In Houston, a Plan to Expand Interstate 45 Encounters Federal Pushback

For years, community groups have been organizing to stop a massive highway expansion. In March, the federal government paused the project, citing serious civil rights concerns.

A version of this story ran in the May / June 2021 issue.

When Modesti Cooper returned home to Houston in July 2019 after more than a decade overseas with the United States military, she moved into her dream house on the corner of Nance and Grove streets in Houston’s Fifth Ward. She’d bought a parcel of land and designed the home from scratch in her downtime while touring from Kuwait to Afghanistan to Iraq. It was a relief to finally move in. “It’s a calm, cool, nice area,” Cooper says. “Besides the traffic, there’s no violence, no noise. It’s so quiet, it’s unbelievable. I had rockets and mortars and missiles blown over my head. To come home to peace of mind and say, OK, this is my forever home.”

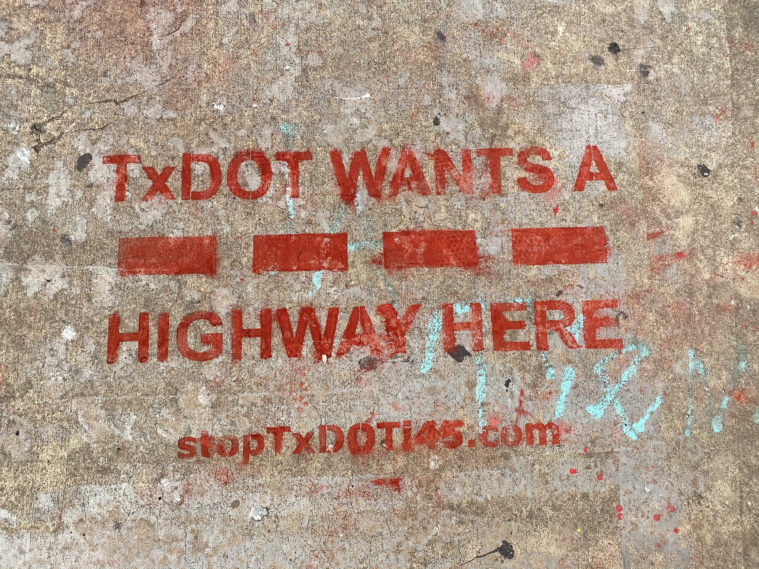

Cooper, 35, had barely unpacked when she started receiving letters from the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT). The agency was planning to expand Interstate 10 as part of the North Houston Highway Improvement Project: a $7.5 billion initiative to expand I-45 from downtown Houston north to Beltway 8 and rebuild and reroute parts of the downtown loop.

When Cooper started getting letters, the project was working its way through the years-long environmental review process required by the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA). The agency couldn’t yet compel Cooper to sell her forever home through eminent domain to make way for a new overpass. “At first, it seemed like they were going to work with me,” she says. “But once I actually got to the TxDOT office and met with everyone, it was more like: you’re going to lose your house. You might as well just give it up to us.”

Cooper refused, and in late February of this year, she filed a complaint with the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), a division of the U.S. Department of Transportation that oversees highways. In the complaint, she alleged that the expansion project violated Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which prohibits discrimination “on the basis of race, color, or national origin” in any project that receives federal funding.

Cooper, who is Black, lives in one of the only new homes on her block. Many of her neighbors are Hispanic and have been in their homes, built in the 1930s and ’40s, for generations. They know each other, have cookouts and holler across fences: “Where you going neighbor? What’s going on?” she says. TxDOT, she believes, could only see the old and rickety homes, not the lives and history inside them. “I just feel like, yeah, there is some sort of discrimination because you wouldn’t go to any other neighborhood like River Oaks and kick those people out of their homes.”

According to the final environmental impact statement published by TxDOT in August, the last step in the NEPA process, the project would displace 160 single-family residences, 433 multi-family residential units, 486 public and low-income housing units, 344 businesses, five churches, and two schools. TxDOT’s own analysis concluded that “the effects of the project would be predominantly borne by minority and low-income populations.” However, the agency continues to stress the benefits of the project—increasing capacity to reduce congestion and improving design to make the corridor safer, along with other improvements—and maintains that it would sufficiently mitigate any adverse impacts.

