In Mexico’s Historic Vote, Politics Are Little Changed

A Puente poll represents a rare survey of the Mexican public by U.S. media.

Editor’s Note: This story, republished here with permission, was co-published by the National Association of Hispanic Journalists’ palabra and Puente News Collaborative. Angela Kocherga, news director at KTEP public radio, contributed to the story. Haga clic aquí para leer el reportaje en español.

Crossing a historic threshold, Mexicans appear poised to elect a woman as president this Sunday but to otherwise leave politics largely unchanged.

Indeed, the vote won’t reflect hunger for a sweeping shift in the country’s direction that took place six years ago when high levels of corruption from state and federal authorities led voters to elect a new alternative, represented by Andrés Manuel López Obrador and his four-year-old political party Morena, according to a nationwide in-home poll commissioned by Puente News Collaborative, an El Paso-based non-profit organization.

In what will prove the largest election in Mexican history, nearly 100 million people—including millions living in the United States and elsewhere—are eligible to cast a ballot. In play are more than 20,000 local, state, and congressional posts.

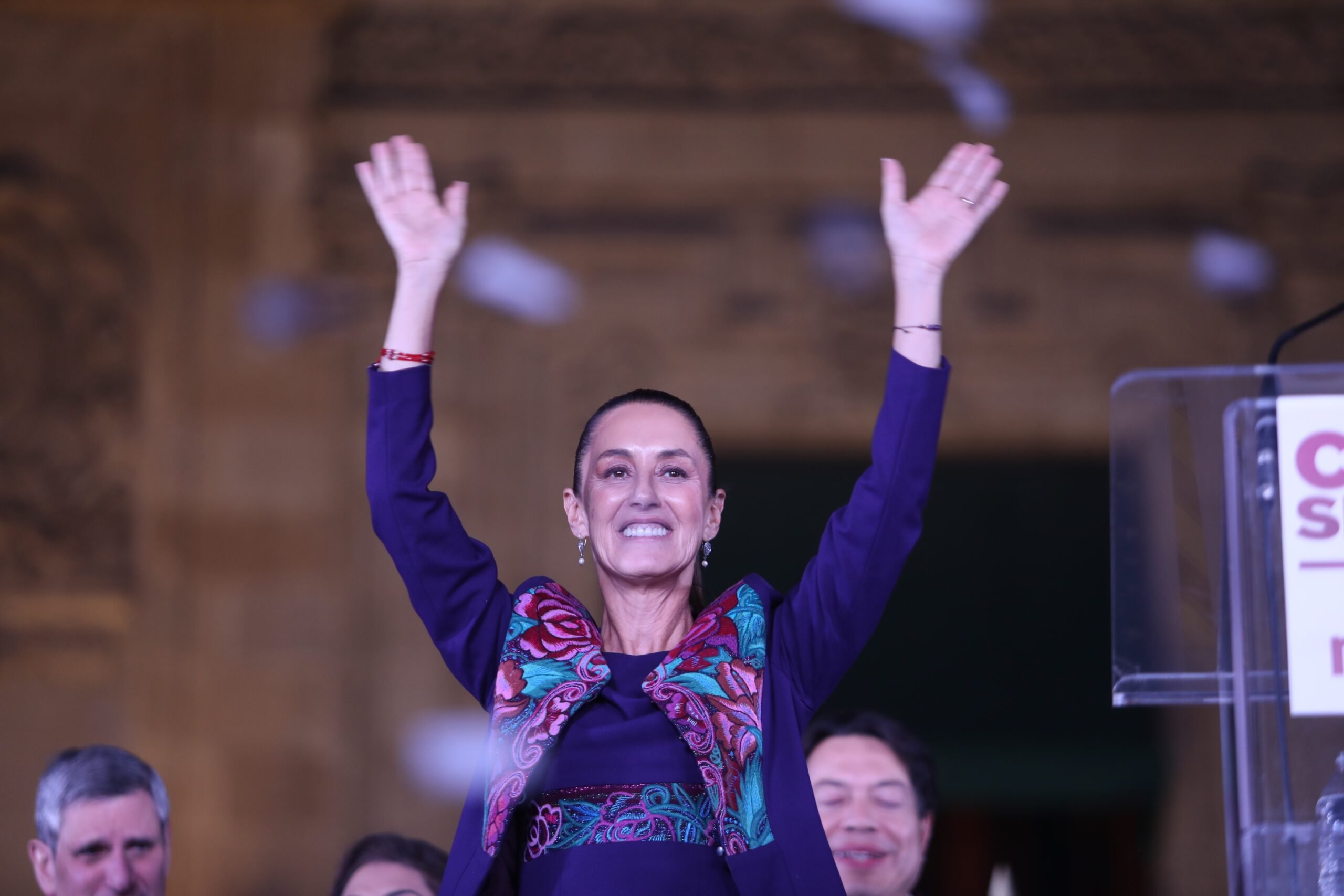

Claudia Sheinbaum, 61, is a physicist, environmental engineer and former Mexico City mayor who is ethnically Jewish in an overwhelmingly Roman Catholic society. Her likely election comes amid a deepening gangland grip on the country and widespread fears among political analysts and voters of a return to the autocratic rule that governed Mexico until the turn of this century.

In addition to political preferences, Puente’s survey gauges Mexicans’ attitudes toward their solid export-fueled economy, the often fraught ties with the United States and the millions of foreigners who have taken up at least temporary residence here, the most ever.

While concerned by the migrant influx, more than two-thirds of poll respondents said the migrants should be given temporary work permits even as the government tightens control of the borders and the human flow.

Yet, if the Puente poll and an array of others prove accurate, most Mexican voters will opt for the status quo.

