When Fort Worth activist Opal Lee was invited in 2021 to stand alongside President Joe Biden as he signed the bill making Juneteenth a federal holiday, “I could’ve done a holy dance,” the 97-year-old told the Texas Observer recently. “But the kids said they didn’t want me twerking.”

Dancing—and twerking—aside, Lee is clearly used to ambitious projects. She’s often referred to as the grandmother of Juneteenth, mostly because of her 1,400-mile walk, Fort Worth to Washington, D.C., September 2016 to January 2017, seeking recognition for the day that has come to represent freedom for American Blacks. Although the Emancipation Proclamation took effect in 1863, slaves couldn’t be freed where the countryside was still under Confederate control. That ended in Texas on June 19, 1865, when Union troops arrived in Galveston and brought the news.

The latest project of Lee and her allies, to create a museum in Fort Worth honoring Juneteenth, is turning out to be equally ambitious. What began as a modest collection in a small house in the neighborhood where Lee grew up has become a key part of an effort to revitalize Fort Worth’s Historic Southside neighborhood. The most recent and much grander incarnation of the museum is due to open in 2025.

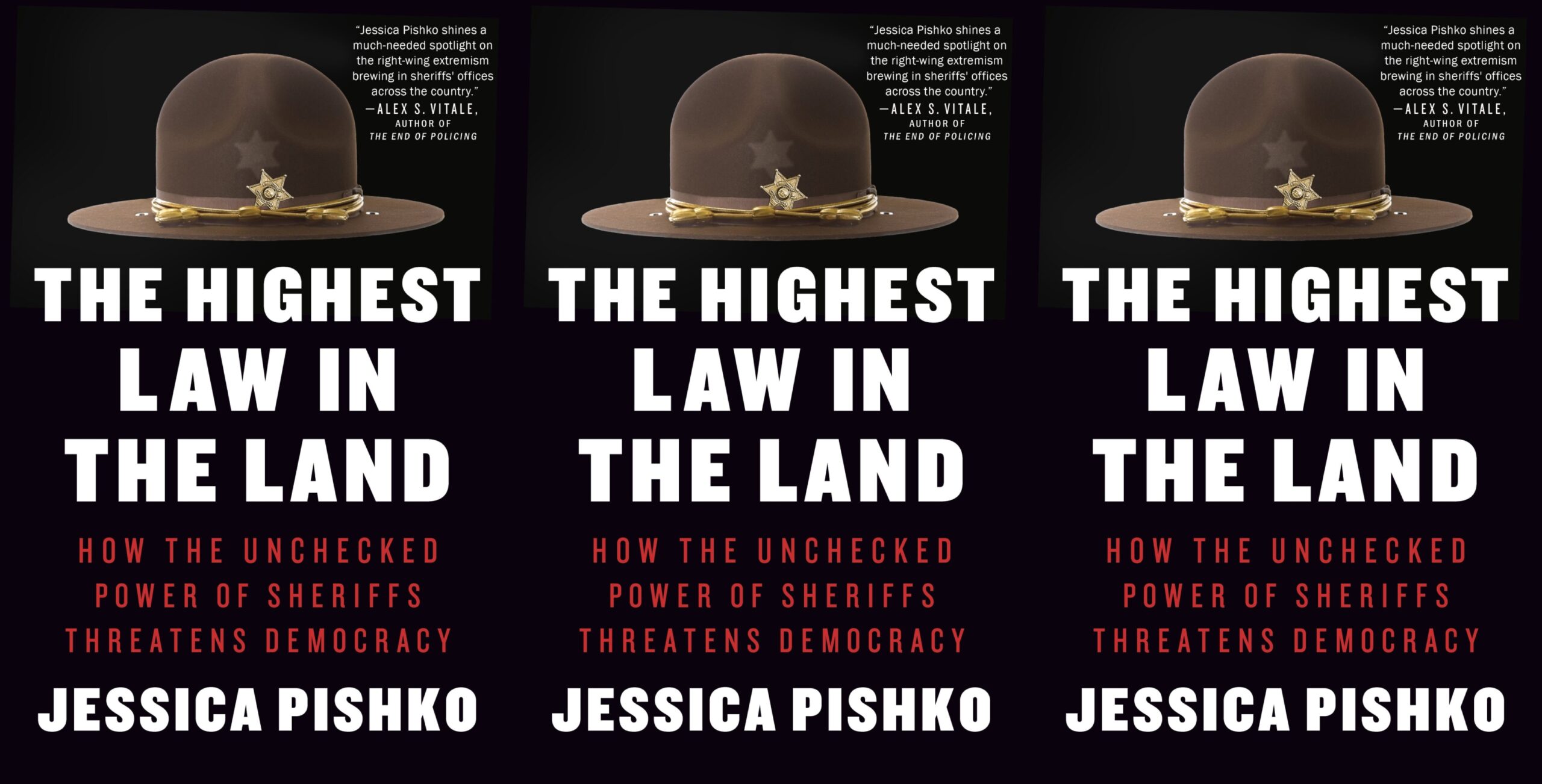

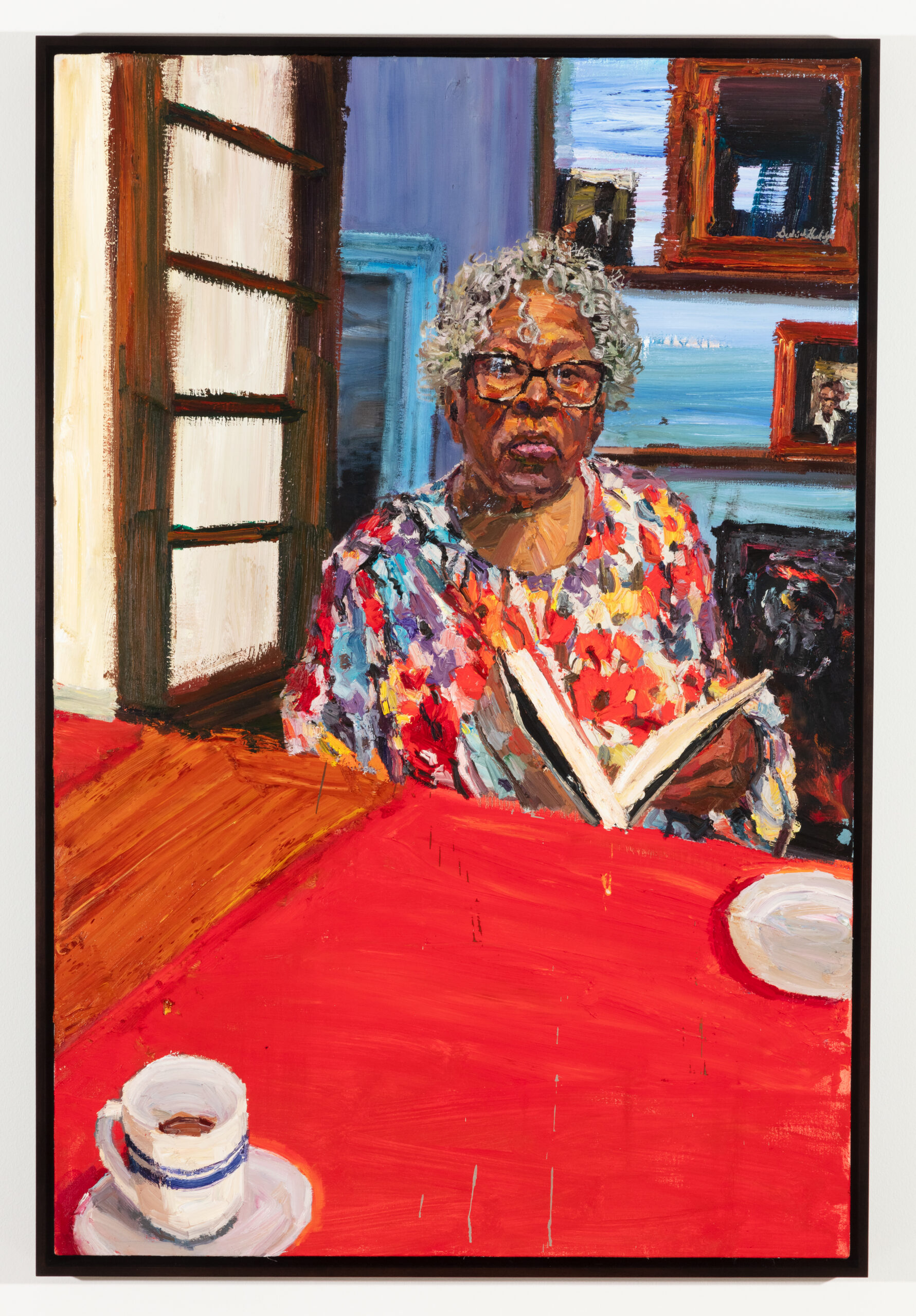

Along the way, the honors paid to Lee—a Nobel Peace Prize nomination, a painting of Lee for the National Portrait Gallery, and the Emmy Award-winning documentary Opal’s Walk for Freedom (2022)—have helped bring attention to that neighborhood, just as they did to the Juneteenth campaign. But tragedy and poverty have held hands there for a long time, and revitalization efforts sometimes find tough sledding.

