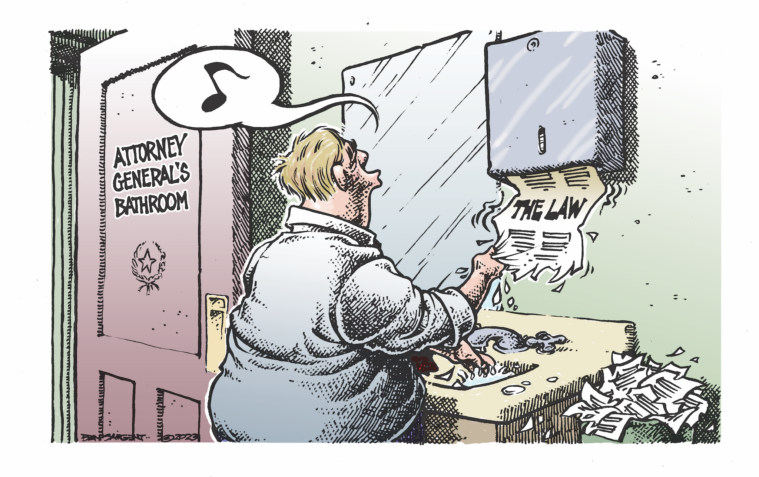

Ken Paxton Repeatedly Refused to Defend State Agencies in Court

Why won't the Attorney General do his job?

ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for Dispatches, a newsletter that spotlights wrongdoing around the country, to receive our stories in your inbox every week.

This article is co-published with the Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan local newsroom that informs and engages with Texans. Sign up for The Brief Weekly to get up to speed on their essential coverage of Texas issues.

When Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton held a news conference in May decrying state lawmakers’ anticipated vote to impeach him, he framed the decision as not only a threat to his political career but as one that endangered the slew of lawsuits he’d filed against the Biden administration.

Paxton, who has since been suspended from office, faces an impeachment trial that starts today. He has long positioned himself as one of the country’s strongest conservative attorneys general, relentlessly pursuing nearly 50 lawsuits against the federal government on issues that include immigration, health care and the environment. Such messaging raised Paxton’s national profile, appealed to his base of conservative supporters and helped him tamp down political pushback stemming from allegations of wrongdoing that have dogged his eight-year tenure.

But as Paxton has aggressively pursued such lawsuits, he has repeatedly declined to do a critical but less glamorous part of his job: represent state agencies in court.

Despite his role as Texas’ lead attorney, Paxton has denied representation to state agencies at least 75 times in the past two years, according to records obtained by ProPublica and The Texas Tribune. The denials forced some of those agencies to assume additional, unanticipated costs as they scrambled to secure legal assistance.

“Every time he backs out of one of these cases – and an agency, a university has to get outside counsel, if they get the funding approved – that’s costing the taxpayers a lot of extra money, because that’s one of the principal reasons the AG’s office exists, is to provide these basic legal services, basic legal defense,” said Chris Toth, former executive director of the National Association of Attorneys General.

Over the years, some of Paxton’s representation denials have become public. Among those is his longtime refusal to defend the state Ethics Commission against lawsuits filed by the now-disbanded Empower Texans, a political action committee, and the PAC’s then-head Michael Quinn Sullivan. Empower Texans contributed hundreds of thousands of dollars to his campaign and loaned him $1 million, according to campaign finance reports. Another has been his choice not to represent the State Commission on Judicial Conduct after it issued a public warning to a justice of the peace who refused to perform same-sex marriages despite a U.S. Supreme Court decision that legalized the unions.

But the scope of the denials has not been fully known. Neither have details of other times he has said no to state agencies seeking representation.

In one such instance, Paxton declined to represent the University of Houston–Clear Lake after students filed a lawsuit alleging the university wouldn’t recognize their organization because of the group’s requirement that its officers be Christian. Until then, the attorney general’s office had never before declined to represent the university in a case, said university spokesperson Chris Stipes.

In another instance, Paxton’s office not only held off on a decision to represent the University of Texas System in an affirmative action case, but also withheld a determination on whether the university could hire outside legal counsel, forcing multiple delays. That choice stands in contrast to Republican Gov. Greg Abbott’s decision to represent the University of Texas at Austin in a similar case 15 years earlier when he was the state’s attorney general.

Texas lawmakers in 2021 required the attorney general’s office to begin reporting each time it declined to represent a state agency. It’s unclear what prompted the mandate.