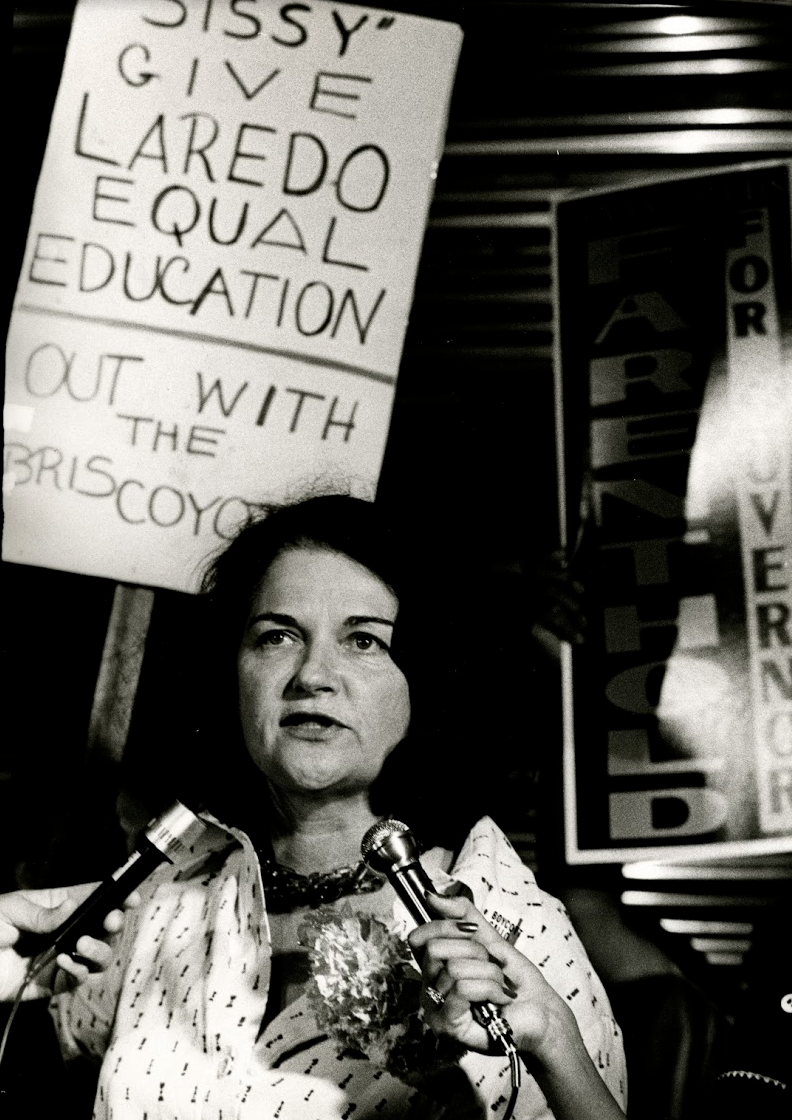

Community groups in Houston have been organizing for years to stop the expansion project. They’ve held protests and marches, called into city council meetings, and sent comments to TxDOT and the Houston-Galveston Area Council (H-GAC), which oversees transportation planning in Harris County. Gradually, Houston’s elected officials have started to sour on the project. In December, Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner sent a letter to TxDOT’s district engineer stressing that the highway shouldn’t be widened and threatened to pull the city’s support if the project’s “shortcomings” were not addressed. H-GAC requested a memorandum of understanding that would hold TxDOT accountable for mitigating adverse impacts of the expansion. TxDOT refused to sign it and instead insinuated that if Houston didn’t like the project, the agency would go ahead and take its $7 billion elsewhere.

In early February, TxDOT issued a record of decision, the end of the NEPA process which allows the project to move forward into construction. But by then, the tides had turned—and not just in Houston.

On March 8, the Federal Highway Administration sent a letter to TxDOT requesting that the agency pause activity on the project until the federal agency could investigate “serious” civil rights concerns. Days later, Harris County filed a lawsuit against TxDOT in federal court, alleging the agency had “ignored serious harms” and disregarded community concerns during a “flawed” environmental review process. A TxDOT spokesperson declined a request for an interview, but said in an email that the agency was in contact with FHWA and seeking clarity around what the pause meant for future contract solicitation efforts.

