old daughter. She told me that, though she’d practiced the act since she was a little girl, opening night was her first public performance. “Before I go into the ring, I’m extremely nervous,” she said. “My hands are sweating, my body is shaking. But the moment I step onto the bar, I forget all the pressure. I only concentrate on doing it: the trapeze.”

The trapeze is one of the most traditional acts in the circus, dreamed up by the French acrobat Jules Leótard, who lends his name to the costume, in the mid-1800s. Even with a safety harness, the danger is real. Two years ago, an experienced acrobat fell 25 feet at a Circo Hermanos Vasquez show when her safety harness slipped; she escaped serious injury. Carolina told me that she has fallen, twice, in practice. “It does hurt a lot because it’s tight around your ribs,” she said. “Now, I have the act more or less under control.”

“The line between danger and humor — that tightrope, literally — is so much part of the essence of the circus experience.”

In addition to Carolina, Ramón’s son Jan is performing in this year’s show as a slackline walker. “This is a business of tradition,” Ramón said. “You cannot go to the university to learn circus. You have to teach it to the next generation.” Jan, who was home-schooled with his sister, recently graduated from high school; Carolina will soon follow. “If at some point they want to do something different, I’ll be OK with that,” Ramón told me. “They are at the stage when they have to decide.”

As the youngest members of the Vazquez family ponder their futures, they must also weigh the future of the circus itself. Jan responded with teenage nonchalance when I inquired about his plans. “For now, I like what I’m doing, but tomorrow, who knows?” he said. “Maybe someday I’ll be a juggler, or a clown.”

Carolina, though, expressed a stronger sense of obligation. “It’s an honor for me to be part of this circus family, and also a big responsibility,” she said.

For the grand finale of Carolina’s act, she removed the handkerchief from her leotard and folded it over the bar. Then, she began leaning back and forth, like a child pumping on a swing, until the trapeze was a pendulum tracing an arc from one end of the tent to the other. The idea, it became clear as she lowered herself onto her knees, was to catch the handkerchief in her mouth on one of the upswings. Afterward, she explained to me that her great-aunt had performed the same act, and it was now disappearing from the circus; the few trapeze artists she knew who still did it were all men.

The music stopped, for the first and only time in the show, the total silence its own kind of soundtrack. Carolina’s arms extended outward from her body like a bird’s wings, but she missed on her first attempt. She missed on the second and third attempts, too.

On the fourth attempt, she grasped the handkerchief between her teeth, but she plummeted from her perch, catching herself by her fingers at the last moment. As the band began playing, the trapeze was gently lowered. We took a moment to recover from what we’d seen, reminding ourselves that, after all, this was just part of the show. It wasn’t until she was safely on the ground that we all began to cheer.

This article appears in the April 2017 issue of the Texas Observer. Read more from the issue or become a member now to see our reporting before it’s published online.