Rarely has a loss been seen as such a win. Beto O’Rourke came closer to winning a statewide race in Texas than any Democrat in a generation. Now, the party apparatchiks have come calling to see if he has any plans on February 3, 2020 — the day of Iowa’s Democratic presidential caucuses.

Amid the frenzy to track every “Will He or Won’t He?” twist and turn, it’s worth taking a second to consider just how Beto managed to lose so well. Yes, he had the elusive political “it” factor. But his popularity would have been just hype without a way to harness it.

One of the least understood aspects of O’Rourke’s campaign was the audacious and experimental organizing model behind “Betomania.”

Ted Cruz may have been wrong when he claimed that O’Rourke is a socialist like Bernie Sanders. But when it came to the task of turning enthusiasm into votes, Beto looked to Bernie’s insurgent 2016 presidential bid — a breeding ground for digital organizing experimentation. O’Rourke relied on the top architects of Sanders’s campaign to help with everything from digital advertising and small-donor fundraising to, perhaps most importantly, building a grassroots ground game.

From the beginning of his campaign, O’Rourke took big risks. He swore off consultants, PACs and the Democratic Party playbook. But that approach didn’t come out of nowhere. O’Rourke came up in El Paso politics embracing a DIY style that helped him oust an entrenched Democratic congressional incumbent in 2012. “Part of our DNA is: if you’re not at the doors, you’re not winning a race,” Susie Byrd, O’Rourke’s longtime friend and former campaign manager, told the Observer.

But the 16th Congressional District is an isolated outpost, several hundred miles of desert and a time zone away from Texas’ other population centers. If Beto wanted to go big for a Senate race in a huge and complex state, he would need an infrastructure to match.

O’Rourke needed to build an operation that could reach an unprecedented number of voters in Texas, more than 5 million — many of them first time or unlikely voters. To do that with a traditional campaign structure, O’Rourke would’ve had to pay thousands of staffers. David Wysong, who left his job as O’Rourke’s chief of staff in Washington, D.C., to guide the campaign’s strategy, wanted an infrastructure that took the best elements of Barack Obama and Bernie Sanders’ campaigns and melded it with the El Paso spirit.

“All the energy Beto was feeling [on the road], he wanted people to have as much control over putting that energy to work,” Wysong told the Observer. “Most campaigns, it’s like, ‘Hey, hang out, we’ll talk to you six months from now when we’re ready to put you to work.’”

So he shopped around for something — and someone — that could make that happen. To understand what Beto built, you need to understand what Bernie built. And to do that, you need to know who Becky Bond is.

A Californian with short, silver-streaked hair and and dark-rimmed glasses, Bond is something of a legend in progressive organizing circles.

As a senior adviser on Sanders’ presidential campaign, Bond was part of a small team scrambling to figure out a way to channel unexpected enthusiasm for Bernie into a self-organizing grassroots machine. Initially, Sanders was running a traditional campaign focused on doing well in states with early primaries, such as Iowa. The Vermont socialist had no infrastructure elsewhere. But as the Bernie bandwagon grew, he amassed volunteers looking for something to do in nearly every state. It would have been a disaster for the campaign to let that energy dissipate.

The solution was “distributed organizing,” as they dubbed it. With this, Bernie’s organizers began giving volunteers all the tools they needed to scale up the campaign, even in places where they previously had no presence. Organizers flew around the country holding “barnstorming” meetings to recruit and train volunteers to run their own phone bank, text and block-walk operations. That was one of the most revolutionary things about Bernie’s campaign and it became a cornerstone of O’Rourke’s.

It was a stark departure from the highly professionalized campaigns that made a fetish of Big Data, mining terabytes of information to help slice and dice the electorate. Bond saw the traditional approach as a dangerous strategy that incentivized a path to “50 percent of the vote plus one” and played a big part in Clinton’s loss to Trump.

“The big data strategy is where essentially you hire a bunch of data consultants to run a bunch of models to find out, ‘What is the smallest number of people you can talk to and win? Who are those people and what do they care about?’” Bond said in a 2017 interview. “We need to talk to everybody.”