FHWA’s intervention in Houston is perhaps the first sign of a significant sea change in the U.S. Department of Transportation under Secretary Pete Buttigieg. Shortly after the former South Bend, Indiana, mayor was nominated to the cabinet position, he told CNN, “It’s disproportionately Black and brown neighborhoods that were divided by highway projects plowing through them because they didn’t have the political capital to resist. We have a chance to get that right.”

Houston is a test case for that commitment. Over the coming months, FHWA investigators plan to talk to community members, local officials, and advocates to determine, among other things, whether the highway expansion project “creates potential disparate, adverse impacts to the predominantly African American and Hispanic communities within the project area.” If the agency finds that discrimination occurred, it can refer the project to the U.S. Department of Justice to litigate or withhold some categories of funding allocated to Texas. More likely, the FHWA will try to mediate some kind of voluntary resolution with TxDOT.

“I think the really important thing is that it’s about whether there’s a disparate impact,” says Erin Gaines, an attorney at Earthjustice who has worked on Title VI complaints. “They may also be talking about intentional discrimination, but you don’t need intentional discrimination to violate Title VI in an administrative complaint. You need a disparate impact.” In other words, it doesn’t matter if TxDOT intentionally chose to expand a highway that runs through a predominately Black and Hispanic neighborhood; it only matters if Black and Hispanic people are unequally impacted by the highway being expanded.

“Many of these neighborhoods literally had no voice in the construction of this highway,” says Christof Spieler, the director of planning at the design firm Huitt-Zollars. When I-45 was completed in 1958, many “residents were not even able to vote for the government that was putting these projects in place.”

By the time the Voting Rights Act passed in 1965, most urban highways across the United States had already been planned and built.

The last time the FHWA came to Texas to investigate a highway project was in 2015, after residents of Hillcrest and Washington-Coles, two predominantly Black neighborhoods in Corpus Christi, alleged that a proposed rerouting of the Harbor Bridge violated the Civil Rights Act. In 2003, TxDOT proposed rebuilding the aging Harbor Bridge to address safety concerns and suggested moving it from the eastern edge of the harbor to an alternate route that would bisect the two neighborhoods. At the time, Hillcrest and Washington-Coles had significantly higher Black populations than the city as a whole—35 and 30 percent, respectively, compared to 4 percent of Corpus Christi as a whole. In 2014, TxDOT’s final environmental impact statement concluded that their proposed route for the Harbor Bridge would result in “disproportionately high and adverse effects to minority populations and low-income populations.”

In 1958, the construction of Interstate 37 south of the neighborhoods had isolated Hillcrest and Washington-Coles from the rest of the city, hemming them in with the industrial plants and refineries that had sprouted to the west. As the area became more and more polluted, besieged by explosions and chemical spills, people and businesses started moving out. In the early 2000s, about 1,500 families remained. Many felt fiercely connected to the community where they’d grown up and raised their families. “I think most of the folks knew that change was coming,” says Adam Carrington, the pastor at Brooks AME Worship Center in Hillcrest. “They just didn’t know it was a bridge that was going to be coming.”

In March 2014, residents filed a complaint with the FHWA alleging that the bridge project violated their civil rights. Nine months later, TxDOT agreed to a voluntary relocation program for residents. Those who qualified could get reimbursed significantly more than the market value of their homes, which had been devalued over decades because of the environmental degradation around them.

In some ways, the agreement was a success. As TxDOT moved forward with construction on its preferred route through Washington-Coles, more than 300 families left the neighborhood and bought homes of much higher value in Corpus Christi or elsewhere in Texas. But many residents didn’t want to leave their community behind, and had instead advocated for the creation of what they called “Hillcrest 2,” an entirely new neighborhood away from the refineries and bridge where they could remain together as a community. “We had grown up together, we had been together all our lives. I wish that we could have as a group stuck together. I think we would have come along a lot better,” said Rosie Ann Porter, one of the plaintiffs in the civil rights complaint, in a documentary project about Hillcrest.

