The Struggle to Fulfill Juneteenth’s Promise and Reckon with Its History

Sam Collins, better known as Professor Juneteenth, says his work to educate Americans about the holiday’s legacy is unfinished.

Around Galveston, Sam Collins III is better known as Professor Juneteenth.

For the past 20 years, Collins, 53, has devoted his life to educating the public about Juneteenth—the commemoration of June 19, 1865, when Union General Gordon Granger and his troops landed on the island. More than two years after the Emancipation Proclamation, Texas was then the last bastion of legal slavery. Granger read the orders freeing 250,000 enslaved Texans across Galveston, before traveling inland to proclaim freedom and the promise of “absolute equality”at plantations across Texas.

Today, Galveston is an open classroom for Juneteenth’s legacy, largely due to Collins’ efforts. He’s organized community members to get Juneteenth-related historical markers, murals, statutes, and public exhibits established. Collins worked together with Fort Worth’s Opal Lee to make Juneteenth a federal holiday in 2021. But he says that his work, as well as the promise of Juneteenth, is unfinished. He’s now trying to expand the story of Juneteenth’s legacy and bring it back home to Galveston with plans for an International Museum of Juneteenth in the port city. (A museum is also in the works up in Cowtown.)

“The Juneteenth story is much more than one day, or one city. But this is where it started,” Collins said.

I had the opportunity to join Collins as he hosted Miss Juneteenth USA, Sunshine Higgins, and Miss Juneteenth Texas, Madison Swain, on his “Freedom Walk Tour,” which highlights the sites where the orders of freedom were read. Higgins and Swain are both college students who won scholarships through Juneteenth-themed pageant programs. As we walked around Galveston, I learned about Collins’ own history, work, and plans to continue promoting Juneteenth’s legacy in his hometown.

-

We started at the Nia Cultural Center, a gallery dedicated to promoting the history and legacy of Juneteenth as well as the work of Black artists. Collins explained its exhibits to Higgins and Swain. Credit: Josephine Lee -

In front of the Middle Passage historical marker on the Galveston Historic Seaport building, Collins explained the role that Galveston played in the slave trade. “For a period of time, along the Middle Passage routes, 90 percent of the transatlantic slave trade went to South America and the Caribbean islands. Only 6 percent came into what is now considered the United States. Of that, 80 percent came through Galveston, and from there, enslaved people would walk into Texas or were brought over by wagons.” Credit: Josephine Lee -

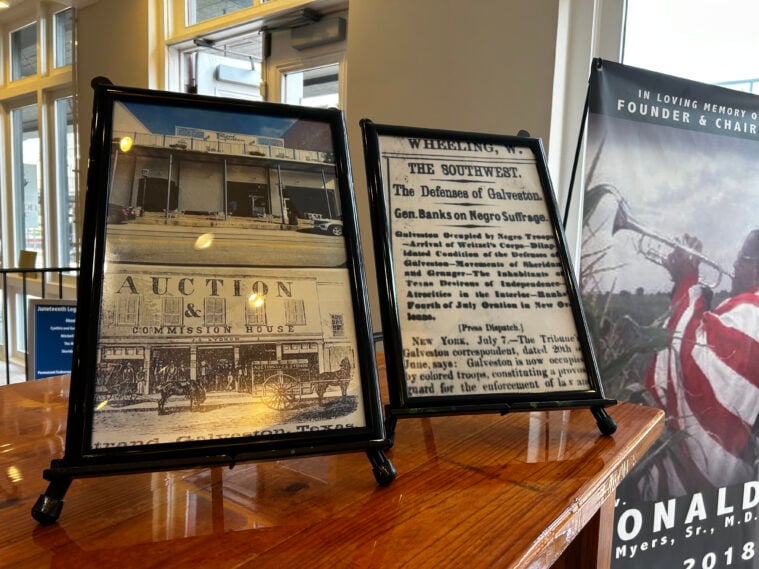

Inside the Nia Cultural Center, photos display the Roof Garden wedding venue across the street, a space that one of Galveston’s many cotton commission and slave auction houses once occupied. Credit: Josephine Lee -

“This is an example of a sale that was made in 1837 of 36 enslaved people to the Bynum Plantation. David and Robert Mills were the largest enslavers in the state of Texas. The reason I am bringing it up is to show that children younger than 10 years old stayed with their mother. At ten, they could be sold individually,” Collins said. Credit: Josephine Lee -

At the Reedy Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church, Collins, Swain, and Higgins stand with Diane Henderson-Moore, the church’s steward. Henderson said the church’s congregation was founded in 1848 by enslaved African Americans who first met in an open outdoor space until a building was constructed there in 1863. Following June 19, 1865, the church ran a school for the Black community, and in 1866 the church was organized as Texas’s first African Methodist Episcopal congregation. Credit: Josephine Lee -