Since 2016, the core Bernie organizing team has used their expertise to sow the seeds of the distributed organizing model. Bond has been everywhere — helping organize in the wake of the Women’s March, launching a group called Knock Every Door, advising organizations like the ACLU on how to launch distributed field programs and starting a PAC to elect progressive district attorneys like Larry Krasner in Philadelphia.

But it was Texas that presented the perfect opportunity to try something really big. The state is huge, diverse and has stubbornly low voter turnout that helps keep Republicans in power. “She took what she learned from and built on Bernie’s campaign and brought it to Beto’s campaign,” said Winnie Wong, a progressive activist from New York.

After 2016, Bond had teamed up with Zack Malitz, a protégé of hers and a twentysomething Austin native who had steered Bernie’s digital efforts in Texas. In late 2017, when the O’Rourke campaign was still getting its bearings and Beto was still a relatively obscure novelty, Bond and Malitz pitched Wysong, the campaign strategist, on their vision for big Texas organizing. He liked what he heard and ran it by O’Rourke, who signed off on the plan as the new year approached.

Malitz was hired on as the field director, charged with plugging Beto’s grassroots into the campaign’s infrastructure. The field team’s hivemind, a team of promising young organizers who had honed their chops on Bernie’s campaign and progressive outfits, operated out of the campaign’s Austin headquarters, an office next to an H&R Block in a strip mall.

At first, the campaign dedicated much of its volunteer muscle to blasting a massive list of voters with phone calls and texts. Though the persistent tactics were grating to supporters and opponents alike — Cruz even said he was contacted by Beto volunteers a few times — the campaign was confident that casting a wide net and following it up with intensive outreach would pay off.

Malitz helped build an open-sourced digital toolkit for volunteers. Expanding on techniques pioneered during Bernie’s campaign, that system empowered volunteers to do peer-to-peer texting, auto-dial phone banking and door-knocking all on their own time and with just a few clicks on a smartphone. Like Uber, but for grassroots organizing.

On November 4, its most prolific door-knock day, the campaign was hitting 340 doors a minute.

