On a Wednesday morning in April, the Heidi Clinic is empty, save for a few staff members. Suddenly, an automated voice breaks the quiet: “Motion detected.” Faint footsteps grow louder as the alert sounds again. “Motion detected: hallway.”

Carol Everett emerges into the waiting room, where a light purple wall is painted with bright pink letters spelling “Heidi Clinic” — named for the daughter Everett would have had if not for the abortion that she says ruined her life. Everett, 74, a prominent anti-abortion activist, is dressed in black with a floral top and large silver cross around her neck. She leads me from the reception area, where she directs the staff in prayer each morning, past empty exam rooms and the nurse practitioner’s office, where quotes such as “A child is a story waiting to be told” are painted on the wall. At the end of the hall is Everett’s office. “Pro-life today, tomorrow and forever from conception to natural end…” is typed across a photo of her giving a speech. On a bookshelf is a copy of the Bible. Just under it, there’s a binder with “Evangelism Explosion” along the spine, and a sign that reads “Talk less! Pray more!”

The state of Texas has poured hundreds of thousands of taxpayer dollars into Everett’s clinic, which opened in a strip mall in Round Rock last spring, and millions through her anti-abortion organization, the Heidi Group. Everett’s group was tapped as a test case in the effort to defund Planned Parenthood and lift up faith-based, anti-abortion clinics in state and national family planning programs. It didn’t go well. In October, the state announced it would end Everett’s funding, two weeks after the Observer reported that the group had served just 5 percent of the patients promised in its first year.

Now, internal documents, communications and financial statements obtained by the Observer, along with state records and interviews with half a dozen former Heidi Group employees and with Everett, paint a picture of mismanagement, contract violations, lack of oversight and misuse of taxpayer funds — problems that state officials knew about even as they continued to extend the Heidi Group’s contract for more than two years.

After her abortion at 28, Everett — who has called Jesus Christ “the ultimate unplanned pregnancy” — ran Dallas-area abortion clinics for about six years until she “came to Christ” in the ’80s. In 1995 she founded the Heidi Group, a nonprofit that supports religious crisis pregnancy centers, which counsel patients against having abortions. “If we bring [a woman with an unwanted pregnancy] to the saving knowledge of Jesus Christ, we’re saving two lives,” she said in a 2009 interview.

