Learning Arabic in Houston, Inshallah

Despite an angry outcry from far-right protesters, Houston is embracing an Arabic immersion school that educators hope may give students an edge.

Except for the angry protesters, the first day of school at the Arabic Immersion Magnet School in Houston in late August was a joyous occasion. The school welcomed its inaugural class of 88 kindergartners and 44 pre-kindergartners with an assembly in the cafeteria.

The kids wore their school uniforms, green-and-white polo shirts embossed with the school’s calligraphic logo. They learned their new school song. They recited the Pledge of Allegiance and the Texas Pledge. Alicia Kahn, whose 5-year-old daughter Maiara attends the school, described the mood as “positive and upbeat.” Outside, though, she said it was “mayhem.”

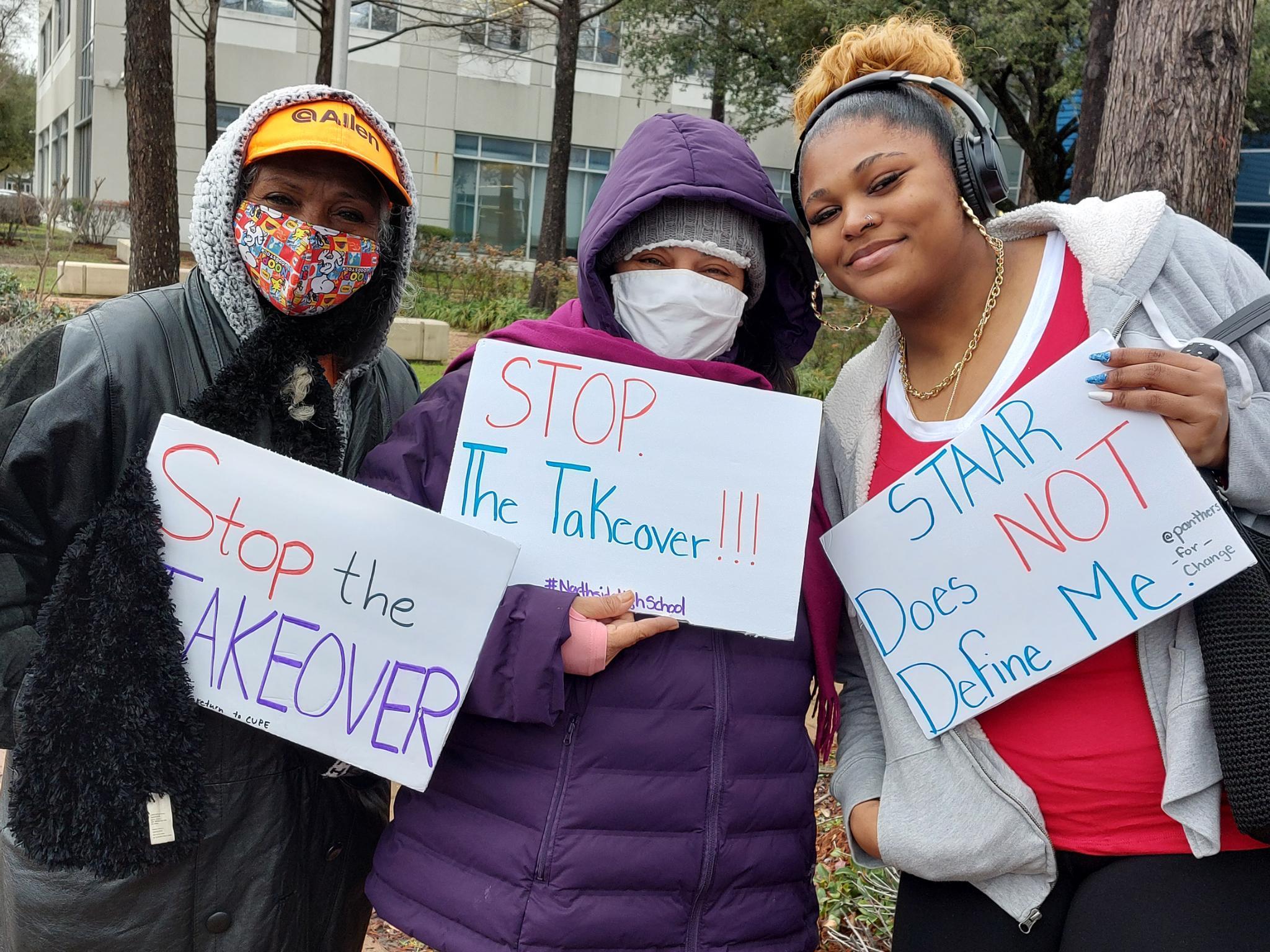

A small crowd organized by the anti-immigrant group Stop the Magnet had gathered near the school entrance for the “Houston Patriots Protest.” Waving signs and American flags, the protesters shouted their message at entering parents. “Forcing a child to have to speak Arabic should be against the law,” one protester yelled at a woman pushing a stroller with a kindergarten-age kid in tow. Another protester held a sign reading, “Everything I ever cared to know about Islam was taught to me by Muslims on 9-11-2001.”

Parents and faculty were not entirely surprised by the rude welcome. At a May 2015 HISD board meeting, they got a dose of what some people think of the country’s first public Arabic immersion school. It wasn’t pretty.

About a dozen individuals took to the podium to give mini-lectures on the dangers of Islam and the need to prioritize English-language education. “I’m a proud monolingual American citizen,” said a middle-aged man, Phil Cady, reading a prepared speech from his cellphone. “I believe it is wrong to teach babies Arabic or any other language before their reading and writing in English is proficient.” Elizabeth Theiss, founder of Stop the Magnet, directed her anger at the board: “It’s a disgrace, all of you are anti-American.”

Though the school, which plans to expand to fifth grade, hasn’t received any direct threats, administrators aren’t taking any chances, employing a security guard to keep watch during school hours.

