In ‘Loving,’ a Valentine to Marriage Equality

Jeff Nichols' new film takes a quiet, deeply personal approach to telling a political story.

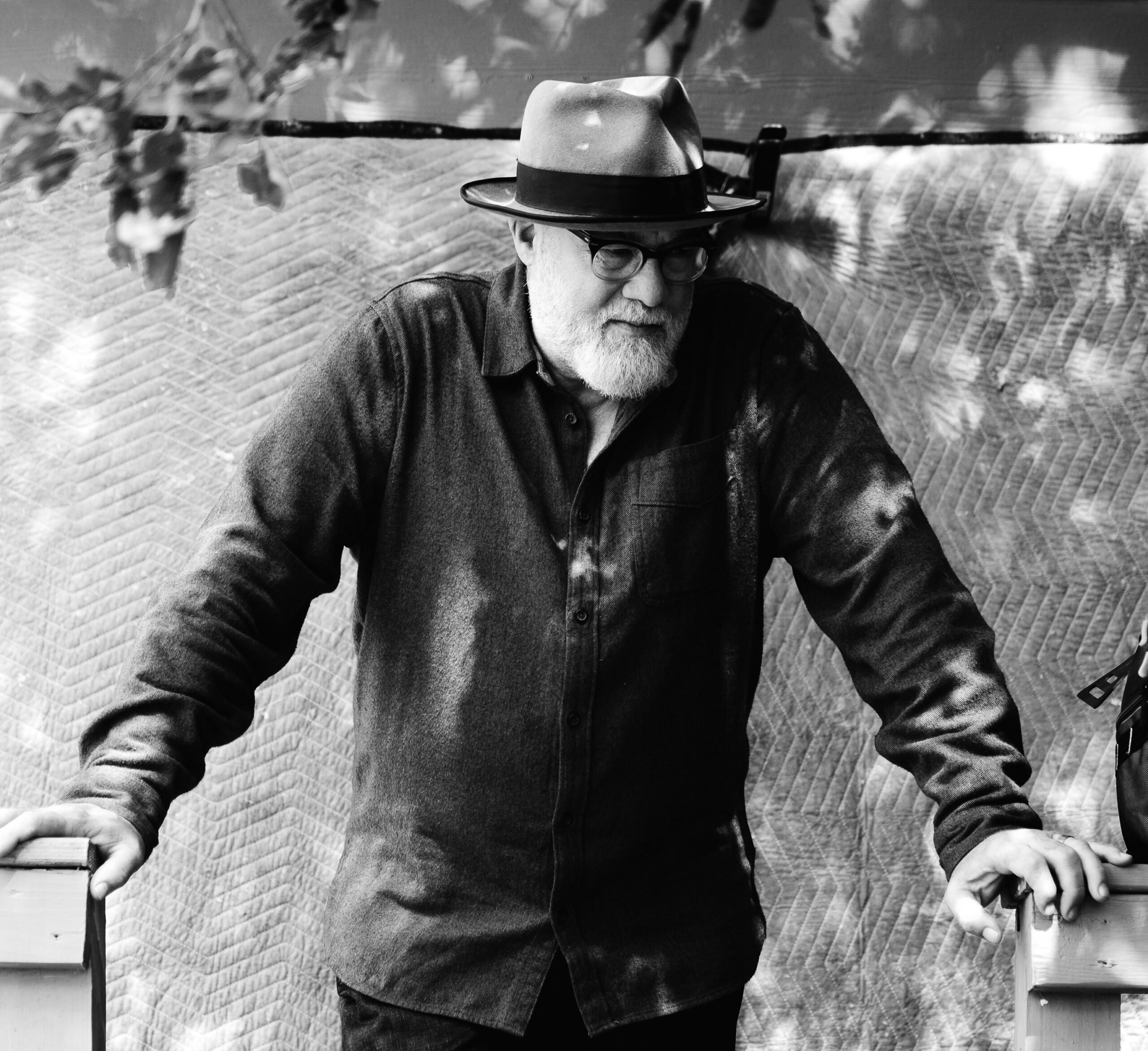

Austin-based filmmaker Jeff Nichols is best known for telling arthouse stories that push the boundaries of everyday reality—from the comic-book sci-fi of Midnight Special (2016) to the magic realism of Mud (2012) and the apocalyptic visions of Take Shelter (2011). So it comes as a charming surprise that his latest feature, the civil-rights-era drama Loving — opening Friday — is a study in character-driven restraint.