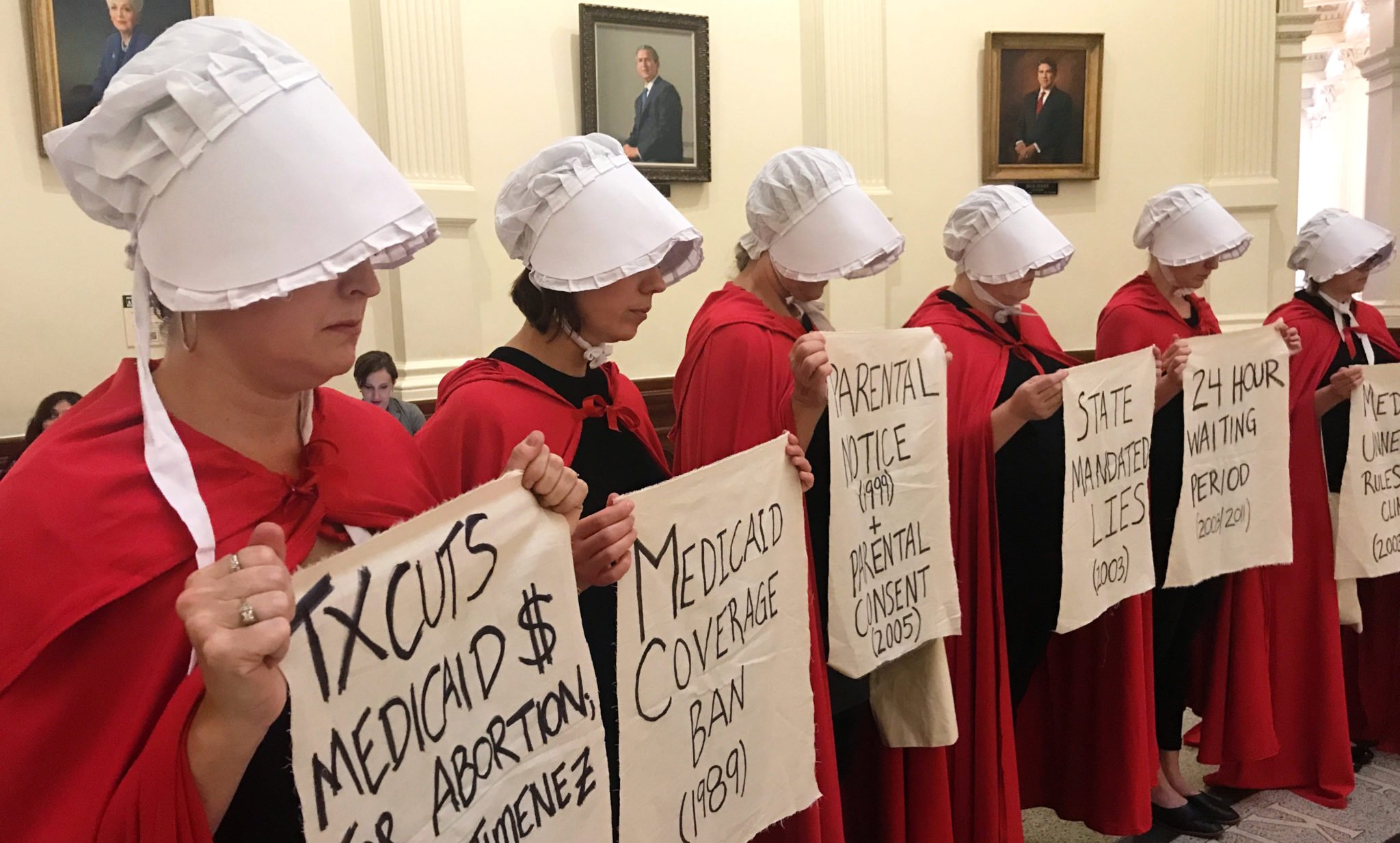

State lawmakers have funnelled millions into the kind of clinics that Everett has championed. The budget for Texas’ Alternatives to Abortion program, which funds faith-based pregnancy centers, has grown 16-fold since its inception in 2006, following this legislative session, with a total investment of about $170 million through 2021. In 2011, Republican lawmakers slashed the state’s family planning budget by two-thirds, shuttering 82 clinics. Two years later, they kicked Planned Parenthood and other abortion provider affiliates out of the state’s low-income women’s health program, forgoing millions in federal dollars to begin a state-funded program instead. At the time, less than a quarter of the estimated 1.8 million poor Texas women in need of publicly funded contraceptive services were getting them. The cuts resulted in tens of thousands more women losing access to reproductive health services like gynecological exams, birth control, cancer screenings and STD testing.

Then, in 2016, the state’s goals and Everett’s aligned in what she called “the greatest possibility for expansion of pro-life care for the poor ever.” Texas’ health agency had scrambled for years to rebuild the reproductive health care safety net without established family planning providers like Planned Parenthood. Now, the Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC) was launching a replacement program called Healthy Texas Women, which would provide reproductive health care and preventive screenings to low-income women. Officials needed someone to fill the gap left by Planned Parenthood, which had previously served 40 percent of patients in Texas’ women’s health program.

Everett had no experience with state family planning programs. But officials awarded her multimillion-dollar contracts to find and oversee providers in Healthy Texas Women and in the Family Planning Program, the state’s other reproductive health program that also covers men and undocumented patients. Everett pledged to serve an astounding 69,000 patients in the two programs during her first year — more than Planned Parenthood.

The experiment failed dramatically. For fiscal year 2017, the Heidi Group was awarded $1.6 million to serve 51,000 patients in Healthy Texas Women; it spent $1.3 million and served 2,300, according to HHSC data. In the Family Planning Program, the group got $5.1 million to serve nearly 18,000 people. After realizing the Heidi Group was falling short of those targets, the state clawed back and reallocated funds mid-year. It ended up spending $605,000 to serve just over 1,000 patients. HHSC released data for fiscal year 2018 in May, but did not specify the number of patients served by contractors. According to an Observer analysis, which added the patients served by Heidi Group subcontractors and the Heidi Clinic in each program in 2018, roughly 4,000 patients were served through Healthy Texas Women and about 2,700 through the Family Planning Program. The state ended Everett’s contracts in December, and launched an investigation into more than $1 million in questionable spending. Her own clinic, which has served just a few hundred women, faces an uncertain future.