Parents are taken aback by the anger and the protesters’ apparent belief that the school is part of an attempt to establish a “multicultural caliphate.”

“That is one thing that’s scary,” said Kahn, “because you see these sort of American fundamentalists who are very anti-anything that has anything to do with the Middle East. … It’s really a shame that that needs to be a part of the conversation.”

But Kate Adams, the principal of the Arabic Immersion Magnet School (AIMS), doesn’t dwell on the vitriol.

“Anytime you’re doing something that’s trailblazing and different” there will be critics, she said. “Even in a regular plain-old vanilla school.” And AIMS is anything but vanilla — something Houston has largely embraced.

The majority of students are Texans with no ties to the Middle East or Arabic language.

Houston is the ideal city for a school like AIMS, said Emran El-Badawi, the director of the University of Houston’s Arab Studies program. Arabic is the second-most common foreign language spoken at home in HISD, and the city is home to the country’s fifth largest Arab population. “This is the economic and cultural golden age of Houston that we’re living in right now,” said Badawi, who also serves on the AIMS board, “and that subsumes everything — oil, gas, medical, education.”

One might argue that Houston is in an anxious moment — given the recent layoffs at Chevron, Halliburton and other corporate giants — but the prospects certainly look bright for Arabic education. HISD has placed a premium on giving students what it calls a “global education,” even opening an Office of Global Education that pushes its immersion and dual language schools. In a city that rises and falls with the global markets, learning a second language like Arabic, educators hope, may give students an edge in an uncertain future.

If you want to learn a language, immersion is the way to do it — a principle that AIMS embraces.

Unlike an Arabic-language class or a bilingual school, math and science courses at AIMS are strictly in Arabic. (Social studies and English are taught in English.) The teacher only speaks Arabic to the students — coupled with a lot of gesturing and facial expressions — and, as the students pick up vocabulary, they start talking back.

