While prison officials insist they’re doing their best in the face of an unprecedented crisis, Governor Greg Abbott has mostly ignored the pandemic inside the Texas prison system.

Two months ago, as the threat of COVID-19 began to rapidly alter life on the outside, Sam says changes were happening more slowly inside the Wynne Unit, a state prison in Huntsville, where he’s currently incarcerated. Even as cities banned mass gatherings and told people to stay home, life in lockup remained mostly the same. That is, until late March, when the first Texas prisoners and prison employees began testing positive for the novel coronavirus. Sam remembers that officials banned activities like basketball at recreation at about the same time they started blocking visitors. Then came clumsy attempts at social distancing in a place designed to pack people together. At one point, corrections officers forced inmates to spread out in the chow hall tables even after cramming them all together in the line for food. “It’s kind of silly, but there’s really no way social distancing can be accomplished in this environment unless they removed half the inmates,” Sam wrote in a recent letter.

Sam, whose real name I’m not using to protect him from retaliation, was one of several incarcerated people who wrote to me in recent weeks suspecting they had COVID-19 but weren’t counted in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice’s (TDCJ) tally. Some say that’s because staff didn’t take their symptoms seriously early on, while others, like Sam, claim they hid symptoms to avoid medical isolation—a type of solitary confinement where prisoners claim they’re often denied basic amenities like cups or blankets. Sam says the majority of the 53 men in his dorm showed signs of infection but concealed it from prison staff, opting instead to wait out the potentially deadly virus on their own rather than risk a trip to solitary.

The Wynne Unit is one of more than a dozen prisons in Texas where inmates have been on lockdown for more than a month because someone inside, either a prisoner or an employee, recently tested positive for COVID-19. As of this week, 43,700 of the 140,000 people incarcerated by TDCJ are on lockdown. As the isolation continues, prisoners complain they’re going hungry after being forced to subsist on unpalatable sack meals for weeks while confined to their cells or dorms. Many of them are denied regular access to phones, making snail mail their only real connection to the outside. Even that lifeline has slowed to a crawl—some people with loved ones inside haven’t received letters for several weeks.

“When it comes to prisons, I don’t think Texas has been a leader during this pandemic at all.”

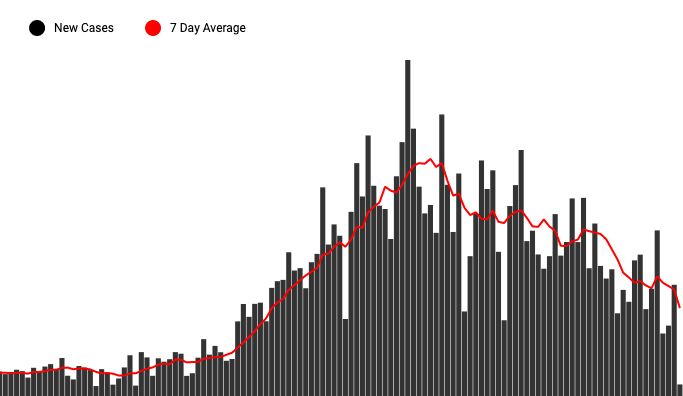

As of Wednesday, 1,775 prisoners and 677 TDCJ employees had tested positive for COVID-19, including 32 inmates at the Wynne Unit who currently have the virus. At least 30 prisoners and seven prison staffers with coronavirus have died over the past month, including several who worked or were incarcerated at the Wynne Unit. Civil rights lawyers and prisoners worry those numbers will continue to rise and have accused prison officials of failing to adopt adequate measures to stop the virus from spreading in the Texas prison system.

While prison officials insist they’re doing their best in the face of an unprecedented crisis, Governor Greg Abbott has largely ignored the pandemic inside the Texas prison system. Since March, prison reformers and advocates for incarcerated people have urged Abbott to take steps to lower the prison population, which experts say is the best way to reduce the risk for prisoners, prison staff, and the communities to which they’ll return. About 77,000 people incarcerated by TDCJ are eligible for parole. Another 15,000 people have been approved for release and are waiting for counseling, substance abuse classes, or other programs they’re required to finish before leaving lockup—programs that prisoners claim have been delayed during the pandemic. As I’ve written before, some of those people have serious health problems that make them more susceptible to the virus.

Over the past month, families of sick and elderly prisoners who are eligible for release have tried and failed to get Abbott’s attention. Some worry the kind of prisoner releases occurring in other states are off the table here, at least judging by the governor’s attempts to block local efforts to depopulate county jails. Advocates for incarcerated Texans say their pleas have mostly been ignored by Abbott’s office, which didn’t respond to my requests for comment. “It’s just, ‘Thanks, we’ll take it into consideration,’ and then silence,” said Doug Smith, a senior policy analyst with the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition. “Even as the situation’s getting worse, they just won’t talk about releasing people.”