In May, the Texas Legislature further defunded Planned Parenthood. Having already blocked abortion providers and their affiliates from the state’s women’s health program and tried to kick them out of Medicaid altogether, conservative lawmakers banned local government entities from partnering with these clinics, pointing to the long list of Healthy Texas Women providers as evidence that others can fill the gap. But opponents of Senate Bill 22 cited two pieces of evidence first reported by the Observer to refute this: that almost half the Healthy Texas Women providers didn’t see a single patient in the program in 2017, and that the Heidi Group served less than 5 percent of the patients promised, according to state data.

“It’s 2019 and we’re still rebuilding a program we decimated,” said state Representative Donna Howard, an Austin Democrat. “You’re sacrificing women and their health to achieve a political agenda by shutting down Planned Parenthood … I’m totally blown away … that we continue to do this.” State Representative Sarah Davis, a Houston Republican who supports abortion rights, cited the Heidi Group’s failure in her argument that the Healthy Texas Women program “has been riddled with problems.” Other contractors also had funds clawed back for missing their targets, though none as dramatically as the Heidi Group. “Who will fill the gap if we pass this law and Texans lose even more access to care?” Davis said on the House floor. “The answer is very simple: no one.”

The Heidi Group’s quick rise and fall is a cautionary tale of what happens when government prioritizes politics over proven health providers. It also speaks to a growing national effort under President Trump, following Texas’ example, to divert funds away from established health providers and toward anti-abortion, often religiously affiliated organizations like the Heidi Group. More than 20 states have sued to stop Trump’s proposed changes to the federal Title X program that would block funds to providers that perform or refer for abortions. The impact would be sweeping: Planned Parenthood alone sees about 40 percent of patients who get family planning services through Title X.

The collateral damage is poor women, who are losing access to care. “When [Texas] gambled that a new and untested provider, who didn’t have any history in these programs, could go from zero to 60 miles per hour overnight, they took money away from other experienced and knowledgeable and efficient providers to do that — to run that experiment,” said Stacey Pogue, an analyst at the left-leaning Center for Public Policy Priorities who previously worked on women’s health programs at HHSC. “So when the state allocated money to this provider that could not perform on their contract, and there were red flags all along that that was going to happen … yet their contracts were renewed and renewed, that ties up money in the system,” she said.

“There’s an actual harm. There are women who weren’t seen because providers ran out of money.”

The state awarded Everett her contracts in the summer of 2016 in an unprecedented arrangement. Her nonprofit didn’t actually provide health services. Instead, it was supposed to act as a kind of umbrella group, subcontracting with about two dozen providers that it would oversee in the two health programs. The idea was to help build a new network of family planning providers while easing the administrative burden on HHSC and on doctors by tasking the Heidi Group with oversight, outreach, marketing, training, web support and billing.

Everett assembled a group of private physicians and health clinics, some of which mirrored her mission. Several didn’t initially provide contraception, including Life Choices, a faith-based pregnancy center in San Antonio. As medical director for the Heidi Group, Everett tapped Noreen Johnson, an OB-GYN and fellow abortion provider turned anti-abortion activist, who she paid nearly $9,000 per month in state funds. Johnson’s clinic, located in the building of a now-shuttered Planned Parenthood in Bryan, was also a Heidi Group subcontractor.

Everett has long said her goal is to provide family planning services in rural areas. She argues that private physicians should be the ones doing so, not “abortion provider look-alikes” — that is, providers like Planned Parenthood that have been in state health programs for years. “People who provided this in the past have been on the abortion side,” she said. “They knew how to set up a system that works, and our guys didn’t. … Planned Parenthood has a system in place — like McDonald’s. And it works. Our people didn’t have a McDonald’s look-alike system.”

Abortion providers are not fast-food franchises, of course, and taxpayer funds are banned under federal law from covering abortions. But Everett’s argument, ironically, echoes that of reproductive health advocates, who say that established providers with experience in state family planning programs can operate more efficiently and effectively. In 2017, Everett said that meeting her targets is “not as easy as it looks, because we are not Planned Parenthood.”

But given the state’s antagonism toward Planned Parenthood, a contractor like the Heidi Group could have helped doctors navigate the new system. It could have helped providers serve more patients by streamlining the nonmedical responsibilities that come with participating in a state health program. But lacking staff and familiarity with the state’s accounting system and eligibility process, the Heidi Group didn’t follow through on its promises.

“We were basically a billing entity,” said Leslie Willkom, who worked at the organization for nearly two years. “I don’t know how they justified giving money to the Heidi Group, because every single subcontractor could have just contracted with the state; we didn’t need to be the middleman.”

