In 2017, Texas Union Membership Rose at the Highest Rate in Over Three Decades

“There’s more of a culture of organizing than ever before, and I’ve been in this job about 24 years," said one union staffer.

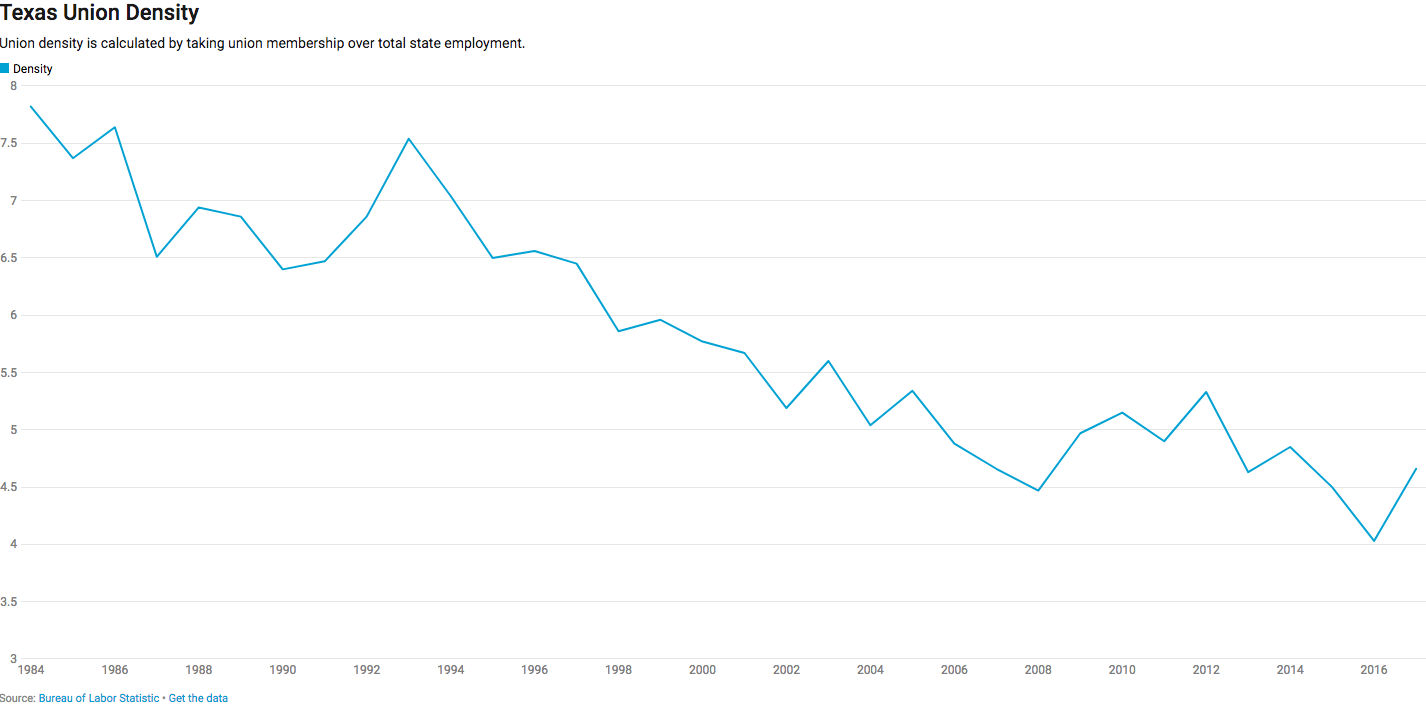

Even as union membership flatlined nationally in 2017, something surprising happened in the Lone Star State. Texas had its biggest surge in union membership since 1983, the first year that the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) began collecting state union data.

According to the BLS, Texas union membership grew by 80,579 people in 2017. Union density, the ratio of union members to the total workforce, grew modestly from 4 percent to 4.7 percent – the biggest jump since 1993.

