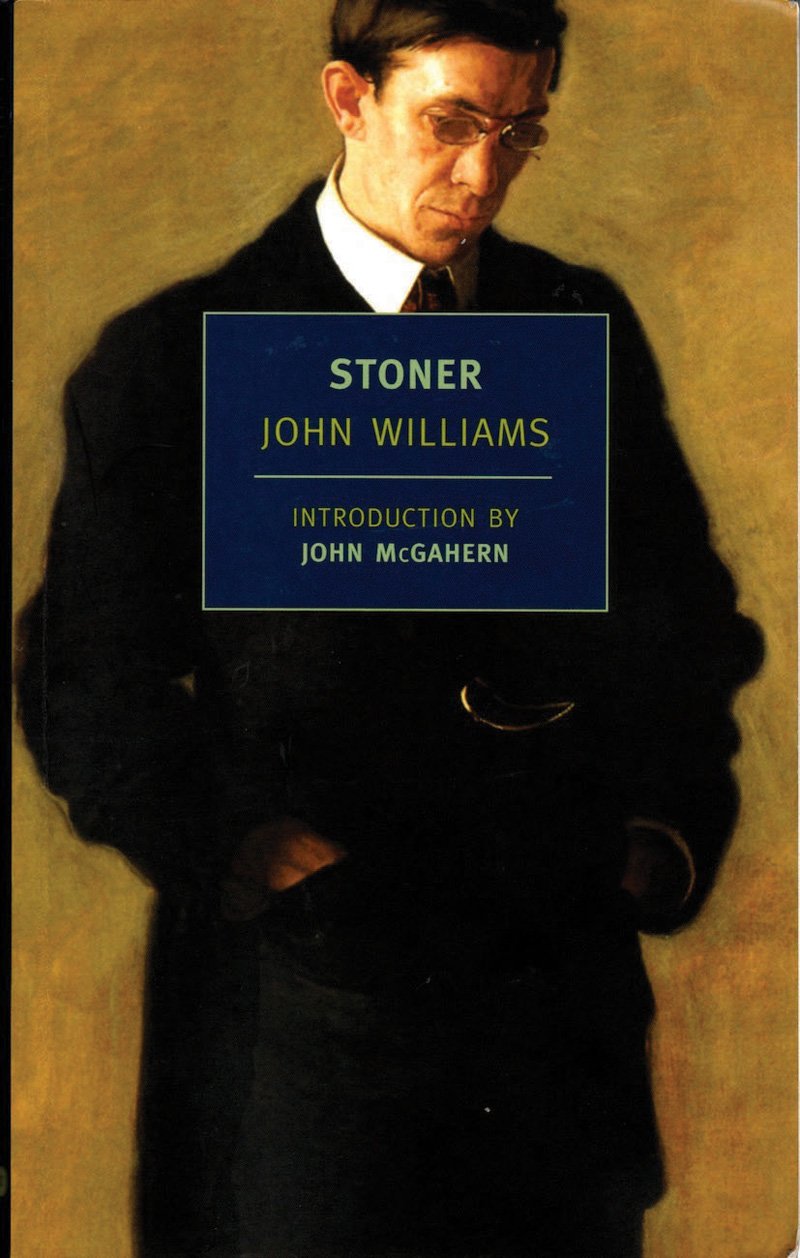

By John Williams

New York Review Books Classics

288 pages

$14.95 (New York Review Books Classics)

John Williams’ Forgotten Novel Stoner Is Worth Remembering

A version of this story ran in the October 2013 issue.

Stoner may be the greatest novel ever written by a Texas-born writer you’ve likely never heard of. Let it be said now: Stoner has nothing to do with pot. Published in 1965, the book chronicles the emotionally tumultuous life of a literature professor named William Stoner. It sold 2,000 copies and brought little public recognition to its author, John Williams (whose most famous book, Augustus, won the National Book Award for fiction in 1973). Lack of attention was fine with Williams, who lived his life much as he wrote, with a kind of measured stability and unassuming demeanor. “The plain style,” one of his friends called it.

Born in Clarksville, Williams grew up reading pulp fiction and listening to East Texas radio. He did a little writing in high school, but after flunking a literature class at a junior college in Wichita Falls he enlisted in the Army, served time in Burma, and returned to milk the GI Bill for all it was worth, eventually earning a Ph.D. in literature at the University of Missouri. In 1955 he took a job with the University of Denver’s creative writing program, which he directed until his retirement in 1985. Williams, who chain-smoked and was said to have made a kick-ass bowl of “Texas Jailhouse Chili,” died of respiratory failure in 1994.

Williams may have crafted a novel that missed the reading public’s sweet spot, but contemporary heavyweights were bowled over by his handiwork. C.P. Snow wondered, “Why isn’t this book famous?” The novelist Dan Wakefield explained in the pages of Ploughshares that Stoner “was one of the finest, most personally rewarding novels I had ever read.” When The New York Review of Books rescued Stoner by republishing it in 2006, the critic Morris Dickstein wrote in The New York Times Book Review that “it is a perfect novel.” Highbrow accolades notwithstanding, there’s a scene at the end of Stoner in which Williams writes of his protagonist, regarding the one book Stoner ever published, “It hardly mattered to him that the book was forgotten.” Williams, one imagines, foresaw the indifference that awaited.

Stoner is about the triumph of dignity in the face of heartache. As William Stoner evolves from homely farm boy to a credentialed professor (at the University of Missouri), his life becomes a passive fight to the draw against a phalanx of forces that seem maliciously preordained to derange his spirit. His wife goes more than half-loony; his daughter succumbs to alcoholism and unwanted pregnancy; the one authentically loving relationship he develops is with a graduate student who must end it so Stoner won’t get fired; Stoner’s academic battles with his nemesis, the unctuous Hollis Lomax, resemble sharks fighting for space in a bathtub; and his publishing record, as suggested, is at best thin soup. Through it all, though, Stoner sustains an understated passion. “He was,” Williams writes, “open to the world through which for a moment he walked, and he found some joy in it.”

The manner by which Williams imbues Stoner with the character required to mine joy from the wasteland of his life is what makes the novel soar. We come to admire Stoner not so much for what he says or does—he’s a reticent man who, with one heroic exception, eschews big gestures and grand statements—but through the descriptions Williams provides about an indelible aspect of his character, one that transforms an otherwise melancholy novel into the most unlikely font of inspiration. Stoner, without guile or sentimentality, lives through books. Through literature, he abides.

Bookish introspection provides Stoner a rare sort of emotional equanimity, one that comprises the emotional ballast essential to surviving the turbulence of his life. After enduring the humiliation of his first literature class, Stoner the student visits the university library, where he “wandered through the stacks, among the thousands of books, inhaling the musty odor of leather, cloth, and drying page as if it were an exotic incense.” As Stoner’s intellect matures, he feels “the urgency of study,” a feeling that leaves him lamenting “all he had not read.” When his marriage turns loveless, Stoner experiences “a weary sadness” but carries on teaching “with an intensity and ferocity that awed some of the newer members of the department.” And when his subsequent affair heats up, his lover captures Stoner’s sentiment exactly when she says, “Lust and learning … That’s really all there is, isn’t it?”

As a professor who spends considerable time trying to convince students that life’s deepest pleasures can, with a little work, be found between the covers of books, I found Stoner’s integration of literature and life to be revelatory. This is a novel that will take you back to that magical moment when you first got lost in a serious piece of literature and realized, as Stoner himself finally does, “a kind of purity that was entire.”