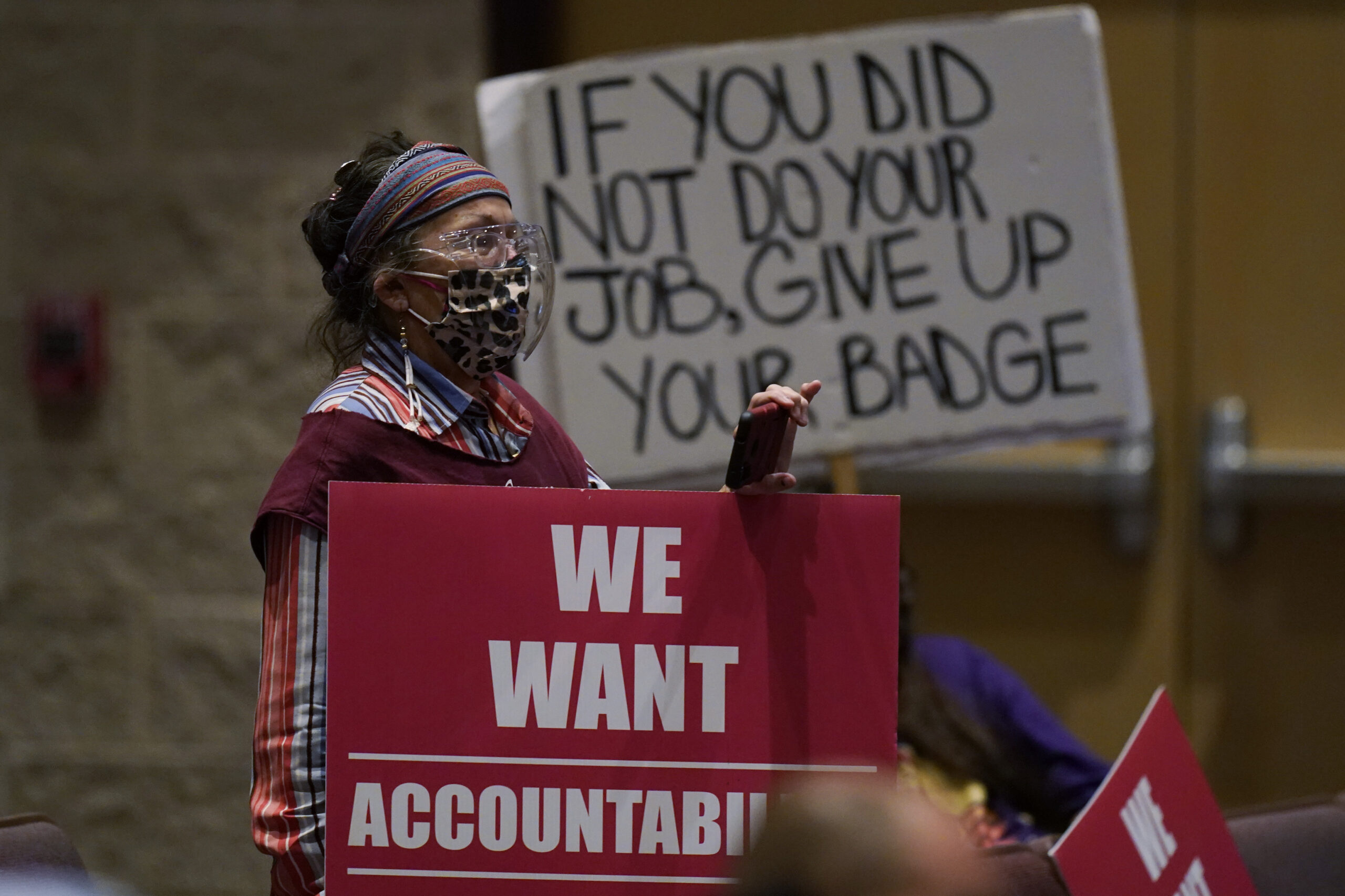

How Public Corruption Investigations Can Fail

A former Texas Ranger provides rare insights into the mostly secret system set up to investigate complaints about public officials.

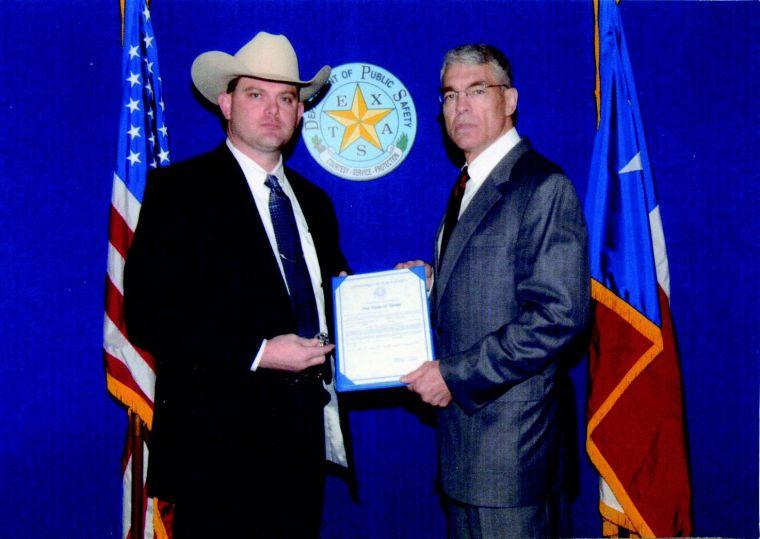

Chris Callaway served as a Texas Ranger from 2012 to 2018 and worked on public integrity cases, including investigating both local officials and a legislator. Statewide, Rangers like him handled more than 560 cases involving corruption by local and state officials from 2015 to 2020. But few ended in prosecutions, a Texas Observer investigation found. Over the years, Callaway spotted problems in how some cases were handled. “I did the best I could, but a lot of obstacles were in the way,” he says. Callaway left DPS in 2020.