Lee’s roots run deep into the soil of the Southside and into personal memories of another June 19. On that day in 1939, a mob of racists—about 500 people, according to the Fort Worth Star-Telegram—raided the house there that Lee, her parents, and two brothers, had recently moved into. The family promptly moved out.

The raid was traumatic. Lee told the Star-Telegram in 2003 that afterward her family was “homeless and then living in houses so ramshackle they were impossible to keep clean.” The experience led her to become first an advocate for affordable housing and later an activist regarding homelessness, hunger, and Juneteenth.

Eighty years after the raid, another violent incident a few blocks away would inspire a new generation of Southside activists.

Lee, a retired elementary school teacher and counselor in the Fort Worth school district, also spearheaded the rebuilding of the Metroplex Food Bank (now the Community Food Bank), founded the urban Opal’s Farm, and served on numerous local boards, including the Tarrant Black Historical and Genealogical Society.

Through all that time, she worked to draw attention to Juneteenth. “She was always teaching about Juneteenth” in middle school, said Sedrick Huckaby, the Fort Worth artist who painted Lee for the National Portrait Gallery. “She was always teaching about our heritage and about taking pride in who you are.” Allies like the late Rev. Dr. Ron Myers, a Mississippi doctor and minister, lobbied legislatures across the country and in 1997 helped pass a congressional joint resolution recognizing the holiday. Lee worked on building local support.

