Houston ISD Could End Suspensions for Young Students

New report shows disparities in school discipline are more pronounced for kids in pre-kindergarten through fifth grade.

Update, November 13: The Houston ISD board removed the ban on suspensions before approving a policy Thursday night that says suspension should be used only as a last resort. The policy approved by board members would also require training in classroom discipline strategies beyond removing students from class. The Houston Chronicle has more.

Original story:

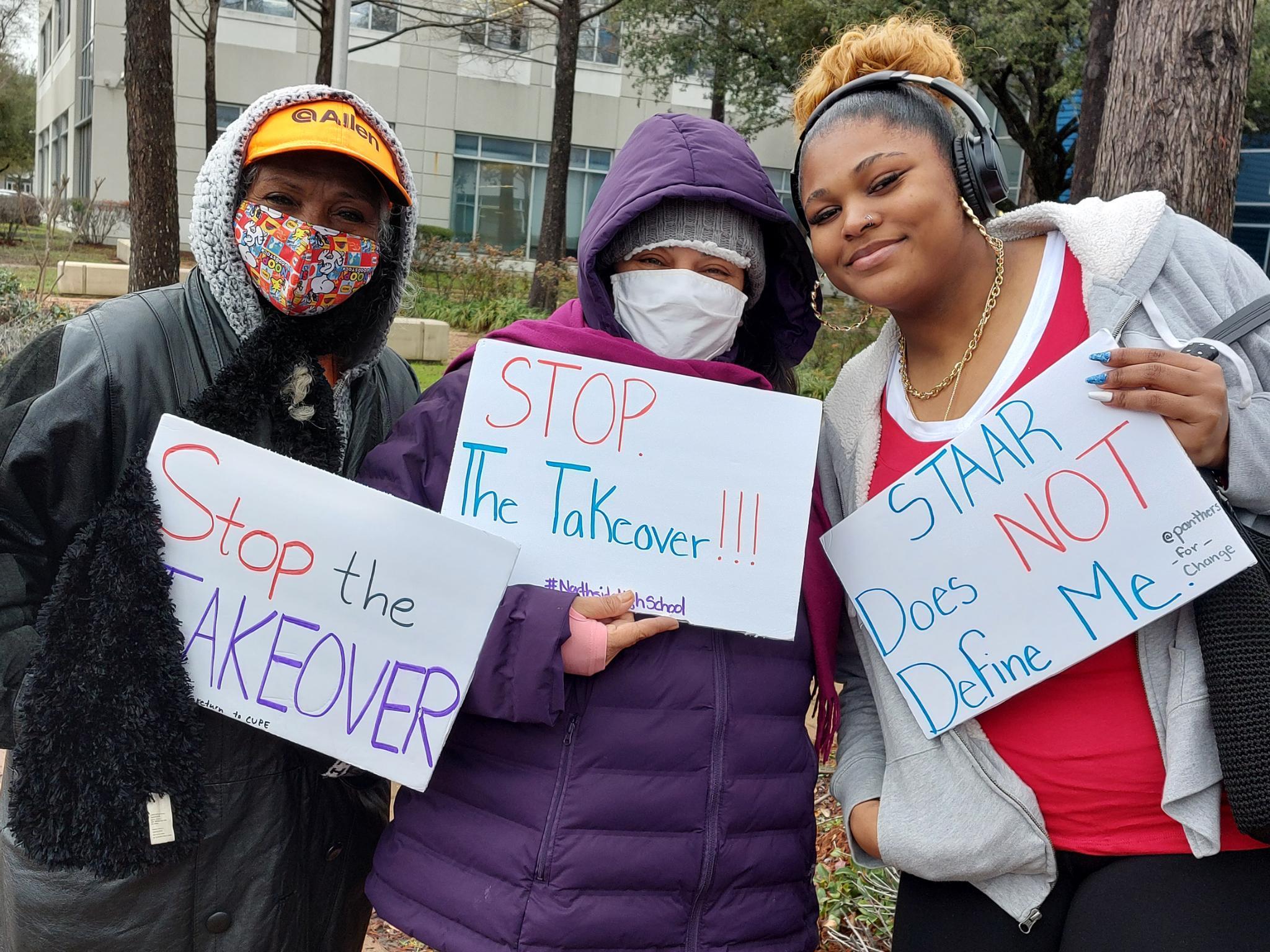

School discipline, the way most schools do it, is unfair. We already know that, in particular, black students and students who receive special education services are suspended and expelled at disproportionate rates.