“There seems to be a certain complacency, social resignation—a certain lack of (the) urgency that a few years ago really ignited Mexicans,” said Carlos Bravo, a Mexican political analyst and frequent critic of the governing party. “What we’re seeing is that the Mexican people are behaving as if they had no power to demand and to expect a better government.”

The Puente poll—conducted by Mexico City’s Buendia & Marquez firm and funded in part by the Center for the U.S. and Mexico at Rice University’s Baker Institute and UC-San Diego’s Center for U.S. Mexican Studies—represents a rare survey of the Mexican public by U.S. media. The poll interviewed 1,000 demographically diverse people and was slightly skewed to areas nearer the U.S. border. It has a margin of error of +/-3.5 percent.

The survey gives Sheinbaum as much as 54 percent of the vote, after eliminating undecided or voters who declined to answer the survey. Center-right candidate Xóchitl Gálvez garners 34 percent while 12 percent of respondents favor center-left candidate Jorge Álvarez Máynez from Movimiento Ciudadano. That portion of the survey was the Mexico daily, El Universal.

Mexico’s national election this year—as it does every dozen—coincides with the U.S. presidential vote.

Overall, Mexicans have a favorable view of the United States, particularly the Americans who are increasingly moving to Mexico either to retire or work remotely. Those recent arrivals so far are undeterred by a 23 percent strengthening of the peso against the U.S. dollar in the past five and half years.

Most respondents in the Puente poll judge Sheinbaum most capable of dealing with the U.S. relationship. The poll suggests that 69 percent of Mexicans believe Joe Biden would prove better for Mexico, compared with just 11 percent saying that about Donald Trump.

“Elections in Mexico don’t worry me much, because nothing really changes,” said Miguel Vargas, 68, a taxi driver in Ciudad Juarez, which borders El Paso. “What I’m really worried about is Trump coming back to office. I’m scared he’ll shut down the international bridges and that will kill us financially.”

Mexico last year overtook China as the largest U.S. trading partner. Nearly $800 billion worth of products were traded in 2023, the largest sum between two nations anywhere, according to U.S. trade figures.

Texas, California and Arizona take the lion’s share of that business. But binational trade is deepening into the U.S. industrial heartland—particularly in Illinois, Michigan and Wisconsin.