In 2014, on the 150th anniversary of Juneteenth, she asked friends and family to donate to a celebration of that, in lieu of buying presents on her birthday. A story in Fort Worth Weekly called her “part grandma, part General Patton” in leading the effort. Two years later, she was putting on her walking shoes for her own personal march on Washington. “If a lady in tennis shoes walked to Washington, D.C, maybe people would pay attention,” she said in her deep, raspy voice, recalling her motivations for the trek. It took another four years after her walk, but the national holiday happened.

Juneteenth has been celebrated by Black Americans for more than 100 years, including in Fort Worth. Texas was the first to designate it a state holiday, in 1980. Since 2020, 26 states, propelled by the murders of Black citizens George Floyd and Breonna Taylor at the hands of police, have followed Texas’ lead, according to the Pew Research Center.

In Fort Worth, Lee and volunteer Don Williams had been working for years to gather artifacts related to local Black history and Juneteenth, including paintings by local Black artist Manet Harrison Fowler, scrapbooks chronicling local Juneteenth celebrations, and memorabilia from the locally filmed movie Miss Juneteenth. Lee inherited a house from her late husband Dale, a retired school district principal, and turned it into the first version of the Juneteenth museum. It housed the growing collection and hosted multiple Juneteenth events and, at one point, computer classes.

While the collection grew, the building, run by volunteers, was deteriorating. Like most public places, it closed in 2020 as COVID-19 spread. After the pandemic, it did not reopen, and the collection was moved out. Then early on the morning of January 11, 2023, it caught on fire. The remains were demolished to make way for the new museum.