ProPublica and the Tribune obtained records documenting dozens of denials through a Public Information Act request, but the vast majority do not include a clear reason for the decisions. The attorney general’s office declined to provide specifics about its communications with state agencies, including those that occurred before the reporting requirement went into effect, citing attorney-client privilege. The office also did not respond to a question about whether the agency tracked these denials prior to 2021.

Lawmakers took additional action this year, requiring the attorney general to start giving reasons for the denials beginning Sept. 1.

Paxton’s office has claimed that the bulk of those denials were because agencies preferred to hire their own attorneys or because the office was statutorily prevented from representing them. Other requests, Paxton has said, were turned down because they would have required his office to take a position opposite of what it had previously argued or because he believed they would run contrary to the state’s constitution.

An office spokesperson said the attorney general approves the vast majority of solicitations for help, but neither the office nor Paxton responded to requests for interviews or to detailed questions about specific denials.

Such transparency is necessary, according to former attorneys general and legal experts, who say that Paxton’s denials reflect a broader polarization among attorneys general across the country, threatening the claim that they represent the rule of law.

“He certainly was one of those people that was leading the way of this idea that they don’t have to enforce or defend anything they don’t like,” Toth said. “And that’s not what AGs are elected to do. And it’s not the courageous thing to do either because AGs have to do the right thing by the law, even when it’s not popular.”

In 2014, Colorado’s then-Attorney General John Suthers, a Republican, penned an opinion piece in the Washington Post that warned against such politicization of the office. In the piece, Suthers criticized three Democratic attorneys general at the time, including California’s Kamala Harris, now U.S. vice president, for refusing to defend their state’s ban on gay marriage ahead of the Supreme Court’s 2015 decision legalizing the unions. “I fear that refusing to defend unpopular or politically distasteful laws will ultimately weaken the legal and moral authority that attorneys general have earned and depend on,” he wrote.

Suthers reiterated the same concern about Paxton’s refusal to defend state agencies in an interview with ProPublica and the Tribune.

“If you decide for yourself what laws ought to be defended, what agencies ought to be defended on other than dictates of the courts, then you come across as nothing but a wholly political entity,” Suthers said. “That’s not the role that you’re supposed to play in the system. Let the legislature and the governor be political. You’re supposed to be adhering to the rule of law.”

Growing costs

During a legislative committee hearing in February, Mary González, a state representative from the El Paso area, grilled Paxton about his decisions to not represent state agencies. She and other lawmakers had just finished asking Paxton about his office’s agreement more than a week earlier to pay $3.3 million to settle a whistleblower lawsuit with former employees who had accused him of bribery and retaliation.

González, a Democrat, asked Paxton if he had made an active decision to have the attorney general’s office take on the lawsuit filed against him. She noted that Paxton’s office could have declined to represent him in court the same way it had denied representation to state agencies.

“Ultimately, the attorney general isn’t doing his job,” González said in an interview with the news organizations. “We should care if any elected official is not doing their job.”

Paxton and his staff did not directly answer González’s question but raised the various reasons the office would not take on a case, including instances when it thinks an agency’s argument violates the constitution.

“If we’re given a case that appears to us clearly to be unconstitutional, they want us to take a position against the constitution. That’s a real problem for me given my oath,” Paxton said.

Two days later, Jacqueline Habersham, executive director of the State Commission on Judicial Conduct, appeared before the same legislators to request $150,000 to help cover legal fees over the next two years. Paxton has refused to defend the commission in two ongoing lawsuits.

In late 2019, a justice of the peace in Waco, Texas, less than two hours south of Dallas, sued the judicial commission in district court after it issued her a public warning because of statements she made to the media about disagreeing with and refusing to perform same-sex marriages after they’d been legalized, casting “doubt on her capacity to act impartially.” The lawsuit argued that the commission’s public punishment of the justice of the peace constituted “a substantial burden” on her “free exercise of religion,” according to court records.

A few months later, the county judge of Jack County, northwest of Fort Worth, sued the judicial commission in federal court, arguing that he also was at risk of being sanctioned because he did not perform same-sex marriages. An attorney for the county judge declined to comment.

The cases, and the costs, are ongoing.

Even before Habersham went to lawmakers for help, the judicial commission had already spent $120,000 for outside counsel because Paxton had declined to provide representation. She said the small agency had previously not budgeted for such expenses. With the commission having no way to know if the attorney general will deny legal help again, “we’re just hoping that no other lawsuits are filed against us, where the AG will also decline (to represent us) again,” Habersham said in an interview with ProPublica and the Tribune.

In 2015, after the U.S. Supreme Court legalized gay marriage, Paxton issued an opinion that said judges should not have to perform these ceremonies if they have religious objections. Asked in 2020 about not representing the commission, an attorney general spokesman told the Houston Chronicle, “We believe judges retain their right to religious liberty when they take the bench.”

