Even Hurricane Harvey Can’t Temper GOP Hostility Toward Texas’ Big Cities

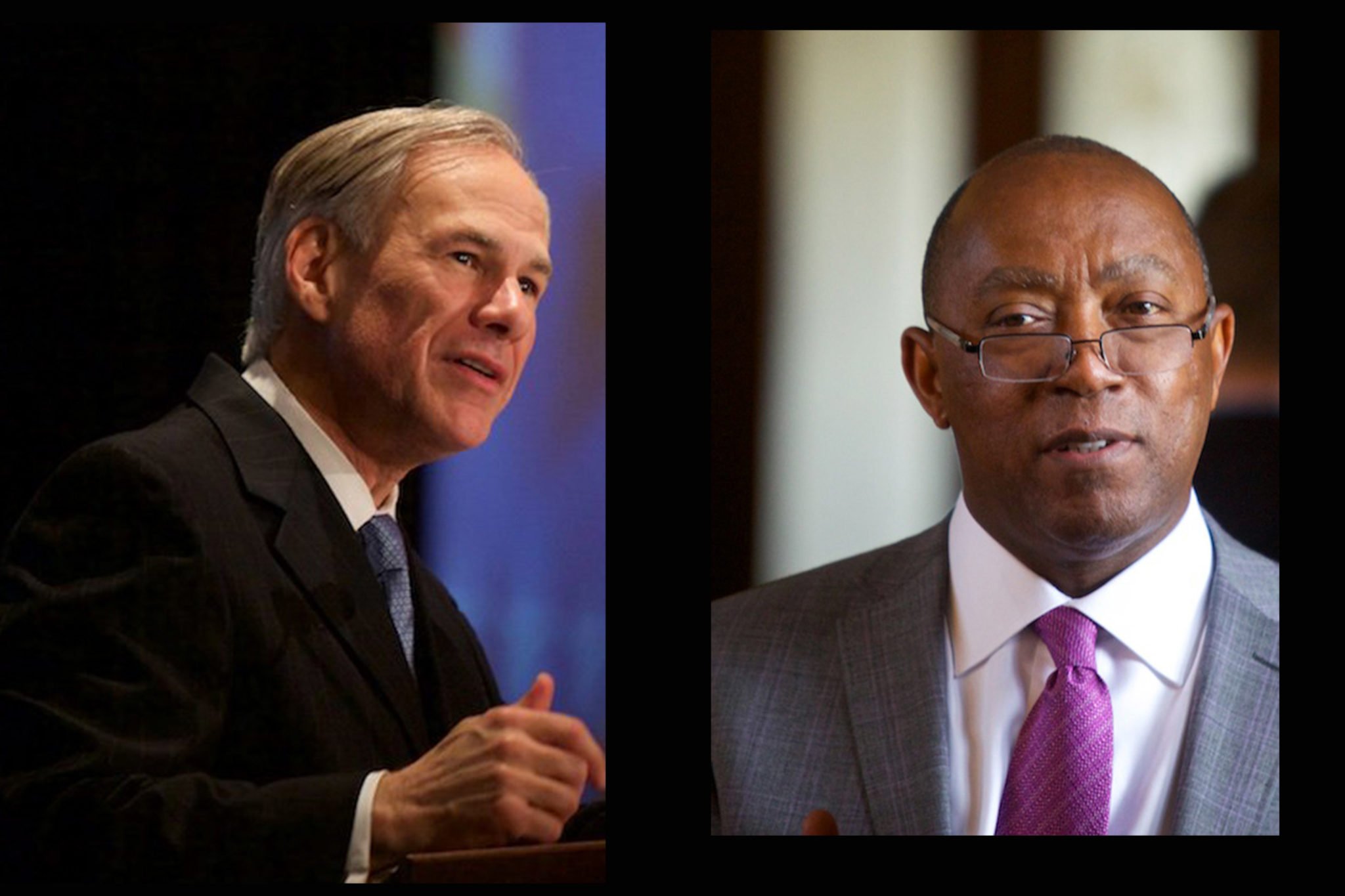

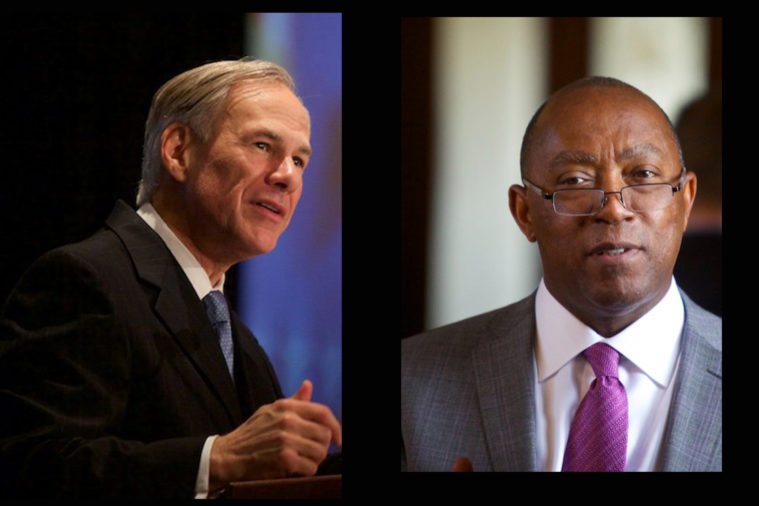

Governor Greg Abbott scoffed at Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner’s request for emergency funds, saying he "has all the money that he needs."