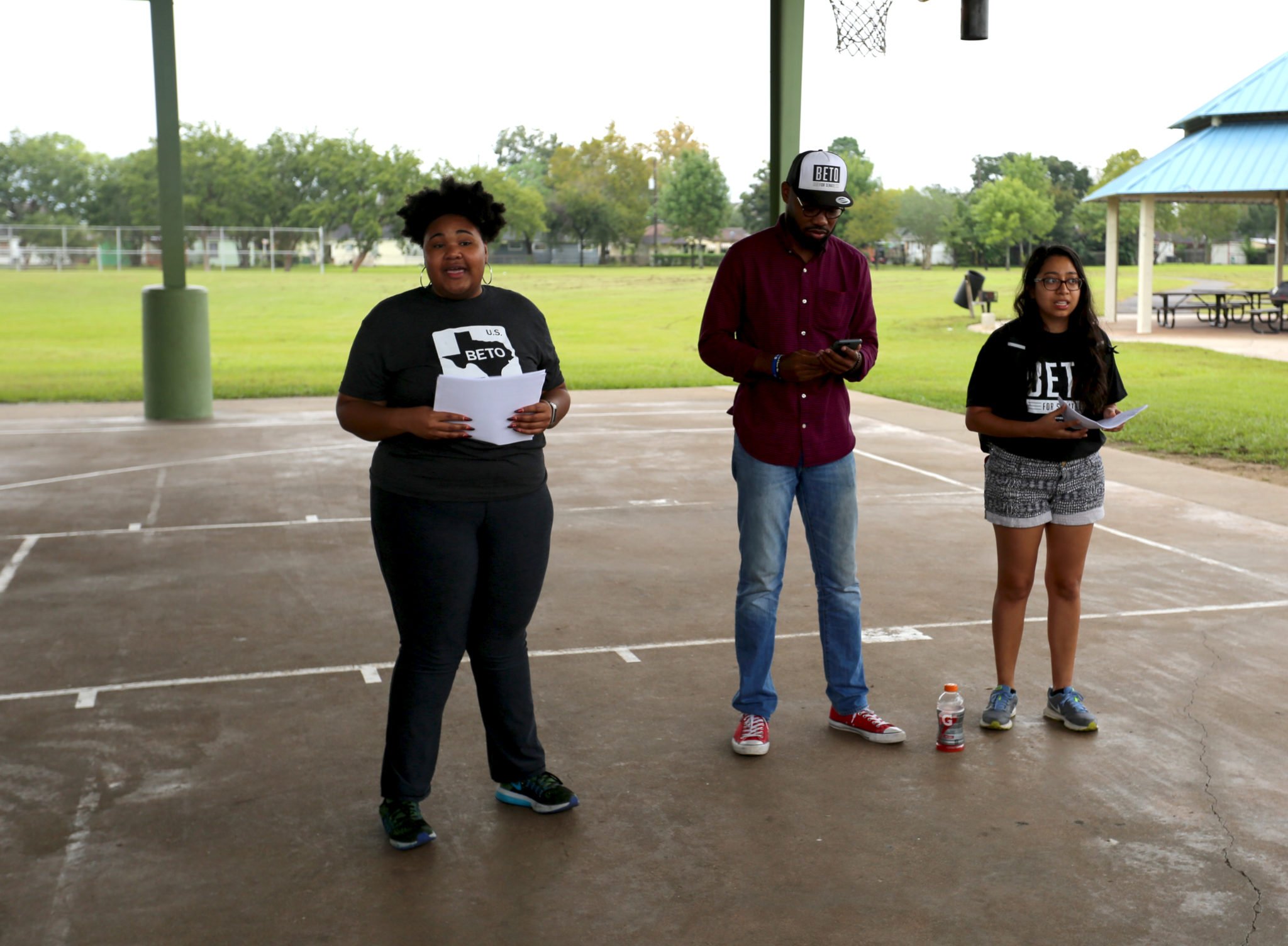

In late August, as the campaign shifted into get-out-the-vote mode, they released a “Plan to Win” detailing exactly how they sought to pull off an upset. The task was huge: mobilizing more than 5 million people identified as supporters. Over the next several weeks, staffers held dozens of organizing meetings around the state, training volunteers on what they had dubbed “the largest GOTV effort in Texas history.”

The most effective way to get those 5 million supporters to vote, the campaign believed, was to talk to them face to face. O’Rourke’s record fundraising numbers helped him hire close to 1,000 field organizers and open a dozen field offices. But a paid program would never be enough. The goal was to hit 3.6 million doors, requiring an estimated 72,000 canvassing shifts. Beto could only do that with an army of volunteers.

To scale up the GOTV effort, Beto needed his most avid supporters to open “pop-up” offices to serve as hyper-local hubs where volunteers could get trained and begin block-walking. Volunteers ultimately opened more than 725 pop-up offices around Texas — even Bernie’s campaign wasn’t able to set up such a local structure on a large scale.

The pop-ups were staffed by people like retired nurse Christine Bowman. On the last weekend of October, she gave me a tour of her riverfront home in deep-red Llano County, which she had transformed into a makeshift campaign office, complete with clipboards, literature and Beto’s Facebook livestreams playing on her mounted big-screen TV. A few minutes later, Charla Hays, one of the only other volunteers in the area, showed up for a block-walking shift. Hays had taken leave from her job as a traveling nurse so she could volunteer more for Beto in the final stretch. “If he doesn’t win, I’ll continue doing this till the presidential election. I’m not stopping,” Hays told me.

In the final week, the Cruz campaign saw the Texas senator’s wide lead evaporating by about a point a day, according to Jeff Roe, his campaign manager.

That was in part due to presidential-level turnout in many places, fueled by the Beto campaign’s extensive volunteer network, which over the course of the entire race knocked on 2.8 million doors, sent more than 10 million texts and made about 20 million phone calls.

Still, such a massive volunteer operation presents its own challenges.

