How Tea Partiers Fueled Texas’ Latest ‘Voter Fraud’ Freakout

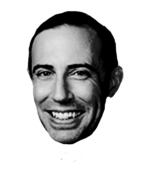

Election-related crimes are rare, but activists like Aaron Harris have become both a legal and political weapon in Texas Republicans’ war on election fraud.

A version of this story ran in the March / April 2019 issue.

In August, a group of outraged conservative activists sent Governor Greg Abbott a letter that helped spark Texas’ latest voter-fraud scare.

Signed by more than 100 tea party leaders across the state, the letter declared, “The fact that our Texas elections are being compromised is beyond question.” In a press conference announcing their demands, JoAnn Fleming, an East Texas tea partier who’s been beating the immigrants-are-invading drum for years, warned that hundreds of thousands of “illegals” had registered to vote in the state.

“Reasonable people understand that American citizens get a little hot under the collar if they believe their votes can be stolen by someone here illegally,” Fleming said before passing the mic to Aaron Harris, a Tarrant County political operative affiliated with the Empower Texans wing of the state GOP. Harris, who Fleming called the “subject matter expert” on all things voter fraud, reserved most of his venom for Texas’ top elections official, Secretary of State Rolando Pablos, an Abbott appointee, who he claimed had failed to adequately police the state’s voter rolls.

“We’re asking [Abbott] to step in and ask the secretary of state to check the citizenship of people who register to vote in Texas,” Harris said. He later provided a citizen-action toolkit for conservatives to push for action before the November midterm election — talking points, sample posts for social media and scripts for flooding the governor’s office with calls and emails. “What we know is that Governor Abbott has historically been very responsive to public pressure, he’s been very responsive to the grassroots,” he told conservative organizers on a conference call later that week.

Harris didn’t get his wish until after the midterms. On December 17, shortly after Pablos resigned his post, Abbott made David Whitley, one of his longtime right-hand men, Texas’ new secretary of state. After just five weeks on the job, Whitley made an explosive announcement: His office had flagged 95,000 “possible non-U.S. citizens registered to vote,” 58,000 of whom had already voted at least once. At the same time, Whitley instructed county elections administrators on how to scrub the names from the voter rolls; elections officials in more than a dozen counties then immediately sent notices threatening to revoke registrations for people who failed to respond with proof of citizenship within 30 days. On Twitter, Attorney General Ken Paxton issued his own “VOTER FRAUD ALERT.” Abbott thanked his former deputy for uncovering “illegal vote registration” and called for prosecution, and Donald Trump eventually twisted it all to claim that 58,000 non-citizens had voted in Texas.

The allegations began to collapse almost as soon as they were made. Less than a week after issuing his advisory, Whitley told county election officials that his office had already determined that tens of thousands of naturalized citizens had been mistakenly included on the list. Civil rights groups have since filed three lawsuits alleging the botched purge discriminated against naturalized citizens and was designed to scare people out of registering or voting.

Harris, the voter fraud “expert,” isn’t chastened in the least by the fallout. “Watching Democrats justify crime is delicious,” he said on Twitter.

Harris is emblematic of how the right-wing fixation on voter fraud in Texas has shifted in recent years. As Paxton fought in court to uphold one of the strictest voter ID laws in the country, Harris helped seed the field for more alarming headlines to fuel the attorney general’s crusade.

Harris has become both a legal and political weapon in Paxton’s war on election fraud. While election-related crimes are exceedingly rare, Harris has spent years attempting to root out its most common iteration: the manipulation of mail-in ballots. In Tarrant County, he claims to have personally uncovered “vote harvesting” operations that crossed the line and engaged in fraud — such as forging people’s signatures on mail-in ballot applications to boost absentee voting in certain neighborhoods. Harris’ allegations triggered legislation cracking down on the practice, which isn’t necessarily illegal, and increasing criminal penalties during the 2017 legislative session. He even fed the allegations to Paxton, whose office turned them into big, screaming election fraud indictments on the eve of the 2018 midterms.

Voting rights experts have warned about conservatives using isolated scandals, especially involving mail-in ballots, to fuel a larger, misleading narrative about election security that places the burden on voters — like requiring photo ID at the polls or proof of citizenship to register. For instance, lawmakers in North Carolina, reeling from the biggest absentee ballot fraud scandal in recent memory (implicating a conservative Republican, not an immigrant), passed new rules requiring voter ID for mail-in voting, a new restriction that wouldn’t have prevented the state’s current debacle.

“We are changing the entire discussion on voter fraud in Texas.”