Abbott has refused to consider prisoner releases despite the praise his state has received in recent years for reducing its carceral footprint. Over the past decade, Texas has fostered a national reputation as a leading prison reformer, largely because officials lowered the prison population in order to avoid spending billions constructing new lockups. As a result, eight prisons in Texas have closed in recent years, and two others were scheduled for mothballing this year, before the pandemic hit.

Despite that reputation for reform, Texas’ response to the spread of COVID-19 behind bars casts the state in a different light. “We’re seeing way more releases in so many other states, both red and blue states, where there’s a greater commitment to reducing the prison population as well as mass testing,” says Michele Deitch, an expert on prison conditions who teaches at the University of Texas at Austin. “When it comes to prisons, I don’t think Texas has been a leader during this pandemic at all.”

Several years ago, faced with an outbreak of a severe strain of influenza inside one of his prisons near Spokane, Washington, Eldon Vail knew he’d have to make exceptions to some of the normal rules. Vail, a former Washington prison official, said he doubled the amount of janitors inside the prison in order to constantly clean surfaces like doorknobs and dayroom tables, but he also gave prisoners access to alcohol-based hand sanitizer—which he acknowledged is usually considered contraband and carried a “moderate risk” behind bars.

“You might have a knucklehead somewhere that decides to drink it, but that pales in comparison to trying to get a handle on this flu epidemic,” Vail testified in a recent court hearing. He said he couldn’t remember a single prisoner who took advantage of the hand sanitizer by, say, drinking or starting fires with it. “The prisoners were pretty serious about trying to help us get through this,” he said. “They didn’t want to get sick either.”

Texas has taken a more cautious approach in the face of COVID-19. By late March, TDCJ’s response to the virus’s growing threat triggered a federal lawsuit by civil rights lawyers and two elderly inmates at the Pack Unit, a geriatric prison near Navasota, who claim the state’s plan to prevent coronavirus from spreading behind bars has been “grossly inadequate.” Despite guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommending that prisons and jails relax prohibitions on hand sanitizer wherever possible, Texas prison officials have refused to provide access to it. Assistant attorney general Christin Vasquez defended the agency in a court hearing last month, saying, TDCJ is “constrained by its security concerns.” She couldn’t provide a single instance of a prisoner ingesting or setting it on fire.

Laddy Valentine, 69, testified by phone that he lives in a dorm with 52 people at the Pack Unit, which he says makes social distancing impossible. In a federal court hearing in the lawsuit last month, Valentine said some prisoners know little about the virus or how to protect themselves from it because the only education from prison staff is some posters on the walls. Valentine spoke of one man in his dorm whom he helps write letters to his sister because he can’t read or write. “I’ve been writing so many that I know his name and number. He does manage to sign them, but it takes a while,” he said. “He just showed me his paperwork where he has a 67 IQ. He’s just illiterate.”

Despite guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommending that prisons and jails relax prohibitions on hand sanitizer wherever possible, Texas prison officials have refused to provide access to it.

Richard King, a 73-year-old janitor at the Pack Unit, testified that the prison didn’t have enough janitors or supplies to keep the prison clean. He said the paltry amount of disinfectant and powdered bleach he gets every morning barely lasts the first half of his 12-hour shift, and that he and the other janitors often have to share a single pair of gloves during a shift. “Whoever cleans the bathroom, that’s who uses the gloves,” he said.

In mid-April, federal district court Judge Keith Ellison issued a lengthy list of orders for staff to follow at the Pack Unit to better protect prisoners from the virus, including providing access to hand sanitizer and face masks for prisoners, along with extra toilet paper, cleaning supplies, and gloves and masks for inmates who work as janitors. Ellison wrote that TDCJ’s “lack of willingness to take extra measures, including measures as basic as providing hand sanitizer and extra toilet paper, to protect them [prisoners] reflects a deliberate indifference toward their vulnerability.”

Days before Ellison’s order, Leonard Clerkly, an inmate at the Pack Unit who tested positive for COVID-19, died after being sent to a local hospital for difficulty breathing. Ellison wrote that Clerkly’s death showed that TDCJ at the time wasn’t even following its own policies to prevent the spread of the coronavirus, despite an ongoing federal lawsuit over the matter. “Defendants made no representations to the Court that they identified Mr. Clerkly as symptomatic, evaluated him for potential COVID-19 infection, or isolated or treated him for COVID-19 at any point before his transport to the hospital on the day of his death,” Ellison wrote. “What is clear is that Pack Unit did not implement further precautionary measures until three days after Mr. Clerkly’s death, when his COVID-19 test came back positive. In the meantime, countless inmates were knowingly exposed to a serious substantial risk of harm.”