Residents’ requests to relocate together as a community were deemed untenable.

“This is a key thing: FHWA will negotiate any resolution agreement with TxDOT,” Gaines says. “The resolution agreement for the Harbor Bridge was not signed by community members.” So although community members were at the table during negotiations and voiced their preferences, it was on FHWA to take those preferences into account.

Isis Berruete grew up with her mom and six siblings in Kennedy Place, a 60-unit public housing complex on Gillespie Street, two blocks south of I-10 in the Fifth Ward in Houston. Their two-story brick home had two bathrooms—a luxury that made Berruete feel like she was rich. She walked to school at Bruce Elementary, a red-brick building in the shadow of the tangled spaghetti junction of I-10 and I-69.

In 2009, after Kennedy Place was demolished to be redeveloped into a 108-unit apartment complex, Berruete says her mom was given a Section 8 voucher valued at $500 a month and told she could come back when the new development was completed two years later. Unable to find a place big enough for the whole family, Berruete, who was 19 at the time, and her older siblings moved out on their own. “The same thing that is happening to Clayton Homes and Kelly Courts happened to me,” she says.

If it goes forward, the highway project would subsume all 296 units of Clayton Homes, a public housing complex built in 1952 and tucked in the armpit between Buffalo Bayou and I-69. It would also run through at least part of the 270-unit Kelly Village, formerly Kelly Courts, located across the highway. Last year, in anticipation of the highway expansion, the Houston Housing Authority (HAA) sold Clayton Homes to TxDOT for $90 million and said it would use the money to build two mixed-income communities which will “include replacement units specifically reserved for the displaced Clayton Homes residents, who will have the first right to return after construction is complete,” said Mark Thiele, the agency’s interim president and CEO, in a statement.

In the meantime, residents say they’ve been told they can either accept a Section 8 voucher, essentially a rent subsidy, or move to another property in the neighborhood. “We still don’t know where we’re going or how they’re going to handle it,” says a resident named Mike, who declined to provide his last name because he was worried that HHA wouldn’t give him a voucher if he spoke out—a concern shared by residents at both complexes. But a voucher doesn’t guarantee housing. In Texas, it is legal for landlords to decline to rent to voucher-holders, who are overwhelmingly Black and Hispanic. As a result, many families struggle to find adequate housing and end up moving to poor, predominantly minority areas, according to a lawsuit filed by the Dallas-based Inclusive Communities Project in 2017.

In addition to displacement, FHWA investigators can consider environmental justice issues like pollution. As a kid, Isis Berruete says she frequently got headaches, which she attributes to the air quality at her school, Bruce Elementary. “It was like a cloud everyday. My mind felt cloudy,” she says. “Now, I have issues with my throat, my esophagus, my glands, because of that air quality.” In 2019, a report by Air Alliance Houston found that students at Bruce Elementary—99 percent of whom are Black or Latinx and qualify for free or reduced lunches—suffered from asthma at twice the rate as other students in Houston Independent School District. Expanding I-69 could make the problem worse, the nonprofit found. Air Alliance Houston modeled air emissions at the school and found that bringing the highway even closer could cause substantial increases in traffic-related air pollutants like benzene, a chemical compound known to cause cancer.

The FHWA is beginning the process of interviewing impacted residents and may conduct site visits this summer, but it’s still unclear what residents will be able to demand and what outcomes TxDOT will entertain.

The investigation could prompt TxDOT to reconsider how it approaches highway projects in cities across the state—the agency has just begun the NEPA process for a $7.5 billion expansion of I-35 through Austin. But ultimately, change will have to come from the state legislature, which has required that 97 percent of TxDOT’s funding be spent on roads.

In the Fifth Ward, Modesti Cooper says surveyors have started marking lots on her street, wood sticks appearing in front yards fluttering with bright pink flagging tape. Two of her neighbors have moved out. She’s not going anywhere until she has to. “I can see downtown, I can walk to Discovery Green, to the bike trails and park that we paid our tax dollars for,” she says. “I won’t even get to use that if I have to leave this year. Now that we’re actually getting the things we want, it’s being taken away.”