Last year, amid baseless, Trump-fueled hysteria about immigrants rigging elections, Harris and other Texas conservatives turned to the spectre of non-citizens voting in Texas, a kind of election fraud that experts call vanishingly rare. Harris’ group, Direct Action, continues to argue that routine maintenance of county voter rolls already conducted by elections officials isn’t enough.

Civil rights groups tie the bungled purge to Texas’ long history of discrimination against minority voters. In an interview, Harris scoffed at the fear that wide-scale purges could suppress voting. “When Democrats don’t get their way, they cry racist,” he told me. “If we do anything for election integrity, they yell voter suppression.”

Last month, after hearing days worth of testimony on the rollout of Whitley’s recent effort to scrub the rolls, San Antonio federal district court Judge Fred Biery called the operation a ham-fisted solution in search of a problem. “[T]here is no widespread voter fraud,” Biery wrote in an order last week that ground the purge to a halt. “The challenge is how to ferret the infinitesimal needles out of the haystack of 15 million Texas voters.”

Whitley’s flawed advisory to county elections officials was apparently just the beginning. In court last month, state officials said they plan to send monthly lists of registered voters to counties for citizenship checks.

It’s a broader effort to police the vote that Harris is proud to have fueled. “Sometimes you have to force the conversation,” he said. “We are changing the entire discussion on voter fraud in Texas.”

–

Before Aaron Harris became the Texas GOP’s go-to guy for voter fraud, he mostly ran with a crew of anti-tax conservatives railing against wasteful spending in the Metroplex.

In 2014, Harris joined Monty Bennett, a multi-millionaire hotelier and tea party moneyman from Dallas, to create a for-profit political consulting firm called Grassroots Groundgame, LLC, according to business filings with the secretary of state’s office. The firm appears to have mostly focused on campaigning against local bond elections, with Harris operating under the offshoot Direct Action Texas. In 2015, Harris and Bennett backed challengers attempting to shake up the Tarrant Regional Water District after Bennett discovered the board had approved plans to build a pipeline through his ranch.

When his candidates lost, Harris claimed the election had been “stolen,” alleging that thousands of signatures on mail-in ballot applications didn’t match those on the envelopes for the actual ballots. The allegations centered on what Harris characterized as the shady “vote harvesting” tactic of seeding neighborhoods with mail-in ballots that people hadn’t ordered by forging signatures or otherwise improperly filling out applications for absentee voting. He zeroed in on two close 2015 races that he alleges were tainted by mail-in ballot fraud: Fort Worth City Council Member Sal Espino’s 26-vote victory and state Representative Lon Burnam’s 110-vote loss in that year’s Democratic primary.

“It’s just gross, gross, gross conflating.”

In an attempt to prove the theory, Harris orchestrated a sting of sorts: He deployed canvassers to minority neighborhoods in the county’s north side precincts, pretending they worked for a get-out-the-vote PAC conducting post-election research on people’s experience with mail-in voting. Once canvassers got the voters talking, they fished for information on whether anyone had helped them vote by mail.

In October 2016, less than a month before the presidential election, Harris outlined the results of his probe into Tarrant County elections in a dramatic two-hour presentation at a packed Fort Worth tea party meeting. He accused local Democratic operatives of paying campaign workers to forge signatures on mail-in ballot applications, increasing the odds that key Democratic-leaning voters would vote by mail. He ran through slides of different mail-in ballot applications that appeared to show similar handwriting, claiming he’d discovered thousands of “fraudulent ballots.” He assured the crowd that this was “only the tip of the iceberg.”

In the room that night were Republican lawmakers, including state representatives Craig Goldman and Stephanie Klick, who would go on to help pass legislation in the 2017 session that expanded the definition of mail-in fraud and boosted criminal penalties, making it a state jail felony rather than a misdemeanor. Harris promised conservatives that increased penalties would make the crime a more attractive target for prosecutors — leading to more cases and thus more evidence of election fraud. Civil rights groups warned elements of the law could make mail-in voting more burdensome.

Harris called his work in Tarrant County “by far the largest election fraud case that Texas has ever seen,” so big that he turned his findings over to the Texas attorney general for prosecution. Harris wouldn’t give me a copy of the complaint he filed with Paxton’s office, which also refused to release it to a civil rights group attempting to vet Harris’ claims. Publicly, Paxton was mum on Harris’ work, though the attorney general retweeted Abbott’s posting of an Empower Texans story about the Tarrant County probe that said, “We will crush illegal voting.”

Two years later, in October 2018, less than a month before the midterms, Paxton announced the results. Though Harris had claimed Tarrant County elections were marred by thousands of illegal votes, just four Hispanic women were accused of forging signatures or “providing false information” on mail-in ballot applications for 28 people. One defendant was charged with a single second-degree felony count of illegal voting, accused of marking one elderly man’s ballot without his permission. If convicted, she faces up to 20 years in prison.