Willkom, like other employees I spoke with, describes herself as a Christian with “pro-life beliefs.” She was drawn to the Heidi Group’s stated goal of providing reproductive health services to poor women. Willkom says she started working for Everett, who she met at church, as a volunteer in the spring of 2017, then was hired on a couple months later as the community outreach specialist. But she left the group this March, one of at least 10 staff departures over the last year or so, many of whom cited a hostile work environment in interviews and resignation letters. The Observer spoke with six former Heidi Group employees who worked in different roles over the last few years. Three requested that their names not be included.

“It’s like a cult,” said Willkom, who went to work for Everett “because I truly believed she was helping women. … Then I left and it’s like my eyes opened and I’m thinking, ‘What the hell just happened, what did I do?’”

“Millions of dollars were funneled through there, and we only helped a handful of women,” Willkom said. “That’s sinful, to take that amount of money and not use it for what it was supposed to be used for.”

In early 2018, Everett opened the Heidi Clinic. On top of the more than $65,000 in fee-for-service claims, state dollars paid for much of the clinic costs, which included rent that totalled more than $80,000 its first year; the $2,500 monthly salary for the clinic’s off-site medical director; equipment and office supplies; Everett’s salary and payroll for clinic staff whom one employee said were often “doing nothing, spinning our wheels.” The clinic served 345 people in the two state programs during fiscal year 2018, according to new state data, at an average cost of several hundred dollars per patient.

Phyllis Everette has been sharing information about the Heidi Group and what she calls its “gross misuse of taxpayer dollars” with HHSC officials since last summer, when she was fired from her role as program director. Everette, who has no relation to Everett, filed a complaint with the Texas Workforce Commission last June. “My prayer is for less of a hostile work environment,” Everette wrote in the complaint, regarding an alleged dispute during morning devotion, adding that Everett “used bullylike tactics by threatening anyone who wanted to challenge her.”

Shortly after, Everette reached out to HHSC officials to share information about the Heidi Group. She spoke with someone from the agency a few days later, shortly before it sent a letter to Everett identifying serious problems found in an audit that spring. In late July, an investigator with HHSC’s Office of Inspector General (OIG) emailed Everette to say he was looking into her allegations and wanted to meet. Less than two months after that, HHSC announced the OIG’s ongoing investigation into the Heidi Group’s spending, based on the audit.

Everett acknowledges that she didn’t do what she set out to. “I was ambitious, I admit that,” she told the Observer. “I thought it would be easier than it was, I don’t deny that.” But she deflects most of the blame — to providers, to staff, and most of all to the state, which she says “throws you in the water.” The yanking of the Heidi Group’s contracts has created a rift between former allies, with HHSC aiming to break ties and minimize its role in the contracting failure. Meanwhile, six months later, it’s still unclear who will fill in to reach the tens of thousands of patients the Heidi Group was supposed to serve.

That the Heidi Group failed to meet its goals should not have come as a surprise. Documents first reported by the Houston Chronicle show that HHSC officials were warned, even internally, against awarding the inexperienced organization such a substantial contract. They forged ahead anyway. Eight months in, the Heidi Group had not completed promised patient outreach, according to the Associated Press. After the Heidi Group served just a fraction of the patients promised, the health agency clawed back some money, but renewed the group’s contract. After an audit last year found contract violations and mismanagement of taxpayer dollars, the state renewed its agreement for a third year. Less than two months after that, HHSC announced it would end the Heidi Group’s contracts.

Despite the organization being new to state programs and receiving the second-largest Healthy Texas Women contract, HHSC didn’t conduct a financial audit of the group until a year and a half in, after similar evaluations of other contractors, records show. Everett calls this her organization’s “first help” from the state.

In July 2018, HHSC officials sent a letter to Everett detailing their findings of the financial review, which covered September 2017 to April 2018. According to the agency, during its first year and a half in the programs, the Heidi Group had failed to officially contract with its subrecipients, paid questionable or undocumented funds to those providers and charged tens of thousands of dollars in inappropriate expenses to the state grants.

Another HHSC audit, focused on clinical and program requirements during the same time period, found that the Heidi Group had minimal monitoring of its subcontractors. The Heidi Group’s “proposed quality assurance plan appears to put subcontractors in charge of their own quality assurance review,” cautioned the review report, dated October 11, 2018 — the day before HHSC announced it would end the organization’s contracts.