“They [TDCJ] simply have carte blanche to do whatever they want.”

State lawyers immediately appealed to the federal Fifth Circuit, which in late April blocked Ellison’s order, calling it an “administrative nightmare” for TDCJ. The appeals court has set the case for oral arguments on June 4; meanwhile, Judge Ellison’s order remains on hold. On Tuesday, the agency announced a plan for more widespread testing behind bars, which so far has shown a staggeringly high rate of infection compared with the state overall.

“Increasing the information available to our medical professionals will help us to further enhance the agency’s ability of stopping the spread of COVID-19,” Bryan Collier, TDCJ’s executive director, said in the statement.

Over the past month, Judge Ellison has repeatedly circled back to the question of whether the state can lower its prisoner population as a response to the pandemic—in particular, expediting the release of elderly and infirm people who are eligible to get out. So far, state lawyers have effectively shrugged and pointed to Governor Abbott and the parole board that he appoints, which has up to this point made no changes regarding releases during the pandemic.

In court, Ellison sounded befuddled by the state’s resistance. “I would expect the state would be pleased to be relieved from the responsibility for some inmates, would be happy to tender them back to their family units and let the onus of care and treatment be on the family rather than with the institution.”

COVID-19 has exacerbated crises that existed inside the Texas prison system well before the pandemic arrived. In the best of times, for instance, chronic understaffing put a strain on corrections officers who have to travel to fill in at another facility. During a pandemic, it’s meant that guards have had to bounce between prisons with and without coronavirus cases.

At the same time, the threat posed by COVID-19 in the Texas prison system has underscored the need for reforms that advocates for incarcerated people have been demanding for years. For several sessions, they have pushed bills in the Texas Legislature to create independent monitoring of the prison system. They say independent oversight, which is what lawmakers mandated for the state’s scandal-plagued juvenile system more than a decade ago, would shine a light on inhumane conditions inside prisons. Independent oversight could also give families an administrative avenue to turn to if prison officials dismiss complaints about loved ones wasting away in isolation or cooking to death inside uncooled prisons during the hot summer months.

Given TDCJ’s actions during the pandemic, such legislation could get a markedly different reception when lawmakers go back to the Legislature in January. Leaders in Fort Bend and Brazoria counties have clashed with prison officials over the past month, claiming prisoners with COVID-19 were transferred to lockups in their jurisdictions without prior notice (TDCJ says infected prisoners were transferred to be closer to the agency’s prison hospital in Galveston). With local officials now claiming that the agency’s lack of transparency has created a public health risk outside prison walls, some wonder whether there will be more support for independent monitoring of the system next session.

“I do hope that this next go-around, that these local communities understand and have firsthand experience having trouble with this agency,” said Representative Jarvis Johnson, a Houston Democrat who carried a bill for independent oversight last session and plans to do so again next year. “They [TDCJ] simply have carte blanche to do whatever they want.”

Johnson says he understands why people with incarcerated family members might feel hopeless trying to get information out of the prison system during the pandemic. While TDCJ has set up a hotline for concerned family members, as well as biweekly conference calls with inmate family groups, many people told me that they struggle to get accurate information about loved ones who are on lockdown because of coronavirus cases. Some have family members who have already been approved for release but are waiting to finish programming; while people inside claim classes and other programs are stalled, prison officials insist there have been no delays or changes.

Some families struggle to even figure out whether a loved one has coronavirus at prisons experiencing outbreaks. Gloria Salazar, whose son is incarcerated at the Wynne Unit, worried that he would contract the virus after he told her his job in prison required him to deliver food to inmates in quarantine, without a mask or gloves. The last call she received from him was over a month ago. One of his last letters was from early April, right before the prison went on lockdown.

Salazar says that for most of April she called the family hotline to see if her son was healthy. She says the call would often get bounced to other officials, who would tell her to call someone else, or who would then just hang up on her. “Usually there was nobody to answer my questions. They’d tell me to call back tomorrow or just hang up on me,” she said.

Last week, Salazar got a letter her son had written nearly two weeks earlier saying he’d tested positive for COVID-19. He told her he was having difficulty breathing and couldn’t smell or taste anything. She hopes his next letter contains better news.