Self-guided volunteers — many knocking doors for the first time — aren’t always as efficient as a more controlled field operation. Many of the volunteers were white liberals who tended to live and blockwalk in more affluent suburbs and urban neighborhoods. The campaign eventually began marshaling paid organizers and volunteers to higher priority areas in low-turnout communities of color.

Cristina Tzintzun, who heads Latino organizing group Jolt Texas, acknowledges that O’Rourke ran a transformational campaign that did a million things right, but says there were inherent blind spots. “A volunteer program will not get you a huge base of black and brown volunteers because they don’t have the time and money to do that,” Tzintzun said. The campaign, she added, was slow to get into communities of color and found itself running against the October 9 voter registration deadline. “That was really unfortunate,” she said.

As GOTV ramped up, the field team released a real-time heat map showing precisely how many voters they still needed to reach in each precinct, color-coding them by priority level. That was unprecedented access to sensitive information, but the campaign thought it would help volunteers better direct their own efforts.

“I think a lot of people running for president in 2020 need to take lessons from [Beto’s field team].”

In the final stretch, the campaign would blast out messages to its email list updating supporting on their progress and imploring them to keep going. On the final Saturday before Election Day, the campaign knocked on 225,000 doors — more than the entire month of September. On November 4, its most prolific door-knock day, the campaign was hitting 340 doors a minute.

“I guess the best way to put it is if you look at every poll, he outperformed all of them. That’s at least partly field [work]. I think it was and is hugely vital,” Wysong said.

Democratic campaign veterans were impressed. Jeremy Bird, the Obama wunderkind who launched Battleground Texas ahead of the state’s last midterm election, bristled at direct comparisons between Wendy Davis’ 2014 gubernatorial bid and 2018, but was nonetheless complimentary of Beto’s campaign. “Their results speak for themselves,” he told the Observer. “I think a lot of people running for president in 2020 need to take lessons from [the field team].”

Claire Sandberg, who was in charge of Bernie’s 2016 distributed field program, thinks the Beto campaign should serve as a model for future campaigns. “What the Beto field team did was no small feat. Making a Senate race in Texas close in 2018 was the result not only of an inspiring candidate and a loathed opponent, but the product of millions of hours of volunteer effort,” Sandberg said.

But Roe, Cruz’s campaign manager, has a different interpretation. Beto got so close, he says, because he was a uniquely talented candidate who was able to raise a lot of money in a uniquely favorable political climate. “I think if anyone can replicate 80 million bucks with a two-year breathless campaign, with breathless coverage and completely positive press … then yeah, I think anybody could do it,” Roe told the Observer. “But it’s certainly hard to recreate some of that, [like] Ted as a motivator for base Democrats.”

A gleefully shrewd tactician, Roe clearly enjoys trolling his opponents, but he raises an important point.

O’Rourke’s message and authenticity inspired fierce loyalty and it’s why, even after losing, he’s the hottest commodity in presidential speculation. But it’s also exposed the challenges of building a movement around a single politician.

“It’s not healthy for democracy,” Congresswoman-elect Veronica Escobar, a close friend of O’Rourke’s who won her race to take over his El Paso congressional seat, told me. “This is not about one person, one candidate. This is about the entire country. Whether our candidates win or lose, we need every person to stay in the game.”

So can the energy that Beto summoned in Texas be replicated without him? It’s hard to imagine, say, Julián Castro, who sat out the 2018 cycle in Texas and now wants to run for president in 2020, being able to generate a similar grassroots movement — one that inspires volunteers to take leave from their jobs or donate their house for a month.

After the Bernie campaign, Bond began thinking about the central organizing principles that emerged from the chaotic flurry of trial-and-error. While Sanders certainly wasn’t the most charismatic politician, his big, bold message acted like smelling salts for the body politic.

She described them in a book she co-authored with fellow Bernie organizer Zack Exley, Rules for Revolutionaries: How Big Organizing Can Change Everything. As they determined with Rule No. 1: “You won’t get a revolution if you don’t ask for one.” As Bond wrote, “People are waiting for you to ask them to do something big.”