Harris clearly wanted the investigation to nab bigger fish: Court records show he accompanied a local Republican lawyer named Alex Kim to visit one of the defendants in jail the day after she was arrested. (Kim was elected to a district court bench the following month). Harris told me he wanted the defendant to flip on the people who paid her, mentioning Stuart Clegg, a former Tarrant County Democratic Party leader named, but not charged, in one of Paxton’s court filings in the case. (Clegg has denied he did anything improper.)

After the arrests, Greg Westfall, one of the attorneys representing the defendants, said the women were “political footballs being kicked back and forth by people who have a vested interest in suppressing the minority vote.” The judge on the case has since issued a gag order that prevents the parties from speaking publicly about the case.

“What we know is that Governor Abbott has historically been very responsive to public pressure, he’s been very responsive to the grassroots.”

Matt Angle is director of the Lone Star Project, a Democratic research group and political action committee that pushed back against charges of alleged mail-in fraud spearheaded by Abbott when he was attorney general. He argues Paxton’s election-fraud crackdown seems even more brazen because his office appears to be taking marching orders directly from Republican operatives.

“The entire point of Ken Paxton’s voter fraud efforts, which is an extension of what Greg Abbott did, is to pluck needles out of the haystack and make them look like giant swords and daggers to create this sense of fear and danger around voting,” Angle said.

Voting rights experts worry that even using the blanket term “vote harvesting” can demonize legitimate get-out-the-vote efforts aimed at mobilizing mail-in voters. Myrna Pérez, director of the voting rights and elections project at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University Law School, said conservative groups often use such cases to justify completely unrelated voting restrictions under the guise of widespread voter fraud — much the way lawyers for the state read stories about the Rio Grande Valley’s politiquera scandals into the court record while fighting to uphold Texas’ strict voter ID law.

“It’s just gross, gross, gross conflating,” Pérez said. “When it comes to election integrity, placing the burden and barriers on the correct people is important.”

Even some who agree with Harris’ work in Tarrant County question how he and other conservatives have since used it to rationalize a larger war on “illegal voting.” Burnam earlier this month urged the Texas Senate Confirmations Committee to reject Whitley because his misguided attempt to police the voter rolls.

East Texas Senator Bob Hall, a conservative defender of white nationalists who sits on the committee, was incensed that Burnam called illegal voting “practically non-existent.”

“Do you really believe that, or was that a misstatement?” Hall groused. Burnam shot back, “It’s virtually non-existent and the issue that keeps being exploited is the one that’s really intended to do voter suppression.” Burnam tried to explain the difference between “vote harvesting” and “illegal voting” before Hall cut him off.

–

Local elections officials say Whitley’s purge has put them in a difficult position. This latest effort to police the vote has pit their duty to maintain accurate voter rolls against their responsibility to protect voters’ rights.

“I don’t want to be the voter registrar who attends naturalization ceremonies and who congratulates people who are becoming citizens, then asks them to register to vote and then months later turns around and say, ‘OK now show me your papers,’” said Remi Garza, Cameron County’s chief elections official. Garza pointed to people living in border regions born to midwives who now have trouble obtaining passports. “Am I going to get that list of people born to a midwife, saying they might not be citizens? I just don’t know where this might end. Will somebody eventually send me a list that has my name on it?”

Harris, of course, views the events of the past month in a different light. He calls it the necessary growing pains for a system designed to root out voter fraud. Naturalized citizens caught in Whitley’s purge were just the eggs you’ve gotta crack to make the omelette.

Harris left Direct Action Texas in December to become chief of staff for freshman Congressman Lance Gooden, but he remains on the board of the organization he founded. Direct Action, which Harris branched off as its own nonprofit in 2017, continues to both applauded Whitley’s advisory to county elections officials and chastise Abbott for failing to utter the words “voter fraud” during his state of the state address.

In our conversation, Harris repeatedly argued that Democrats not only turn a blind eye to voter fraud but actually want non-citizens to vote, pointing to a small number of cities on the coasts that have allowed it in certain local elections. “You think all this outrage is real?” he told me. “You think Democrats in Texas aren’t aligned with Democrats on the East Coast or West Coast?”

Last month Harris sent me an email asking for proof that Democrats don’t want non-citizens voting. I raised the issue with Luis Vera, an attorney for LULAC who’s suing the state over the purge, as he walked out of court a few days later. “That’s bullshit,” Vera told me. “We all know what this is about.”