The union boomlet corresponds with economic growth and shifting political affiliations in Texas cities. In progressive cities such as El Paso, elected officials have helped public-sector labor organizers put down roots. And in some conservative, rural parts of the state, private-sector unions have been able to attract members with apprenticeship programs that guarantee higher wages.

Other red states are also seeing measurable union growth. Over the last year, union membership density grew in other southern right-to-work states such as Virginia, Arkansas, Georgia and Louisiana.

“You can go to almost any state and find substantial organizing activity,” said Ed Sills, communications director of the Texas AFL-CIO. “There’s more of a culture of organizing than ever before, and I’ve been in this job about 24 years.”

Another surprise: Nearly two-thirds of Texas’ union growth was in the private sector, fueled in part by the state’s robust housing sector. Construction made up about 18 percent of the total growth in membership in Texas.

Paul Puente, executive secretary of the Houston Gulf Coast Building and Construction Trades Council, expects construction unions to keep growing, in part due to the Hurricane Harvey recovery effort. “We’re scouring the community for individuals who were directly affected by Harvey and we provide them with training and education at no cost to them,” said Puente.

“There’s more of a culture of organizing than ever before, and I’ve been in this job about 24 years.”

His trade council uses advertising to reach a broad network of Texans along the Gulf Coast looking for higher-wage jobs. Its apprenticeship readiness program provides a weekly stipend of $250 and training in technical skills such as plumbing, electrical work and ironwork.

Puente also attributes the growth in membership over the past year to the changing perception of construction unions as business-friendly. “We have a no-strike agreement,” he said. “We pride ourselves to be able to be as flexible as we can to our customers’ and our clients’ needs. That messaging has helped us gained market share.”

Puente sees marketing strategies, such as the TV and radio ads the council buys on University of Houston sports broadcasts, as softening the image of labor unions in the eyes of the business community. Ed Sills echoed this sentiment. “A lot of people are under the misimpression that labor doesn’t want corporations to do well,” he said. “We do, when we get a share of it.”

In the public sector, it’s another story. Rob D’Amico, communications director for Texas American Federation of Teachers (AFT), credits his union’s small but steady membership gains to grassroots organizing with a focus on political strategies.

“The best issues to organize around are always local issues,” said D’Amico.

For example, the El Paso chapter of the AFT attracted new members by focusing on what D’Amico calls “nuts-and-bolts issues” — personal leave, class sizes and unpopular principals.

Because Texas bans collective bargaining, AFT uses elective consultation, an alternative method of bargaining in which the union works to elect school board members who facilitate budget negotiations in its interest. This approach necessitates the union’s aggressive involvement in local politics.

“The labor movement is in a place where solidarity is really critical. When other unions win, we win.”

UNITE HERE Local 23, a national union representing food service, airport and hotel industries, embraced a progressive political platform as a part of its Texas campaigns. The union, which has offices in Austin, Dallas, Houston and San Antonio, recruited workers at the Marriott Marquis Houston, a 1,000-room hotel, in the past year.

William Gonzalez, president of the Texas chapter, says that the union’s membership in the state is concentrated in Houston, where 3,000 people have joined. He expects the Houston branch to grow by more than 1,000 in the next year. Gonzalez sees part of the spike as a reaction to the perceived anti-immigration sentiments of President Trump and Governor Greg Abbott. He thinks that politics is integral to the state’s union growth.

“What we try to get our membership to see is that the union rights are civil rights and civil rights are union rights,” said Gonzalez. But he added that the alliance of unions across political and industry lines is important for the future of the labor movement.

Solidarity across industries is especially important in states like Texas, where public-sector unions have faced an uphill battle for decades. It’s notable that the last surge in Texas union density was 1993, the year before right-to-work laws began to take effect, forcing membership into a two-decade decline. While the gains over the last year are significant, they’re minor in comparison with the overall losses that the state has incurred since then. From 1983 to 2016, union membership declined from 9.7 to 4 percent of the Texas workforce.

“The labor movement is in a place where solidarity is really critical. I think it’s important to demonstrate that we can win,” Gonzalez said. “When other unions win, we win.”