Everett said she had “oral agreements” and “handshakes” with her subrecipients for the first year. She claimed there were written agreements by the time HHSC auditors visited in April 2018, but staff accounts, draft contracts and HHSC reports indicate that the contracts were written later, and backdated two years. According to HHSC spokesperson Christine Mann the agency received signed subcontracts from the Heidi Group with effective dates of July 1, 2016 — but on July 11, 2018. Following the audit, HHSC “provided extensive technical assistance and outlined expectations and requirements over the monitoring of subcontractors,” Mann wrote in an email.

Of this lack of oversight, the CPPP’s Pogue said: “The state is wondering about Heidi Group’s controls. What are the state’s controls?”

There’s reason to think state officials knew of the lack of formal contracts long before the audit. In the first months of its Healthy Texas Women contract, one of the Heidi Group’s main providers, a Dallas-area nurse practitioner named Sherry Tenison, contacted HHSC about late payments from Everett. Shortly after, Everett emailed Tenison to call off their agreement. Tenison’s office forwarded Everett’s note, which had the subject line “Termination of oral contract,” to HHSC officials in January 2017.

More than a year later, just after the HHSC audit in April, Everett contacted Tenison about signing a contract for the period they worked together. “The State demands a contract for the time you received payment,” Everett wrote in the letter dated May 2018. “I have no other choice, Sherry. I would rather not continue in court or demand repayment from you.”

Meanwhile, checks show that Everett was paying some providers as much as $15,000 per month, apparently without a contract or guidelines in place. Under the Family Planning Program, subcontractors would bill for patient claims through the Heidi Group, which would cut them a check, Everett says, but under Healthy Texas Women, the doctors and clinics would bill directly. On top of the service payment, the Heidi Group gave its subcontractors $50 per patient claim to cover overhead costs. The $50 was supposed to be broken down into set fees for supplies and personnel, but in practice amounted to a flat charge per patient. “We just took however many patients they had and cut the check,” said Willkom. There “were no receipts to match up against.”

Under this arrangement, the state was essentially paying for services by Heidi Group subcontractors three times: for the actual service itself, for the Heidi Group’s contracted outreach and administrative work and for the additional $50 per claim, which would have totaled several million dollars if the Heidi Group subcontractors actually served their intended number of patients.

These $50 charges made up about a third of the nearly $670,000 in “unsupported” expenses HHSC identified during the seven-month audit. As part of the ongoing OIG investigation, Everett asked all the Heidi Group subcontractors to sign affidavits verifying the charges. Most participated, she said, but one she “couldn’t find,” and two “didn’t cooperate.” One of the latter, she added, “refused to cooperate because he wanted more money to cooperate.”

Willkom, who says she drafted the provider affidavits before she left, said her employer’s recordkeeping was scattershot at best. “It was such a mess that when the state came back and wanted proof of all these expenses, it was a nightmare trying to get proof. Because there isn’t any.” She added that Everett will “blame the state and say the state didn’t tell her, but you know what? That’s simple accounting. I’m not going to pay the electric company just because they call and say, ‘You owe X amount of money.’ I want a receipt.”

In the seven-month period of the audit, HHSC also identified more than $29,000 in disallowed charges by the Heidi Group, which have since been paid back. These include attorney services and payroll costs that occurred outside the period they were billed, plus nearly $9,000 in expenses deemed unrelated to the grants: travel, meals, appliances, gift cards and a couple hundred dollars for women’s dresses at Dillard’s.

“Let me tell you what that was: We had an employee that dressed very provocatively. I took her shopping,” Everett said of the Dillard’s charge. “Somehow that was an accounting error that was billed.”

But former employees say it was standard for Everett to arbitrarily charge expenses to the state. “Carol spent money like it was water,” said Elsie Cyrs, who worked on provider enrollment at the Heidi Group for about two years. Cyrs said Everett “didn’t have any records, or they were just sloppy.”

Everett gives many explanations for why her organization so missed the mark. Her primary complaint is that HHSC didn’t give her support. “We’re out there drowning, and we’re not getting any help,” she said. “The programs are great, but very difficult to manage.”

She claims that the state data undercounts the number of clients served by her clinics, that she’s “not getting credit” for patients that she says should be counted under the Heidi Group’s contract. But even Everett’s own numbers fall significantly below her contract targets.

Mann insists that HHSC’s data is accurate. Additionally, “The Heidi Group had substantial deficiencies in the areas of contract compliance, service administration, and financial and administrative management of both contracts,” Mann wrote in an email, responding to Everett’s criticism of the state. “We provided extensive technical assistance and conducted multiple reviews of the Heidi Group’s work over time,” but ultimately, terminating the contracts “was in the best interest of the state and the clients we serve.”