Legally limited to a single term, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, 70, has strongly backed Sheinbaum, his hand-picked candidate. She, in turn, vows to deepen his nationalist-populist agenda—the so-called Fourth Transformation, or 4T, that has created different cash-transfer programs for the poor, mainly for the elderly, students, farmers and kids with disabilities. That agenda seeks to replace many market-friendly policies of past presidents, like the opening of the energy sector to private capital.

Xóchitl Gálvez, also 61, a conservative businesswoman and former federal senator, leads a triple alliance of centrist political parties that dominated politics until López Obrador’s 2018 election.

Gálvez’s candidacy perhaps has stolen the import of Sheinbaum’s gender-breaking moment. But Mexican women have greatly increased their political participation. Reforms a decade ago mandate that women comprise half of candidates vying for local, state and federal office.

For many voters, this election stands as a referendum on López Obrador. His Morena party, which he founded barely a decade ago, now holds the majority of Mexico’s national Congress, two thirds of its 32 governorships and a significant portion of Mexico’s nearly 2,500 municipalities.

Many critics fear the president—widely known by his initials, AMLO—intends to rule from behind the scenes. In interviews with Puente, analysts and voters said the election may decide whether the country persists in its stumbling search for full democracy that began 30 years ago.

“It’s not so much about two women, but about a stubborn old man,” said Gerardo Contreras, 58, a Mexico City barber. “People forget how far we have come only for our leaders, particularly López Obrador, to send us backwards.”

Neither of the leading candidates’ ethnicity has played much of a role in the campaign. Sheinbaum, whose ancestors fled the Holocaust, has said she was raised in a secular left-leaning household. Gálvez grew up poor as the daughter of an indigenous Otomí father and mixed race mother and worked her way through university.

But Gálvez’s three-legged coalition includes once-prominent and now widely discredited political parties. The Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) held the presidency for most of the past century but its return to the presidency in 2012 proved disastrous.

Gálvez’s center-right National Action Party, which ended the PRI’s political grip in the 2000 elections, largely underwhelmed Mexico in the 12 years it held the presidency. Weakest of the three, the Democratic Revolution Party, was the country’s main leftist movement until López Obrador siphoned away its supporters.

Voters interviewed by Puente say insecurity remains a primary concern. But they see no immediate end or viable solution to it. Violence simply has become part of daily life for the country’s 130 million people.

Once fueled by narcotics trafficked to U.S. users, criminal violence has risen sharply in the two decades since presidents from Galvez’s PAN party launched a military-led campaign against the criminal organizations and that president Felipe Calderón called the “war on drug cartels.”

Hundreds of thousands have been murdered and many thousands more disappeared and presumed dead. Extortion, fuel theft, human smuggling and other rackets have replaced narcotics as sources of gangster income.

Although he’s kept the military in the fight, murders have averaged about 30,000 a year under López Obrador, making his the bloodiest administration this century. Despite that, the president enjoys a 70 percent approval rating, according to Puente’s poll, suggesting he’s largely escaping blame for the violence.

López Obrador leaves office October 1.

The gangsters’ sway in politics, especially at the local and state levels, is reflected in the assassinations that have stained this year’s campaigns. Some three dozen candidates from all parties have been killed. Scores more have dropped out of their races out of fear.

“Violence has become a normal thing for us,” said Alejandra Ornelas, 28, a factory worker in Mexicali interviewed by phone. “These days you just never know where you may find bodies on the way to work. Maybe on the road, or next to a canal. There needs to be punishment.”

Still, Ornelas said, Sheinbaum was getting her vote.

“Because of the money Morena gives to help us,” Ornelas explains, nodding to the cash handouts and other subsidies to Mexico’s neediest, a bulwark of López Obrador’s policies.

Elsewhere along the Mexican side of the U.S. border, some poll respondents went silent when the conversation turned to the criminal threat.

“Answering that question can get us killed,” explained a voter in Reynosa, an industrial city across the Rio Grande from the South Texas city of McAllen.