A statue of General Gordon Granger stands in front of Ashton Villa where his five orders were also read to citizens on June 19, 1865. The third of these orders freed enslaved Texans. Credit: Josephine Lee -

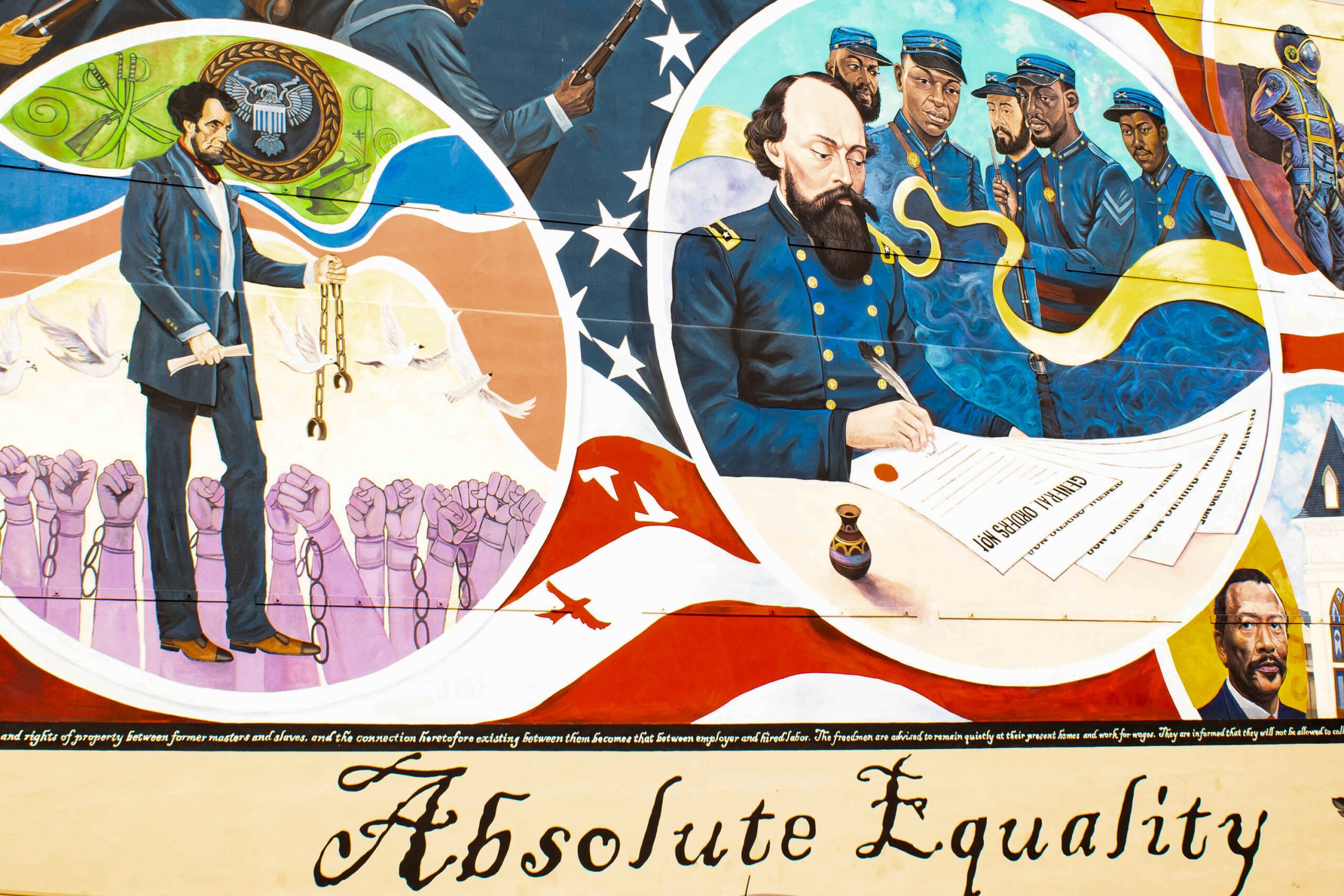

With the Juneteenth Legacy Project, Collins spearheaded the creation of the “Absolute Equality” mural on the east side of the Nia Cultural Center. The mural was painted by artists Samson Adenugba, Cherry Meekins, Joshua Bennett, Reginald Adams, KaDavien Baylor, and Dantrel Boone. Visitors can use the Uncover Everything App to see videos about the depicted subjects. Credit: Josephine Lee -

At the Galveston Historical Foundation’s African American Heritage Committee’s Juneteenth Exhibit, “And Still We Rise,” Collins points to sites along his Freedom Walk Tour. In addition to oral histories, the exhibit features interactive visuals about Juneteenth. Credit: Josephine Lee

Collins wears many hats around Galveston. He’s a father of four, an associate minister at his church, and a financial consultant. But he’s best known as a public historian, who regularly lectures on Black history and also sits on the board of the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

His own family’s history in Texas dates back seven generations to 1837, when his oldest documented ancestor Joseph Thompson was brought to Brazoria County as an enslaved child. Other family members hailed from San Felipe and Sealy. Like many other Black families who fled to the bigger cities of Houston and Galveston in the decades after 1865, Collins’ family sought better opportunities on the island in 1925. But every Juneteenth, they made their way back home to celebrate the holiday with extended family members.