Everett defends the Heidi Group’s performance, saying that state officials told her it would take about four years to be successful with the program. “It was a start-up,” she said. “We had never done this before.”

But with more than a quarter of Texas women of childbearing age uninsured — the highest rate in the country, according to a recent report — and millions more nationwide in need of preventive screenings and contraception, advocates argue funds should be given to proven providers. “On a state level and a national level, we have never funded these programs to meet the need; we’ve always funded them to meet a tiny fraction of the need,” Pogue said. “Until that’s not the case, we need to prioritize giving money to providers in communities where there’s lots of women in need, where they’ll provide services today — not five years from now, not two years from now.”

Meanwhile, Texas’ effort to kick Planned Parenthood out of Medicaid completely is still tied up in court. Everett’s attorney during the OIG investigation is Stuart Bowen, the former HHSC inspector general who led the charge to eliminate Planned Parenthood until he was forced to resign last year. If Bowen’s effort is successful, it would dramatically cut access to reproductive health services for poor Texans, and lead the way for other states to do the same. A similar concern surrounds Texas’ negotiations with the Trump administration over a waiver to get the federal funding back for Healthy Texas Women that the state lost by kicking out Planned Parenthood. If successful, other states might feel empowered to pursue similar cuts.

Building up “startups” is more expensive, Pogue said, but if funding Planned Parenthood is off the table politically, the state needs “a dedicated thought process of how to raise up new providers to fill the shoes over time. It’s not something that happens overnight, just because you appropriate the money.” While Texas has invested money back into women’s health, she says that fewer people have access to care than did in 2011. “I don’t think the state has a pathway to get from startup to quality family planning.”

Meanwhile, women’s health advocates worry state officials will learn the wrong lessons from the Heidi Group’s failure. New budget language leaves it up to HHSC whether to continue with Healthy Texas Women contracts that provide funding for expenses outside of direct patient care. “We heard from our coalition members that are providers and contractors that [cost reimbursements] are really important to their infrastructure, to keeping their doors open,” said Erika Ramirez, a policy and advocacy director at the Texas Women’s Healthcare Coalition who previously worked at HHSC. “We hope HHSC will continue that, but with more oversight, safeguarding, being better stewards of taxpayer dollars.”

In January, just after the end of her state contracts, Everett applied for Title X federal family planning funding, according to the Houston Chronicle. Advocates worried that Trump’s proposed anti-abortion Title X priorities would favor the Heidi Clinic, again directing money away from providers with proven experience in the federal program. The application angered former employees who said it was full of lies; namely that it claimed the clinic sees 100 patients per week, listed several former employees who haven’t worked at the organization in over a year and didn’t mention the canceled contracts in Texas. Everett’s bid for Title X funding was unsuccessful, but groups like hers did get funding. The Obria Group, a Catholic organization that has refused to provide contraception, won a Title X grant in California, a potential harbinger of what’s to come across the country.

When I return to the Heidi Clinic in May, a month after my first visit, hardly anyone is there. The nurse practitioner and the medical assistant have both left. A job posting on the clinic’s Facebook page seeks a new nurse practitioner to work just one day a week, on Thursdays.

Everett won’t say how many patients the clinic sees now that the state grants are gone, only that it’s “less than it was.” In the several hours I spent there over two days, I never saw a patient. One exam room has been repurposed to store piled boxes of records, labeled “HTW,” “FPP,” “Audit.”

Private donations are keeping the doors open for now, says Everett. She “wants to be here to tell women the truth” about pregnancy and contraception. She shows me an ultrasound machine, a gift from a donor. “I love this piece,” she says, smiling. The state women’s health programs that funded the clinic itself are not intended to cover pregnant women — the focus of these programs is on birth control and preventive screenings. But it’s evident that Everett’s previous work with pregnancy centers still motivates her. She tells me about a woman who came to the clinic with an ectopic pregnancy in her fallopian tube. The unviable, dangerous pregnancy was found on this ultrasound machine, which Everett calls “a blessing.” So she got an abortion? I ask. “She was given the drugs to take the life of the baby,” Everett says. “It was a choice of her life or the baby’s life, and it’s the mother’s life, always.” She adds: “Saving her fertility will keep me going a long time.”

Editor’s Note: This story originally stated that HHSC announced it would terminate Heidi Group’s contract in September 2018. In fact, the announcement was in October. The Observer regrets the error.