Some parents ask if their child will be fluent in Arabic by the end of third grade. “And I’m like, well, no, but your child is not going to be fluent in English by the end of third grade,” said Principal Adams. “The other thing I remind parents of: These are not adults who are learning Arabic; these are children who are coming in and learning for the first time in a school setting.”

HISD Superintendent Terry Grier first publicly announced the possibility of an Arabic school in February 2014. The district had successfully opened a Mandarin Chinese immersion school in 2012, as well as several Spanish immersion schools. In November 2014, the nine members of the HISD board unanimously voted to approve the school.

“Within two years this entire thing went from an idea to a reality,” said Badawi.

The school, located in a renovated elementary school on a busy street in the historic Houston Heights neighborhood, is full of special touches. Phrases in both Arabic and English are painted on the walls of the main hallway, listing the qualities of an HISD “Global Graduate”: Critical Thinker, Skilled Communicator, Leader. Each classroom is equipped with interactive smart tables and iPads, made possible by a $130,000 donation from Aramco, whose parent company is the Saudi national oil company. Just down the hallway is a technology lab fully outfitted with new PCs.

No parents I spoke with expressed misgivings about the school’s corporate funding. Many of the parents work in the energy industry, and Adams pitches the association as a bonus on the school website: “While it may seem far away, learning Arabic will help your children gain jobs in the oil and gas industry, State Department, and many multinational corporations,” she writes.

Amy Crouser describes her discovery of AIMS as a “kind of random thing.” Horn Elementary in Bellaire was her top choice for her 5-year-old son Van, but when the school informed her that all spots were filled, she began her hunt for a new school on the HISD magnet website, starting at the letter “A.” She was intrigued by the idea of an Arabic school but also a little uneasy. “My son doesn’t speak any Arabic and I didn’t want him to be thrown into a mix where he would fall behind or feel out of place,” she said. Amy reached out to Adams and received a prompt response that impressed her. She applied immediately.

Amy has no family ties to the Middle East — she is from Lafayette, Louisiana — but Van’s father is Lebanese and lives in Lebanon. Van only “has contact with him a few days out of the year,” Amy writes in an email, continuing, “In the day-to-day life, Van is just a Texas boy who calls pita bread a tortilla!”

I ask if Van’s attending the school is about connecting to his heritage. “It sounds good to say, but I don’t really feel that way,” she said. She believes her son “probably should be familiar with his past,” but that she really just wants him to be bilingual. She’s taught Van his numbers in Arabic and he’ll utter the occasional Arabic phrase. “To him, they’re just words. I don’t think he even thinks about it too much as language,” she said.

By Adams’ estimate, only 15 to 20 percent of the 132 students have been previously exposed to Arabic and an even smaller percentage speak Arabic at home. The majority of students are Texans with no ties to the Middle East or Arabic language. The student body is almost equally split among white, black and Hispanic kids. Enrollment is open to any student in Houston — but the competition is stiff.

AIMS received over 450 applications for its 132 seats. Mahassen Ballouli, the school’s magnet coordinator, still gets calls from parents checking on their wait-list status, even as the school year begins.

Bellaire has offered Arabic as a foreign language since 1986, making it possibly the longest running K-12 public Arabic program in Texas.

Ballouli recruits for AIMS throughout the year. She’ll visit Head Start programs and attend HISD recruiting events to get the word out. Her goal is to “make sure the school represents the diversity of Houston,” but Arabic is not always the easiest sell. “[Parents] kind of give me this puzzled look,” Ballouli said, “and they’ll come over and ask, ‘Why Arabic?’” She explains to them “all the perks to learning a second language in general — increased cognitive ability and critical thinking skills and improved test scores.”

Amanda O’Leary, the magnet coordinator at Bellaire High School’s World Languages Program, uses a similar approach when she recruits at Houston junior highs, encouraging students to study one of the 11 languages on offer at Bellaire, including Arabic. O’Leary presents Arabic as a path to a six-figure corporate salary or a government job. That appeals to some of the more ambitious kids. “The ones that are talking about the Ivy League colleges, the ones who really know what they’re about, they’ve heard of Arabic before and they’re interested,” she said. Bellaire’s language program received over 2,000 applications in 2013-2014 and took just 137 students.

