How a Tiny ‘Startup’ in Houston ISD is Reinventing Discipline for Thousands of Students

The new school year marks a milestone in Houston ISD: the end of suspensions for students in grades two and under. Following similar policies in other big urban districts, HISD is ending a practice that disproportionately harms students of color and disabled students. Research suggests that suspensions can be particularly harmful to young students.

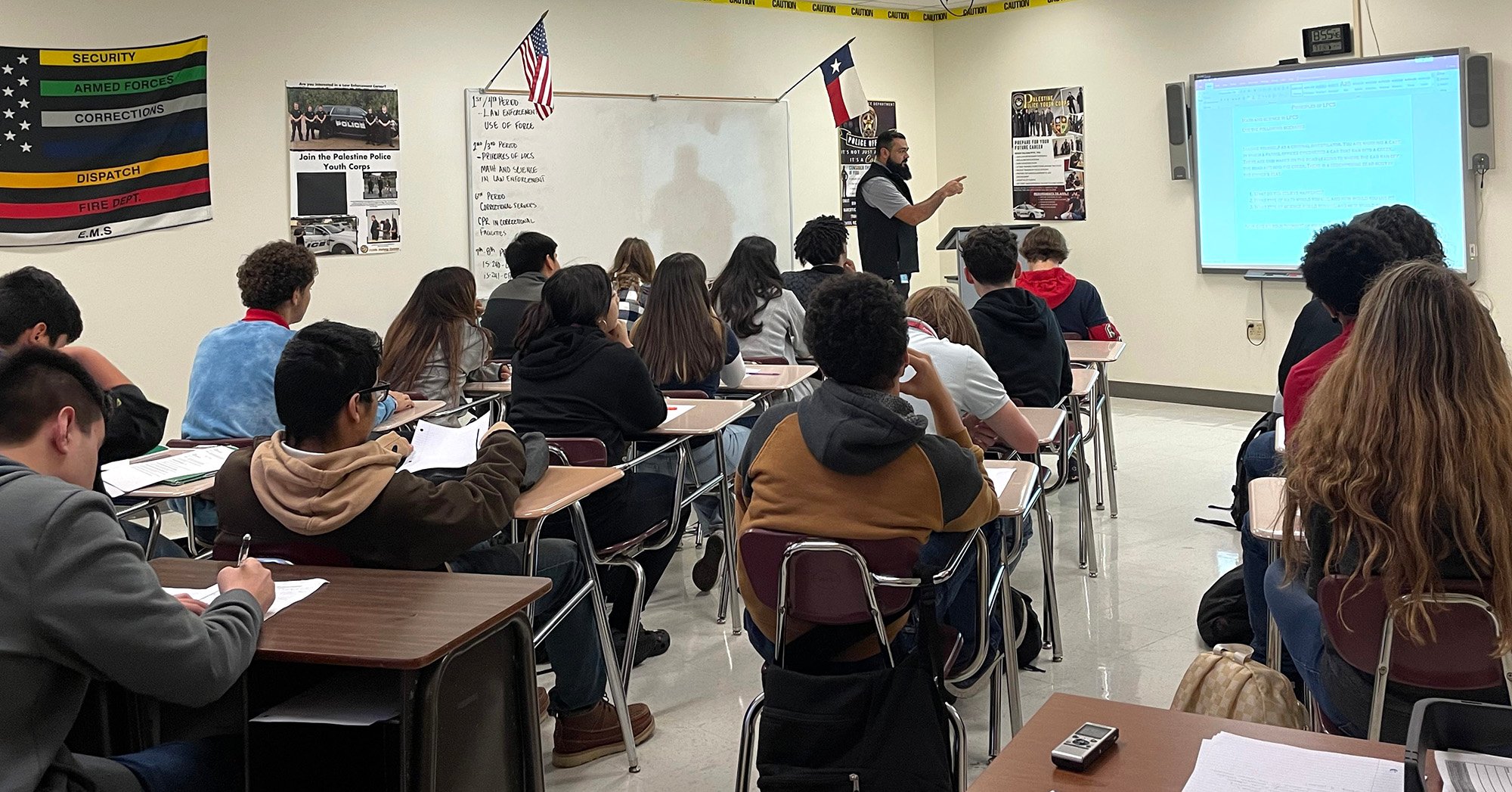

As in El Paso ISD, the other urban Texas district that’s making the change this year, the ban in HISD is part of a broader effort to retool its approach to classroom discipline. By banning suspensions for young kids, administrators are taking away one strategy that teachers relied on to keep their classrooms running smoothly, even though suspensions tend to increase students’ odds of landing in the criminal justice system. So what are teachers supposed to do now?

To answer that question, the largest school district in Texas is relying on its new Office of Social and Emotional Learning, staffed with behavior coaches and psychologists. Speaking by cell phone because his office doesn’t have landline phones yet, director Michael Webb told me there’s an enthusiastic startup culture at the division, even though it exists within Houston’s mammoth school district bureaucracy.

Implementing the new suspension ban is just one of a few jobs for his team, which is modeled on a program in Austin ISD. Webb said that his office also hopes to make discipline more racially equitable for HISD students of all ages. True to HISD’s data-driven traditions, his office has even set targets for the new year.

In the last year in HISD, African-American students accounted for about one quarter of the total enrollment, but nearly half of the district’s suspensions. Webb wants to see that difference close by at least 10 percent in the coming year. Webb also hopes to see a 15 percent decrease in the number of students suspended this year — in the 2015-16 school year, more than 13,100 students were suspended at least once — and a reduction in the number of students sent to disciplinary alternative campuses. Last year the district pushed almost 2,600 students from their school into a disciplinary campus.

“The ban on suspensions is going to help in the numbers,” Webb said, “but my concern is what are we doing if we’re not suspending them? We don’t want them sitting in the principal’s office.”

One team within Webb’s new office handles suspensions, to make sure students of any age are only being removed from class where the district’s discipline code allows it. The other teams include crisis intervention experts — ready to jump in to help students with grief or trauma — and psychologists and newly hired school psychologists who’ll spend the year working at one or two schools.

The team with the broadest reach will handle training teachers in a model called Positive Behavioral Intervention and Supports, the same new approach El Paso ISD is embracing for its discipline program, which encourages setting clear expectations for students before discipline problems arise. Webb said the district has paid for staff at 68 schools to get that training so far from a company called Safe and Civil Schools. He hopes to reach 100 schools by the end of the year.

Webb said his staff will spend the bulk of their time working with a few campuses most in need of reworking their discipline systems, while leaving some other campuses mostly alone. “If things are working,” Webb said, “the belief here is that’s how you get your autonomy.”

There’s a risk of being perceived as an interloper, Webb said. Some school principals haven’t been completely enthused about the new training. He hopes that the program’s ultimate purpose, to bring greater racial equity to classroom discipline, will win them over.

“It’s like literacy — who’s against literacy? We call it a ‘sell,’ but it’s really just showing the value of what we can provide.”

[To read more Observer coverage about school discipline and the school-to-prison pipeline, click here.]