The statement and Paxton’s decision against defending the judicial commission “certainly has the appearance that he’s refusing to do it because he disagrees with the Supreme Court decision, and therefore he’s making a political decision and not a legal decision,” said Suthers, the former Colorado attorney general.

The plaintiffs in both lawsuits filed against the commission have at some point been represented by First Liberty Institute, a Plano-based conservative Christian law firm. The firm’s president and chief executive, Kelly Shackelford, is a longtime friend of Paxton and has contributed $1,000 to a legal defense fund Paxton has used to fight an ongoing criminal indictment for securities fraud. First Liberty board member Tim Dunn is among Paxton’s biggest individual donors, having given him $820,000 since he first ran for attorney general. Political action committees associated with Dunn have also donated more than $950,000 combined to Paxton. Neither Shackelford nor Dunn responded to a request for comment.

First Liberty’s executive general counsel, Hiram Sasser, who briefly worked for the attorney general’s office under Paxton, said he doesn’t know how donations would have affected the attorney general’s decision.

But Sasser said he would have been disappointed had the attorney general chosen to represent the commission. He alleges that the commission is violating the Waco justice of the peace’s rights under the Texas Religious Freedom Restoration Act, which limits government actions that substantially burden someone’s ability to freely exercise their religion, and the Texas Constitution because it violates her freedom of speech and religion.

The judicial commission’s private attorneys said that the justice of the peace argued those points before the commission in 2019 but lost the case. They maintain that she did not appeal that case, so she has no right to pursue a new lawsuit that claims the warning was invalid.

State law says the attorney general’s office shall represent the judicial commission in court at its request, which indicates Paxton has minimal wiggle room to refuse to defend them, said Paul Nolette, director of the Les Aspin Center for Government at Marquette University, who researches attorneys general.

“This seems more like the AG choosing to adopt a certain constitutional interpretation and then saying, ‘Well, I believe it’s unconstitutional, therefore, I’m not going to defend it.’ But it’s still ambiguous. It’s not like an open and shut case.”

Contrasting legal approaches

While about 15 years apart, two cases against the University of Texas at Austin lay bare the different approaches taken by Paxton and Abbott, Paxton’s predecessor and now the state’s Republican governor.

Under Abbott’s leadership, the attorney general’s office defended UT-Austin in federal district court against a lawsuit filed by Abigail Fisher and another student. In the 2008 lawsuit, the students, who were white, alleged that the school’s consideration of race in admissions prevented them from being accepted. The attorney general’s office argued that the university’s admission policy was legal because Fisher had not proven it was adopted in bad faith. The office also argued the policy was narrowly tailored to achieve needed diversity there.

Fisher appealed the district court’s decision in favor of the university in 2009. Although Abbott did not represent the university throughout the entire appeals process, he submitted a nearly 50-page brief in December 2011 when the case first went before the Supreme Court, urging the high court to reject the case. The attorney general office’s leading argument was that Fisher, by then scheduled to graduate from another university in 2012, could no longer assert that she intended to apply to UT-Austin as a freshman or transfer student.

Abbott did not respond to a request for comment.

In 2016, the Supreme Court upheld UT’s affirmative action policies in a 4-3 decision. (Justice Elena Kagan did not take part in the decision and one seat was vacant at the time.)

In contrast, Paxton not only withheld a decision on representing the UT System in another affirmative action case earlier this year, but also kept the agency in limbo by holding off on allowing it to hire outside legal counsel.

On Jan. 12, a lawyer with the UT System sent a letter to the attorney general requesting representation after a man named George Stewart filed a federal lawsuit against six medical schools that had rejected his applications for admission. All but one of the schools were in the UT System. Stewart, who is white, argued that the schools were “unlawfully discriminating against whites, Asians, and men.” Stewart and his attorneys declined to comment.

Over the next several weeks, UT System attorneys contacted a deputy chief in Paxton’s office numerous times. They called. They emailed. The deputy chief told UT lawyers that “decisionmakers” at the attorney general’s office were aware that filing deadlines were approaching but were still considering the request, court documents show.

UT System lawyers eventually were forced to ask the plaintiff’s lawyer for an extension, delaying the case.

More than a month passed before the attorney general formally responded.

The attorney general’s office wrote in a letter that it agreed with the plaintiff’s argument that considering race and gender in student admissions was illegal and that it was awaiting the outcome of other affirmative action cases before the Supreme Court. The attorney general’s office also wrote in the letter that it had filed briefs urging the court to do away with affirmative action because it was “abhorrent to the Constitution.”