Bellaire has offered Arabic as a foreign language since 1986, making it possibly the longest running K-12 public Arabic program in Texas. That’s impressive because sustaining such a program has proven to be a difficult task. In the 2013-2014 school year, 13 public schools in Texas offered Arabic classes to at least 424 students, an increase of 124 students and three schools from the previous year. But the growth has been uneven, at best. Over the past decade, K-12 Arabic programs have launched in unexpected places such as Waxahachie and Mercedes in the Rio Grande Valley only to close shortly thereafter.

Usually the reasons for failure are mundane — lack of enrollment or staffing issues — but occasionally Arabic programs attract the suspicions of the conspiracy-prone.

In 2011, Mansfield ISD attempted to offer Arabic as a foreign language in its elementary and middle schools. False rumors spread among parents that it was “mandatory.” The school had accepted a $1.3 million grant from the federal government under the Foreign Language Assistance Program, which had received a huge boost in funding, about $24 million, through the Bush-era National Security Language Initiative (NSLI).

After 9/11, calls to increase the number of Arabic speakers in the military, intelligence and diplomatic communities had reached a fever pitch. “We’re reduced to putting 800 numbers on the TV screen asking for people who speak Arabic,” the New York Times quoted one public policy expert as saying in 2004. Pundits on the left and right called for a visionary nationwide program to boost language learning, something akin to Eisenhower’s “Sputnik moment.” The NSLI was supposed to be such a program. But folks in Mansfield apparently didn’t get the message.

At public forums, parents expressed concern that the cultural component of the curriculum meant indoctrinating their children with Islam. Lawmakers helped stoke their fears. State Representative Dan Flynn described the program as “an attempt by the federal government to sensitize our children to this culture.” Due to the public outcry, Mansfield ISD announced it was going to resubmit its grant proposal with changes to appease the community. The Department of Education denied the revised application for unknown reasons. In 2012, Congress defunded the program.

After 9/11, calls to increase the number of Arabic speakers in the military, intelligence and diplomatic communities had reached a fever pitch.

The old fears came roaring back at the Houston ISD board meeting in May.

Stop the Magnet supporters were incensed that AIMS had accepted funding from the Qatar Foundation International, a nonprofit established in 2009 that’s funded by the Qatari government. On its website, the foundation claims it is “dedicated to connecting cultures and advancing global citizenship through education.” The foundation has helped fund at least 19 K-12 Arabic programs in the United States, as well as a few in Canada and Brazil. The nonprofit also provides mentorships, trainings and fellowships for Arabic teachers in the United States.

But Stop the Magnet’s opposition barely registered in diverse Houston. On the second day of school at AIMS, a group of neighbors gathered outside the school to offer a more welcoming message to students, holding signs reading, “America was built on diversity!”

The scene “brought tears” to Alicia’s eyes. “OK, not everybody sucks,” she told herself. Alicia has worked as a biostratigrapher at Chevron for almost a decade, examining fossils. She knows a little bit of Arabic, gleaned from traveling in Egypt after college and speaks wistfully about her daughter learning about foreign cultures.

“I love her coming home and saying stuff in different languages. It’s so neat and so mind-opening,” she said. Maiara has attended a Spanish immersion camp and speaks some Portuguese. (Her father is Brazilian.) Arabic, however, was “completely alien” to her before her first day at AIMS. Now, Alicia said, Maiara is already counting in Arabic and saying her colors.

Alicia doesn’t expect some kind of “overwhelming transformation” in her daughter after attending AIMS, though she does hope she feels a deeper connection to the world.

“I think even just knowing or being exposed to another language opens up your world,” she said. “Even if you don’t go to Egypt, Syria or Lebanon, though hopefully you would, even walking on the street, you go to Phoenicia market and you hear Arabic, and all of a sudden your context changes.”