To begin with, Nichols sought out two lead actors, Joel Edgerton and Ruth Negga, who physically resemble Supreme Court plaintiffs Richard and Mildred Loving, the couple whose interracial marriage was the first to be recognized in all 50 states. He shot on location in rural Virginia, in the same county where, in 1958, the Lovings were arrested in bed together and sentenced to 25 years in prison. (The judge suspended the sentence so long as they self-deported to the more accepting confines of Washington, D.C.) Beyond his allegiance to visual verisimilitude, Nichols also strives to avoid giving the path-breaking couple the sort of hero treatment they always resisted while they were alive. Onscreen, they are ordinary people consumed with the daily struggles of earning a living and raising a family. They see their love as a sustaining bond, but never as a political statement or choice.

“It just seemed absurd to have any other approach,” Nichols says. “If you have access to what these people look like and how they behave, why would you change that? Everything I wanted out of this story was already contained within these people. I just wanted to do right by them. I wanted to show them in a light that was representative of who I thought they were.” Nichols’ hesitance to push symbolism or fabricate conflict means the story gets off to a slow start. The first scene, for instance, consists of only three words of dialogue. “I’m pregnant,” Ruth says. Blond, buzzed-cut, and generally taciturn, Richard slowly cracks a smile. “Good,” he answers.

Shakespeare it ain’t, but what Nichols’ characters lack in vocabulary, they make up for in emotional authenticity. As Richard, a mason, reveals his dream of building a home for their future family, and as Mildred slowly warms to the idea, the couple’s bond begins to grow on us, to the point that we’re firmly in their corner when their love becomes the object of segregationist persecution.

For those of us born in the last decades of the 20th century, it’s almost unthinkable that marriage across racial lines was still illegal in some states the year Sgt. Pepper’s dropped. But 37-year-old Nichols is under no illusions about the persistence of cultural and institutionalized racism, even up to the present day. “Racism wasn’t something I read about in books or heard stories of,” says Nichols, who grew up in Arkansas. “You’re confronted with it. And the worst instances are when you’re confronted with it in relatives. You know that it’s wrong. How do you react to it, how do you deal with it? These were all questions I had growing up.”

In this sense, Southern racism was an inevitable subject for Nichols, though he’s taken his time getting there. “I’ve made five films that technically take place in the South,” he says. “None of them until Loving have directly dealt with the subject of race. Part of that was on purpose, because I felt like the South had a lot of stories to tell, and they weren’t all just about race. But I also knew that it was a subject matter that was important, and when I found this story that had not been taught in my school, but was a foundational part of our American history, I was upset that I didn’t know more about it.”

In Mildred Loving in particular, Nichols has brought to screen a leading role still too rarely seen in film — a woman of color whose imagination and capabilities exceed the circumstances she’s born into. She juggles three small children in her D.C. living room, while on TV, across town, Martin Luther King gives his “I have a dream” speech. She’s not the sort of person who attends rallies and sit-ins, but even so, Mildred vows to pursue civil rights in her own circumstances. Negga is gifted with large, expressive eyes that can communicate much without the use of dialogue, and Nichols’ script often calls on this skill—for instance, when Richard forbids her to attend the Supreme Court hearing, and Ruth, clearly disappointed, tells her lawyer that she will stay home with her husband. If Loving has award-season hopes, they lie mostly with Negga’s warm, steady performance.

Loving has implications beyond the civil rights era, of course. As Nichols wrote the screenplay in 2012, he imagined he’d be releasing the finished film into a nationwide debate on the constitutionality of gay marriage. “I remember thinking there was some notion of, Wow, we need to get this thing made, because this decision will come down and it’ll be done,” he recalls. Thankfully, the Supreme Court beat his film to the punch, and the same freedom to marry enshrined in the 1967 Loving v. Virginia decision became precedent for the same-sex marriage decision of 2015.

It’s for the best that Nichols errs on the side of subtlety with his modern-day agenda. Loving rarely ventures inside the courtroom, and any parallels to the same-sex marriage struggle are muted. “It wasn’t the film’s job to make those connections,” Nichols says, “because that wasn’t what Richard and Mildred were dealing with. But the connections are so obvious to me, and I was hoping they’d be obvious to others.”

The film has other modern-day resonances as well. One is to the states-rights regime we still live with in Texas, wherein we enjoy fewer reproductive rights, voting rights, health care subsidies, and protections from guns in schools and public spaces than our fellow Americans in more progressive states. In the film, the Lovings’ final showdown with the law begins not with defiance or trauma, but with simple homesickness. Mildred, in particular, can’t stand raising her children in the city and longs to be back among her kin in rural Virginia. To do so, she risks arrest and, eventually, forces the hand of the Supreme Court in enacting a federal standard.

Freedom, Loving seems to say, is more than just the freedom to move somewhere more tolerant when your home state denies your fundamental rights. And loving is more than the relationship between two partners in marriage — it’s a force that binds communities and pushes us to make them fairer and more equitable, year after year, from one generation to the next.