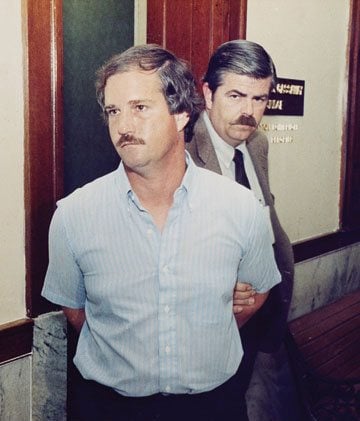

Ed Graf Trial Ends in Guilty Plea

Update: Ed Graf struck a plea deal on Tuesday afternoon, taking the verdict out of the jury’s hands while it was still deliberating. Graf pleaded guilty to two counts of murder and received a 60-year sentence.

It was stunning to hear Graf admit guilt. He did so to maintain his eligibility for parole. Under the plea deal, Graf will be credited for the 25 years he served in prison, including his time for good behavior.

That means Graf will likely be paroled from prison in just a few months under a mandatory release policy that was in place at the time of his offense. Graf feared a guilty verdict that might have denied him a chance for parole or a hung jury that would leave him in county jail for perhaps a year or more awaiting a new trial. Instead, he agreed to plead guilty knowing he would be paroled in a few months. I’ll have a full story on the bizarre conclusion to the Graf case posted soon.

Original post: Ed Graf’s fate now lies with a Waco jury.

Testimony in Graf’s controversial re-trial concluded on Friday, and attorneys presented their closing arguments this morning. The six men and six women of the jury will now decide if they believe that Graf murdered his 8- and 9-year-old stepsons by starting a 1986 fire in a shed behind his house; or if Graf was wrongly convicted and spent decades in prison for what was actually an accidental fire.

Graf was originally convicted in 1988 and spent 25 years in prison. His conviction was overturned last year after advancements in the field of fire science disproved the physical evidence that convicted him. Yet McLennan County prosecutors chose to re-try him. (You can read the Observer’s 2009 investigation of Graf’s case here, our piece about the flaws in the evidence here, and my dispatches from earlier in the trial here and here.) Graf’s is the first case to reach re-trial since Texas began reviewing flawed arson cases following the Cameron Todd Willingham controversy.

As I noted at the beginning of the trial, prosecutors faced a difficult mission, trying to convict Graf with largely circumstantial evidence. Prosecutors couldn’t use any of the discredited arson evidence from the original trial. In fact, most of the physical evidence—analyzed using modern techniques and a modern understanding of fire—points to an accidental fire.

Science may not have been on their side, but prosecutors put on quite a case. They dredged up much of the circumstantial evidence from the first trial, the most damaging of which was the $50,000 insurance policy Graf took out on the boys the month before the fire, and a comment Graf allegedly made to a co-worker that his marriage would be better without the boys. The defense countered that the insurance coverage was a universal policy that’s commonly used as a good investment for kids and that Graf’s remark was simply an innocent complaint about his home life.

But the most stunning testimony came from a jailhouse informant.

Fernando Herrera, an inmate at the McLennan County jail who said he got to know Graf over the past few months, was likely the most controversial of the more than 30 prosecution witnesses. Herrera testified, as Tommy Witherspoon, the Waco Tribune-Herald’s long-time courthouse correspondent reported, that Graf confessed the crime to him in detail. He testified that Graf admitted to burning the children alive for the insurance money. Graf admitted, according to Herrera, that he had been struggling financially. Graf’s supposed confession went into surprising detail, including how he used ropes to tie the boys up and how he requested one casket at the funeral. He also supposedly told Herrera in jail that he had locked the boys in the shed, then opened the door just before neighbors saw what he was doing.

(Whether the door was open or closed is a key point. The door only locked from the outside, and Graf was the only adult in the house. So if the door was closed and locked, that would point toward Graf’s guilt. But witness testimony is mixed—some firefighters swear the door was closed and neighbors swear the door was open. The fire scientists say the door had to be open or the fire would have died out from lack of oxygen.)

Herrera’s supposed confession just happens to match much of the prosecution’s theory of the case. In Herrera’s version, Graf locked the boys in the shed, then opened the door just in time to supply the fire with needed oxygen.

Defense lawyers sought to discredit Herrera, pointing out that he has at least six known aliases and more than a dozen convictions. They also noted that Herrera had asked for preferential treatment in jail multiple times before contacting prosecutors about the Graf case. Still, Herrera claimed prosecutors weren’t giving him anything in exchange for his testimony.

Defense attorneys also noted how unbelievable it seems that Graf would spend 25 years in prison, then, after his conviction was overturned, confess to a random jail inmate just before his retrial. Moreover, jailhouse informants don’t have the best track record, as the Innocence Project reports.

The defense team built its case on the scientific evidence. Doug Carpenter, a nationally renowned fire expert, was the key witness. He testified that the high carbon monoxide levels in the boys’ bodies point to an accidental fire (gasoline/arson fires typically result in low carbon monoxide levels. More on that here.) The defense also offered evidence that the boys had played with matches on several occasions and theorized that the boys had started the accidental fire themselves.

In his closing argument, prosecutor Michael Jarrett told the jury to ignore the scientific testimony and to go with their “heart,” as Witherspoon reported on Twitter.

That’s the essence of the case: Will the jury go with their heads or their hearts, with the scientific evidence or with their suspicions?

In many ways, the prosecutors’ case felt very familiar. They vilified the defendant, emphasized circumstantial evidence and offered fantastic testimony from a jailhouse snitch. Quite a few Texans have been wrongly convicted with this formula.

The difference this time is that the defense had modern fire science on its side. The jury will decide if the scientific testimony is enough to outweigh the considerable circumstantial evidence and the informant.

In that sense, the Graf case feels very much like a contrast between the old method that Texas prosecutors have used to convict people for years and the new approach to criminal cases based on more reliable, scientific evidence.

For Graf, 62, the stakes are high. If he’s found not guilty, he’ll be free for the first time in 26 years. If he’s convicted of capital murder, he may well die in prison.