And according to a report released Tuesday by the nonprofit Texas Appleseed, those disparities are even greater among the youngest students. While black students account for 13 percent of the population of elementary students in Texas, they account for 42 percent of the pre-kindergarten through fifth-graders who are given out-of-school suspension. The 9 percent of elementary students who get special education services in pre-K through fifth grade account for 22 percent of the suspensions.

“That is much more extreme than you would see at other grade levels,” says Morgan Craven, who directs Texas Appleseed’s school-to-prison pipeline project. Craven says the statewide numbers — which are collected by the Texas Education Agency but aren’t readily available on a grade-by-grade basis — mirror national trends that have prompted some states and school systems around the country to ban or limit suspensions for their youngest students.

Craven says she doesn’t know of a district in Texas that’s done so yet, but a vote by Houston ISD school board this month could make Texas’ largest school district the first with a ban on suspending young students. The proposal in Houston, which the board could approve on November 12, would ban suspensions for students in pre-K through the second grade, and allow suspensions of third through fifth-graders “as a last resort.” (State-mandated suspensions and expulsions — for violent behavior or, say, bringing a gun to school — would remain in place.)

Annvi Utter, an officer in Houston ISD’s student support services division, said the new policy would be a way to start changing the way schools approach classroom discipline, and move away from the zero-tolerance approach that schools in Houston, like the rest of the country, have relied on for decades. Utter says that Houston’s discipline disparities were especially troubling when it came to suspensions in the earliest grades, pre-K through second.

“We looked at our data, and basically 70 percent of these kids are black boys,” Utter says. A handful students tended to draw one suspension after another. “We’re not changing their behavior, we’re just putting a band-aid on it,” she says. “Principals agree that, yes, we are putting these kids at risk of dropping out. Teachers feel the same way but they don’t know what else to do. So the question is, what is the support you’re going to provide us?”

Should the board approve the new policy, Utter would help schools train teachers in new approaches that encourage positive behavior instead. (She says the district would provide training in a model called Safe and Civil Schools, but principals would be free to pick another one.)

“I think this is huge,” Craven says. “If other school districts could do the same, that would be really important.”

Houston ISD schools handed out more than 10,000 suspensions to pre-K through fifth-grade students in 2013-14, according to the Texas Appleseed report — more than all but neighboring Cypress-Fairbanks ISD. Craven hopes that Houston’s example becomes a model for other districts too, and even an inspiration to change state law.

Seeing black students or kids with special education plans getting disciplined more often informs their developing sense, Craven says, of “who is deserving of punishment and who is not.”

Repeat suspensions are especially dangerous, Craven says — young students who get branded as troublemakers tend to hold on to that self-image with them as they grow. The disparities are dangerous for other kids in the classroom too: seeing black students or kids with special education plans getting disciplined more often informs their developing sense, Craven says, of “who is deserving of punishment and who is not.”

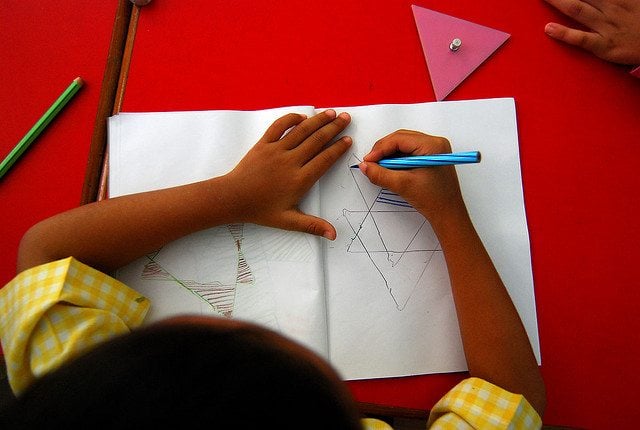

Ending suspensions for the youngest grades, Craven says, requires a shift in school culture, to give teachers new tools to plan for and respond to disruptive students. Texas Appleseed’s report recommends three models to help drive the change: Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports, restorative discipline, and social-emotional learning. Kicking a student out of class may seem a quicker solution in the moment, but Craven says research-based approaches like these help teachers to address the roots of a student’s behavior.

“It does take some time, but I think it is absolutely worth it in the long run,” Craven says. “Somebody that is in the education field, I’m sure, wants to do what’s right for kids, and this is a very clear right and wrong.”