Texas Observer: In the last five years, more than 500 public corruption cases have been investigated by the Rangers all across Texas. How many Rangers and supervisors outside of the Rangers’ public integrity unit in Austin have expertise in these kinds of cases?

Callaway: Most don’t. The Rangers are a small group and the public integrity working group was even smaller. There’s three or four in Austin who do it full-time. The rest do it on an as-needed basis.

Why is a Ranger supervisor and often a district attorney asked to approve a public integrity or public corruption investigation before a Ranger can open one?

That policy was put into place by the Rangers division so we don’t find ourselves involved in taking out political adversaries. We’re not going to investigate an allegation of voter fraud in the middle of an election. They try on the investigative side to be objective. They’re ultimately concerned with their image—above all else. That’s the reason the [supervisors] started to vet some of those complaints.

Did you think sometimes that vetting process went too far? Did the screening by Rangers or DAs get in the way of legitimate complaints?

Yes. I remember one case involving an official in a little bitty podunk town. We knew a guy was stealing money and drugs. He was depositing stolen money in his personal bank account, but I couldn’t investigate that guy because he was an elected official. I had to go through a bureaucratic process. The answer I got was no. So the bureaucratic process sometimes prevented investigations in cases involving public officials.

What’s the role of a DA in screening public integrity investigations?

Once we got the blessing from the chain of command, then often we had to get a letter from a DA saying that if the investigation produced evidence of a prosecutable criminal act, he or she would proceed. The way the rangers look at it, if the DA doesn’t want to prosecute, we’re not going to waste our time investigating.

Isn’t that process backward? How do you know you’ll find a prosecutable offense if you can’t investigate?

That’s the part of the thing I struggled with. Because when we start looking at [a complaint] we don’t know what else we’re going to find.

In the last five years, public integrity complaints made against legislators and statewide office holders all seem to have died quietly—with the exception of the long-running prosecution of Attorney General Ken Paxton in Collin County. Did you think more public integrity reports should be released?

Yes. In high-profile cases, I think that all cases that are closed—even if no prosecution was ever done—the reports should be made public. You should be able to look at them. One prosecution [against Paxton] is ongoing, so that report should be withheld. But there have been other complaints made against him that were investigated, and those reports should be released.

I did an investigation into a legislator involving a business transaction that occurred between him and a family friend.It involved air conditioners and a hunting trip. I can tell you that what he did may have been unprofessional or even immoral. But it wasn’t illegal. I came to believe that the complaint against him had been motivated by political disagreements over border security initiatives. I think that report should be released.

In some public integrity cases, DAs have said Texas ethics laws are too weak. For example, a Kaufman County prosecutor declined to proceed on a Ranger’s investigation of how Paxton accepted $100,000 from a businessman whose company was simultaneously being investigated by the AG for Medicaid fraud. Texas law against giving an illegal gift to a public official is only a misdemeanor and she said that law has loopholes.

Look at the state statues—the statutes for the majority of those kinds of offenses are misdemeanors. So, you’ve got a bunch of attorneys writing laws in Austin and attaching punishments to them, so that in the event one of them violates the law, it’s a misdemeanor and it doesn’t keep him or her from practicing law… you just don’t get much results.

For example, you can violate the civil rights of a person in custody; that’s a Class A misdemeanor, as are other official oppression crimes. But if you falsify your school attendance records, that’s a third degree felony. What’s wrong with that picture?

If nothing changes in Kaufman County, that gift case will never be prosecuted and you’ll never even get to see the Ranger’s report.

Rangers are supposed to be investigating public integrity, public corruption, in-custody deaths, serial killers, cold cases, and conducting border security. Is it possible for the Rangers to carry out all of their missions with the number of officers they have?

It is completely impossible to carry those duties out effectively. One of my biggest regrets of my Ranger career is that my frustration and aggravation led to an alcohol addiction problem. That’s what started my descent into unemployment. The expectations placed on those guys and gals is just outrageous. It’s completely unsustainable for an extended period of time. How can you be a top-notch public integrity investigator or a top-notch murder investigator if you’re not allowed sufficient time to develop those skills?

Can you talk more about why you left DPS in 2020?

In law enforcement, there’s rampant alcohol and drug abuse, PTSD. It’s more widespread than anybody talks about. They don’t want those kinds of stories to be told. I went three times asking for help. I finally ended up in a treatment program specifically for first responders and veterans. It’s called the Warrior’s Heart. I talked about that publicly. After that, I got fired. I have a lawsuit in Hidalgo County court—a 2019 civil rights case that alleges that DPS discriminated against me because I admitted to a disability.

Can you get a copy of the report on the public integrity/internal affairs complaint that you made about your supervisor?

No. It’s not public. I made a public information act request and I was told by the AG that it’s not public because no disciplinary action was taken by DPS.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.