Around 2019, Lee, granddaughter Dione Sims, and former Fort Worth Chamber of Commerce executive Jarred Howard had started talking about the possibility of a new Juneteenth Museum. They began buying land around the site of the old house. Howard long had a vision to help his old stomping grounds and wanted to both commemorate the holiday and spur economic development. Well acquainted with developers and architects from his Chamber days, he solicited requests for proposals for a building that could meet those goals. First, local architect Paul Dennehy designed a five-story building with a gallery, event space, and residences. In early 2020 it was pitched to neighborhood association leaders. Too tall, they said, and out of step with the neighborhood. In 2021, local architects Bennett Partners produced a plan for a playful mixed-use campus, estimated to cost about $30 million to build.

In 2022, a new plan, bigger in scope than Lee could have imagined two decades ago, was unveiled. The current proposal is for a 5-acre complex housing a National Juneteenth Museum, with a theater, restaurant, art galleries, and a “business incubator” space to spur Southside entrepreneurship, designed by the internationally renowned architecture firm Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG). The price tag is an estimated $70 million. So far, the nonprofit National Juneteenth Museum, formed in 2020, has raised about $30 million of that, mostly from major donors and foundations, Lee said.

Douglass Alligood, a partner at BIG and the chief architect of the currently planned museum, got an earful during his field work on the project, including from Lee’s friends and supporters. In multiple visits, he met with Lee as well as neighborhood leaders. The conclusion: The museum had to represent the community and not be divorced from it.

“We were inspired by the neighborhood typology—the homes that feature historic gabled silhouettes and protruding porches, also known in context as a ‘shotgun’ house.”

“We were inspired by the neighborhood typology—the homes that feature historic gabled silhouettes and protruding porches, also known in context as a ‘shotgun’ house,” he said. “Neighborhood groups and community members found that, together, the BIG and KAI Enterprises [the local architecture firm] design teams demonstrate a deep understanding of the Juneteenth story and commitment to work with the local community to celebrate the holiday’s history and local culture of the Historic Southside.”

Eleven rectangular glass-clad building segments, with peaks and valleys of varying heights, will create a star-shaped courtyard in the middle. “The ‘new star,’ the nova star represents a new chapter for the African-Americans looking ahead towards a more just future,” Alligood said.

Fine, locals said, but what people there really need is a grocery store.

It was a cold morning in early October, and Patrice Jones needed help unloading herbs. She was in the courtyard of Connex, a new three-story business and retail complex about two blocks from the planned site of the museum. Jones and a group of volunteers, mostly in their 20s and 30s, from Southside Community Gardens, are planting their 79th and 80th backyard vegetable gardens in the neighborhood, she said proudly. It’s pick-up day for those who’ve already established gardens.

The initiative is part of the larger By Any Means 104 effort, named for the 76104 zip code, and co-founded by Jones in 2020. The group’s focus on local issues includes addressing the lack of fresh food in the area instead of waiting for a grocery store. Jones, a feisty advocate and former claims adjuster, has run it full time since 2021. If the city can’t get them a grocery store, she said, they’ll teach residents to grow their own food.

The Juneteenth Museum is important, Jones said, between handing out herbs and greeting volunteers. But in her circles, she said, people also ask, “Can we get a health clinic? Can we get a pharmacy?” And of course, “Can we get a grocery store?”

According to a 2018 University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center report, the 76104 zip code has the lowest life expectancy rate in Texas and a high maternal mortality rate. It’s also a victim of what Jones calls “food apartheid,” a term she prefers to “food desert,” an indicator of an area with little access to fresh foods. Desert implies it’s natural; apartheid, she said, is an intentional act. She blames city government and its white-dominated culture.

Can we get a health clinic? Can we get a pharmacy? Can we get a grocery store?

But hunger is not a sufficient reason for a grocery chain to decide where to open a store, even if it could be part of a historical complex.

