In a System that Encourages Corruption, Prison-Bound Senator Carlos Uresti was Inevitable

The state’s part-time Legislature and weak ethics laws allow corruption to flourish. Uresti was just stupid and brazen enough to get caught.

It’s one thing to be useless and honest, and another thing to be useful and crooked, but it’s another thing entirely to be useless and crooked. Useless and crooked: That’s how former state Senator Carlos Uresti ends his more than two decades in public service. On Tuesday, he was sentenced to 12 years in prison for his entanglement in a messy web of fraud and bribery. In the final analysis, Uresti was an inessential lawmaker guilty of crimes that would disqualify anyone from public life forever. He won’t be missed.

Uresti’s legal difficulties are complicated, extensive and salacious. Amid faltering personal finances in recent years, he started bilking his legal clients and trading on his elected office to make money in a way that became so audacious it eventually attracted the feds. Somehow he also found time to become infamous around Austin, allegedly, for serial sexual harassment.

I won’t ask you to sympathize with Uresti, because he doesn’t deserve it — he put on a suicide vest and blew it up, hurting a lot of other people in the process. But I will try to offer a way of understanding Uresti, in the manner of one of those third-rate crime movies in which it turns out the real criminal was Society all along. Here goes: The state of Texas has built a political system that is effectively designed to produce petty grifters, which it succeeds in doing with great regularity. Uresti is an aberration only in the sense that he went too far and got caught, and that he attracted the attention of a powerful and well-resourced out-of-state law enforcement organization. That’s his stupidity, but our sickness.

Have you heard that the Texas Legislature is “part-time?” It’s a point of pride for some people, particularly Republicans, that the Legislature only regularly meets for five months every other year, working overtime to develop plans and funding for state agencies two years into the unknown future. It’s a point of pride, too, that lawmakers are expected to have a “real” job to sustain them while they’re making laws. Legislators are only paid $600 a month, plus a per diem when the Legislature is in session. That averages out to about $20,500 a year — more if special sessions are called, but not much more.

If that sounds like a weird and suboptimal way to govern what would be the world’s 10th-largest economy, that’s because it is. It’s a relic first outlined in the 1876 constitution, at a time when the state was an underpopulated, unimportant backwater. Most states had biennial legislatures then. Back then, it made sense, and especially so for Texas — state government didn’t have all that much to do, and it was very hard to get around the state. So all the farmers and ranchers who got elected in their rural districts would come to Austin for a few months, make laws, and then go home.

But as the state got richer and richer, more money seeped into the political system. By the beginning of the last century, as depicted in Robert Caro’s The Path to Power, the farmers and ranchers would come in from their small towns, and the lobby would be there — utilities, railroads, oil. They paid lawmakers’ room and board in town, or they paid their tabs at the brothels and bars that lined Austin’s Congress Avenue. Then as now, the lobby lives in the capital, but the lawmakers are only visiting. They’re often unsophisticated, and cash-poor, and they make easy prey.

Over time the bribery gets more discreet, and the brothels go away, but the core dynamic remains. Lawmakers, who spend a limited amount of time here and who need money to campaign with and money to live, find in Austin an environment in which money is everywhere and good times are on hand. Austin is a place to booze and get laid and get rich, if that’s what you want.

The state of Texas has built a political system that is effectively designed to produce petty grifters, which it succeeds in doing with great regularity.

As late as 1989, businessmen were still wandering around the floor of the House and Senate with checkbooks in hand, as East Texas chicken magnate Lonnie Pilgrim did when he sought to defeat a worker’s compensation bill. When asked about Pilgrim, Travis County District Attorney Ronnie Earle told the AP that “in Texas, it’s almost impossible to bribe a public official as long as you report it.” That’s what political scientists call “legal corruption,” and it’s the rule by which Texas operates.

It’s still the case today — the state has only the thinnest veneer of an ethics regime to disincentivize shady behavior. Lobbyists are easily able to hide their expenditures wining and dining lawmakers, and there are many ways to shift larger sums of money into lawmakers’ pockets. Lawmakers may be retained as “consultants” by deep-pocketed public and private entities, from school districts to payday lenders. Many who serve in the Legislature, like Uresti, are lawyers, and the public gets very little information about the legal “services” they’re providing clients.

Is there any state agency systematically pursuing the worst cases of conflict of interest or malfeasance by public officials? No, of course not. The last independent body really capable of doing so, the Travis County DA’s Public Integrity Unity, was defanged by the Legislature a few years ago — and it was never that good to begin with. Its responsibilities were handed to the Texas Rangers, an organization that’s not equipped to perform robust oversight and whose interests are not well-served by going to war with the lawmakers who oversee it.

Sometimes it’s said that this system is an accident, or that it’s broken, but it is not. It’s a choice. The system is working the way it is intended to work. It’s like that scene in Serpico where the corrupt cop attempts to force the clean cop to take money — any money — so that he’ll have bought into the system. Almost everyone there is at least a little bit compromised — it’s so easy to do — and that makes them pliable.

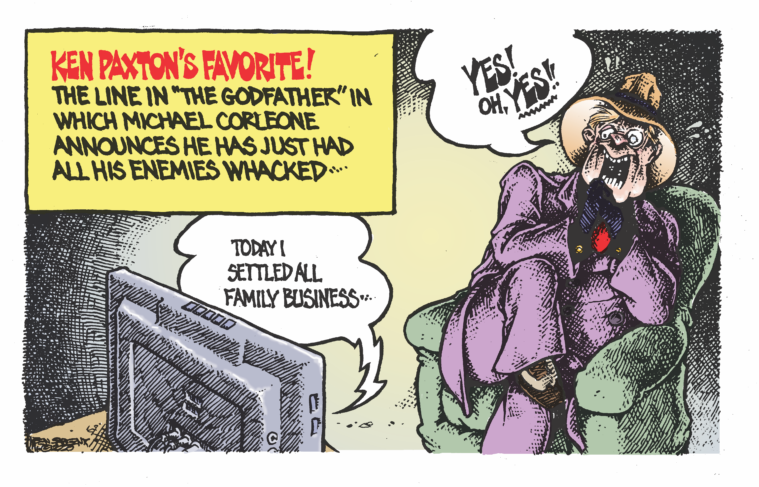

One of the elements of Uresti’s case, in which he convinced a legal client to invest money in a sham company he was getting kickbacks from, is very similar to the core of the case against indicted Attorney General Ken Paxton, who allegedly engaged in a number of other petty grifts when he served in the state House, too — shady real estate deals, investment in government contractors that seemed to get preferential treatment, etc. But Paxton’s case is stalling out, slowly strangled by a friendly legal system in Paxton’s home county. The most important factor in Uresti’s prosecution is that it was brought by federal prosecutors in a federal court. We protect our own: The feds don’t care. But the FBI doesn’t have the resources to do a proper sweep through the Texas Legislature — they’d be here for years.

There are good people in the Legislature, to be sure. But there are also a lot of bad people, and more importantly, a lot of middling people. We like to think our morality is hard and fast, but to an uncomfortable degree it’s the result of the incentives we perceive around us. In the Legislature, the incentives are all wrong.

Maybe Uresti was always a little off — that would be comforting to think. Or maybe, he wanted to do right, once upon a time, and then found himself in a job with power over others, access to ill-gotten gains, and seemingly no consequences — and marinated in it for 20 years. Maybe you’d find yourself in the same place.