“It was important for people to make the connection from the cities to where their families had roots. Most enslaved people had worked in the southeast region of Texas, close to the coast. So people would go back home … and celebrate it with their families. It’s been a tradition since 1865,” Collins said.

As a child, Collins attended parades and festivals in Galveston and nearby in his smaller hometown of Hitchcock. Celebrations were about family and community, but it wasn’t until he was older that Collins started learning more about the holiday’s history. In 2006, he gathered what he found and hosted his own Juneteenth celebration at the Stringfellow estate in Hitchcock, a former plantation that Collins had purchased and repurposed as a family home and space to present Black history. Six-hundred people attended that celebration.

That same year, Ronald Meyers, a Mississippi doctor who had since 1999 been championing a federal Juneteenth holiday, reached out to Collins for help. Through the National Juneteenth Observance Foundation, Meyers worked with Opal Lee, who became the foremost representative of the national campaign, and Collins. Meyers died in 2018, before he saw his work realized. “He drove all across the country and sacrificed a lot of his personal resources, but his role in the movement has been forgotten,” Collins said.

It’s why Collins makes sure to mention Meyers and others who have fought for Juneteenth recognition. As early as 1879, Robert Evans, a Black state legislator from Navasota tried to get Juneteenth recognized as a state holiday. But that was two years after the Compromise of 1877 ended Reconstruction and, along with it, the promises to protect the rights of Black Americans. It wouldn’t be until about a hundred years later, following the civil rights movement, that calls to fulfill the promise of “absolute equality” would be collectively renewed. Juneteenth finally became a Texas holiday in 1980.

Despite the work of Meyers, Lee, and Collins, among others, it would be the 2020 mass protests against racist police brutality that spread following the murder of George Floyd that would push the federal government to recognize Juneteenth. “That started a social movement, an uprising and awakening of consciousness. The National Juneteenth Observance Foundation had been trying to get recognition for 26 years, but no one was paying attention, until after what happened to George Floyd,” Collins said. After more than 150 years, President Joe Biden signed the Juneteenth bill in June 2021.

Collins’ work didn’t end there. Later that year, he worked with the Juneteenth Legacy Project and artists to create a public art mural at the site of where Granger first read his orders. The goal was to expand the narrative of Juneteenth to include a continuous struggle for “the absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves,” as proclaimed by Granger’s order. From Harriet Tubman to the Black troops who enforced the order throughout Texas to those who fought for federal recognition of Juneteenth, Collins said Black Americans are “still traveling that road.”

On the stoop of Reedy Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church, Collins told me that he’s now trying to bring the story of Juneteenth back to Galveston. It makes sense as the port of Galveston served as the beginning and end of slavery: the site where enslaved people once entered into the country to be sold in the city’s auction’s houses, where cotton was traded and shipped out, and where the last stand to hold on to this brutal system took place before the final group of African Americans were freed. It’s a history that some Galveston officials have been hesitant to reckon with, according to Collins.

“Some don’t want to paint Galveston in a negative light centered around slavery, since it’s seen as a tropical vacation spot,” Collins said. “‘Slavery wasn’t that bad, we always got along, there were never any racial problems’—that’s another version of that history seen through the eyes of a privileged few.”

But Collins believes Galveston still has a greater role to play in presenting Juneteenth’s legacy and the city’s history as it relates to the country’s. He’s been organizing supporters for a Galveston International Juneteenth Museum and has already engaged the Prairie View architectural school to come up with designs. Those designs were then shared and voted on by community members. Collins said that while they have the concept, they still don’t have a location. The selected design now hangs in the Nia Cultural Center, near the site where Granger first read the orders to free enslaved people in Texas.

Quoting Frederick Douglass, Collins said that it’s an ongoing struggle to achieve “absolute equality,” just as it’s an ongoing struggle for Americans to reckon with their past. “Those who profess to favor freedom and yet depreciate agitation, are people who want crops without plowing the ground,” Douglass said at a speech in Canandaigua, New York, in 1857. “They want rain without thunder and lightning; they want the ocean without the roar of its many waters.”