On August 4, less than a month before Hurricane Harvey made landfall, Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick appeared on the Fox Business Network with a diagnosis for what ails the nation. “Where do we have all our problems in America?” he asked. “Not at the state level run by Republicans, but in our cities that are mostly controlled by Democrat mayors and Democrat city council men and women. That’s where you see liberal policies. That’s where you see high taxes. That’s where you see street crime.”

In September, another big problem appeared over Houston, a messy city run by one of those dangerous Democratic mayors, Sylvester Turner. Houston is the state’s beating heart, and Harvey could end up being the most expensive natural disaster in American history. In the past, it would have been of some comfort to the mayor of Houston that the lieutenant governor and some of his top allies, such as state Senator Paul Bettencourt, hailed from the Houston area, because they’d help make sure the city’s needs were met in the months and years ahead. That’s not the case now, and it’s worth taking a moment to place Harvey in the context of the extraordinary animus the Legislature often seems to have for local governments and the people who run them.

Turner now has one of the most difficult and unpleasant jobs of any public official in the United States. To take just one example: An immediate crisis the city faces is waste removal — there are whole neighborhoods full of tall piles of ruined furniture and trash that will rot in the rain and attract pests. Turner recently told the city council that many of the contractors who do the kind of removal work Houston needs fled to Florida, for better rates after Hurricane Irma. The best case scenario is that “most” of the waste will be cleared by Thanksgiving, two months from now.

If things go slowly, residents will inevitably blame Turner, just as a backlash immediately materialized when he recently proposed a temporary 8.9 percent property tax hike, which would raise about $113 million for Harvey recovery. For the average homeowner in the city, that comes out to about $117 a year, which doesn’t seem like terribly much given the circumstances. More importantly, Turner’s hands were tied. The storm wiped out the city’s emergency funds and destroyed a lot of city property, and though FEMA will pay 90 percent of trash removal costs, Houston’s share is still something like $25 million. Nonetheless, Turner caught a lot of heat for the proposal.

Senator Bettencourt even told a Houston radio station that he’s against using any state money to help the city.

Later, a new agreement with FEMA caused Turner to reduce the amount he was asking for to $50 to $60 million. For the state, that’s chump change — the rainy day fund alone has more than $10 billion. Though state leaders have signalled a willingness to spend some of the rainy day fund on disaster relief, no one’s rushing to appear overly generous. When Turner’s hand was forced and the tax bump was proposed, state officials had two options: Reassure Houstonians about the forthcoming availability of state money, or let Turner, the Democratic mayor of a city Republicans are increasingly struggling to contest, twist in the wind.

You know which one they chose. “I don’t understand this mindset,” Bettencourt, Patrick’s lieutenant on tax issues and a resident of the city of Houston, told the Houston Chronicle. “It’s beyond tone deaf. I don’t believe governments should be showing this type of attitude when people are down. Taxpayers are going to be furious.” Bettencourt then added that he now opposes provisions that let local governments raise taxes more easily in the event of a disaster or emergency. Bettencourt told a Houston radio station that Houston should be “using the funds that are already there” before asking the state for money.

On Tuesday, after Turner made a public request for money from the rainy day fund, Governor Greg Abbott joined in, telling reporters that the fund wouldn’t be touched until the 2019 legislative session. Turner “has all the money that he needs,” Abbott said. “In times like these, it’s important to have fiscal responsibility as opposed to financial panic.” The governor went on to accuse the mayor of using Harvey recovery efforts as a “hostage to raise taxes.”

Bettencourt and Abbott are doing what state lawmakers frequently do now — putting political pressure on local governments to draw attention away from what the state is doing and gather ammo for future internecine battles in Austin. (All last session, Bettencourt was at war with local officials over property tax policy.) The difference now is that he’s doing it right after Texas’ largest city had its legs shot out from under it, at a time when you might hope Houston-area lawmakers would not only refrain from taking potshots at Turner, but find ways to affirmatively help him. But, hey, it’s just business as usual: Everything good in Texas is to the credit of the brave boys and girls of the Lege, and everything bad is the fault of county commissioners courts, city councils and school boards.

Aren’t the different layers of government supposed to work together? In Texas, they generally do not. I’ve talked to many local officials, including Republicans in deep-red counties, who can’t for the life of them get a call returned from their GOP state representative or senator. Even big-city mayors sometimes get the stiff arm, and lawmakers seem to take pleasure in nullifying or canceling popular city ordinances, sometimes because of lobby money but sometimes, it seems, simply out of spite.

Consider Houston before the storm. Its school systems are heavily penalized by the state’s school finance system, which forces locals to raise property taxes. It has huge immigrant populations whose relationships with the police were negatively affected by Senate Bill 4. The culture wars at the Legislature — and the poor quality of state services — hinder Houston’s appeal to the international business community. Houston’s health care system has suffered greatly from the Legislature’s refusal to expand Medicaid.

This is despite the obvious fact that Texas’ appeal, and strength, is the quality and dynamism of its big cities. Six of the nation’s 20 largest cities are in Texas, and each has a distinct identity and appeal. (Well, maybe not Dallas.) The state should be helping cities. To take but one too-late example, the Legislature is the only body that could have cut through the mess of overlapping political jurisdictions to control development and strengthen flood planning in greater Houston in a unified way.

Instead, we have a state government that sees its largest generators of economic activity — the six metropolitan areas in which more than half of the state lives — as some kind of threat, either because of their values or the demographic and political threat they represent to the Republican Party. You might hope Harvey would temper that, but don’t hold your breath.

Correction: The original version of this story stated that Bettencourt told a radio station that he opposed any funding for Hurricane Harvey recovery in Houston. In fact, Bettencourt said that Houston should exhaust local funding options before asking the state for money. The story has been corrected.