“For these reasons, we are choosing at this time to withhold a decision on your request for representation and for outside counsel,” the letter said.

UT could represent itself, the letter continued, but only for the purpose of requesting extensions in the case. Although state agencies like UT often have their own in-house general counsel, the attorney general is officially their lawyer. The state agency lawyers aren’t necessarily litigators, or litigation may only be a small part of their job. Often, their time is spent giving internal legal advice, reviewing contracts or consulting on employment issues. State agencies smaller than UT may not even have attorneys on staff.

Catherine Frazier, a UT System spokesperson, would not comment on the lawsuit or answer questions but said that the school, like every state agency, is required to ask the attorney general for representation or outside counsel. Every case is different, she said, and the UT System has ultimately been able to secure counsel.

Months later, the Supreme Court would rule in a 6-3 decision that consideration of race in college admissions violates the U.S. Constitution. But neither the attorney general nor UT lawyers knew how the high court would vote when Stewart filed his lawsuit.

“The law was clear that affirmative action was allowed (at the time),” said Terry Goddard, a Democrat who was Arizona’s attorney general from 2003 to 2011. “I don’t think you get to wait for the next round of Supreme Court decisions to make up your mind.”

Goddard’s approach to the attorney general role, he said, was that if he could make any constitutional argument in support of a law, whether or not he agreed with it, “it was your job to take that argument and do the best job you could.”

“Now, that’s not what we’re hearing today from people like Paxton,” Goddard said. “He’s basically saying, ‘Look, I’m not gonna make the argument at all.’ He didn’t even take what I think is the appropriate fallback, which is, ‘I won’t support it. And the record will show that I’m not supporting your position, but I’m going to get you counsel.'”

About a month after Paxton was impeached by the Texas House and suspended from his position, the attorney general’s office, while under the leadership of interim Attorney General John Scott, finally allowed the UT System to hire outside lawyers in the affirmative action case.

“Playing favoritism”

Just as Paxton has declined cases where he has an opposing view, he has chosen to get involved with others with whom he is aligned ideologically.

In 2020, Lucas Babin, a district attorney in East Texas, obtained an indictment against the streaming service Netflix for distributing the French film “Cuties,” a documentary about a Senegalese immigrant who joins a children’s dance troupe. The director has said the film critiques the sexualization of young girls, but critics focused on some of the film’s advertising depicting the girls dressed in tight, midriff-baring clothing or scenes showing them dancing. Babin alleged the film violated a state law that bans the “lewd exhibition of the genitals or pubic area of a clothed or partially clothed child,” which Netflix has disputed.

Less than two weeks before Babin announced the indictment, Paxton was one of four attorneys general who signed a letter to Netflix “vehemently” opposing the continued streaming of the film.

After an appellate court ruled in an unrelated case in 2021 that the lewd exhibition charge was unconstitutional, Netflix requested that Babin dismiss his indictment. Babin dropped that charge in March 2022 after he brought four new indictments that alleged the film violated state child pornography statutes.

On March 3, 2022, Netflix filed a request for injunction in federal court, arguing Babin was “abusing his office” by bringing the new indictments in response to Netflix’s effort to get the first indictment dismissed. The film had won awards, Netflix argued, and Babin was infringing on the company’s “constitutional rights.” (The Texas Tribune is among a group that has filed an amicus brief in support of Netflix in its case against Babin.)

The following day, Babin arrived in court, this time as a defendant, with a lawyer of his own: an assistant attorney general from Paxton’s office.

Under Texas state law, the attorney general is obligated to represent state district attorneys under limited circumstances, specifically when the case is in federal court and when the person filing the lawsuit is in prison.

It’s not unusual for a district attorney to ask the attorney general’s office for help, said Nolette. What’s surprising, he said, is that the state said yes.

“This isn’t a case where the DA said, ‘Please help me in this case to prosecute Netflix,’” Nolette said. “It’s that they’re being sued by Netflix for essentially prosecutorial misconduct. And yet, the AG is getting involved in a local issue where this is not a state agency.”

“It just gives the perception, and obviously some of this is specific to Paxton, that he’s playing favoritism,” Nolette said.

Neither Babin nor Netflix responded to a request for comment.

In November 2022, a federal judge granted Netflix’s request for a preliminary injunction, essentially preventing Babin and his office from pursuing new indictments against the tech company until the initial case is resolved. Babin has appealed that decision.

The attorney general’s office, along with a private attorney, continue to represent him.

Carla Astudillo of the Texas Tribune contributed reporting.