Grocery store owners “use different metrics,” including population density, said Stacy Marshall, president of Southeast Fort Worth, Inc., an economic development group. “We can’t yet make a compelling case.” The area needs more housing, he said. “Build density—rooftops—and grocery stores come.”

Marshall is a force in bringing new development to the southeast part of the city, a large historically and ethnically diverse area that includes the Historic Southside.

Since he took the job a decade ago, “development has gone gangbusters,” he said. But development has also brought gentrification: “It’s so expensive to purchase dirt here and get a single-family home,” he said. One Dallas real estate firm put together a $70 million deal for a mixed-use development in the area, but it has stalled.

The Juneteenth museum site is within the Evans-Rosedale urban village, a city designation focused on bringing investment to the area. It’s seeing an uptick in interest from developers, but nowhere near what’s been promised by local officials.

“There have been attempts in the past. There’s the Evans Avenue Plaza, but most people don’t know about it,” said Bob Ray Sanders, communications director for the Fort Worth Black Chamber of Commerce. The plaza, also part of the Evans-Rosedale village, is meant to be a community gathering space and includes a new library. About a mile away is the Hazel Harvey Peace Center for Neighborhoods, which houses numerous city offices.

Many of the neighborhood’s nagging problems date to the mid-20th century, when integration meant, ironically, the loss of many black-owned businesses, while highway construction—as it did in many American cities—cut off Fort Worth’s Black community from downtown and wealthier neighborhoods. “By doing that, people on the Westside [turned] a blind eye to people on the Eastside,” Sanders said.

Housing construction seems to be picking up, mostly on an infill basis. But while developers are buying homes, Marshall said, they are mostly sitting on them and waiting until they can get higher prices.

Longtime assistant city manager Fernando Costa said development work in historic urban districts presents more challenges than creating new neighborhoods from pastureland. Beyond the physical complications of older infrastructure, historic preservation concerns and, often, environmental problems left over from earlier development, Costa said, such projects “require getting existing neighborhood involvement.”

There’s also the issue of crime. According to the Fort Worth Police Department, nearly 560 crimes were reported in the 76104 zip code between mid-May and late November 2023. Assault, larceny, drug and alcohol violations, and vehicle break-ins made up more than three-quarters of the reports. That’s compared to 165 in the same time period in the mostly-white, wealthy 76109 zip code in West Fort Worth.

In the early morning of October 12, 2019, white police officer Aaron Dean, responding to a welfare check at the house, killed 28-year Black woman Atatiana Jefferson, who was playing video games with her nephew. Dean was later found guilty of manslaughter and sentenced to 11 years in prison.

Jefferson’s murder lit a fire under a younger generation of activists who aren’t waiting for change, such as Jones, who also worked to get police accountability in response to the murder, and Angela Mack, whose doctoral thesis is about Jefferson and the neighborhood.

“I’m a good, ol’ fashioned Funkytown Black nerd,” said Mack, an instructor in the comparative race and ethnic studies department at Texas Christian University, where she received her doctorate in English rhetoric.

After Jefferson’s murder, Mack changed her thesis topic to address that tragedy. She saw that, between her mother and the national media, two different stories were being told.

“When we’re thinking about the Southside, we think about Fairmount and the Medical District in terms of revitalization. But when you cross the highway, you’re in an area with crime and poverty,” she said, drinking a latte at Black Coffee, one of the few coffee shops in the area. “When people [look] at the community, people are looking at what’s not here. It’s a deficit model of communication instead of seeing the good that’s here.

“I’m not anti-development,” she said, but economic development shouldn’t be the museum’s purpose.

“When you’re building something, it should not be [a question of] how many people we employ, but how does it help define the Southside? The development will come. I’m concerned about who controls the narrative,” she said. “The main focus should be how does this speak about our history and heritage.”

Jones also worries that history will be lost. She’s afraid that rising property values will push out poor people.

Sims has heard those concerns before. Property taxes go up with any new development, she said. And everyone’s going to complain, even if they want change.

When the museum opens in 2025, Lee just wants to make sure she’s there to see it.

“I’m looking forward to it,” she said. She’d be 99. “I hope I’m still here.”