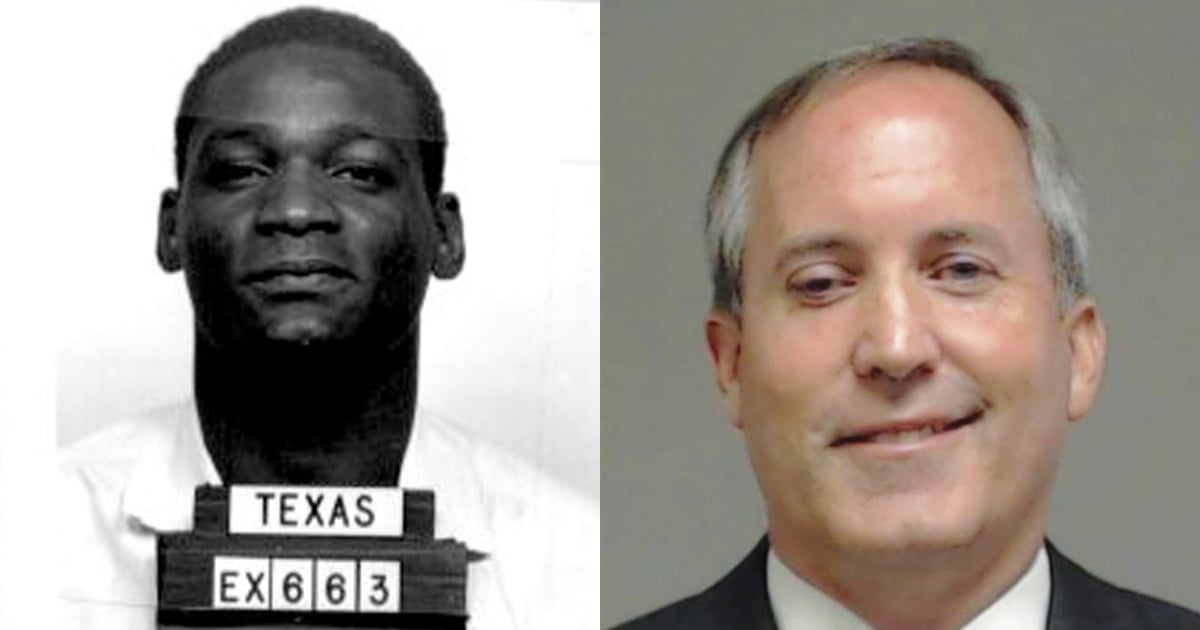

Ken Paxton’s Strange Quest to Execute an Intellectually Disabled Man

Prosecutors have agreed to spare Bobby Moore’s life due to his intellectual disability. Texas’ highest criminal court and top legal official want to kill him anyway.

As a teenager, Bobby Moore couldn’t tell time. Before dropping out of school in the ninth grade, he was so far behind his peers that teachers told him to draw pictures rather than try to keep up with reading and writing assignments. According to court filings, Moore repeatedly got sick from eating out of neighbors’ garbage cans in his Houston neighborhood, apparently unaware that the rotting food kept poisoning him.

For the past year, the Harris County DA’s Office has sided with appellate lawyers arguing that Moore, who was convicted in the 1980 murder of a Houston convenience store clerk, is too intellectually disabled to execute. Even as the death penalty loses momentum in Texas, it’s highly unusual for prosecutors to argue that a defendant’s life should be spared. But that hasn’t stopped Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton from fighting to have Moore executed.

In an extraordinary move last week, Paxton’s office filed a motion with the U.S. Supreme Court to intervene in Moore’s case, arguing to uphold his death sentence. Typically, the AG’s office only gets involved with death penalty cases if local prosecutors ask for assistance, and Texas law doesn’t authorize the office to contravene the decisions of local prosecutors.

In his filing to the Supreme Court, Paxton cautions against moving forward on the case “without the benefit of an adversarial presentation.” Since prosecutors won’t fight to uphold Moore’s death sentence, Paxton has asked the court for permission to “to file a true brief in opposition” to Moore’s claims. “The DA, who represents just one of Texas’s 254 counties, does not represent the Attorney General’s interest,” he wrote.

Paxton is virtually alone in his support for Moore’s execution. Numerous medical groups, legal organizations and prominent conservative lawyers, including former Baylor University president and Whitewater investigator Ken Starr, have filed amicus briefs urging the court to side with Moore.

Paxton’s office did not immediately return a request for comment on Wednesday, and Moore’s attorneys declined to comment.

Moore’s legal saga speaks to the recalcitrant way Texas, the epicenter of the American death penalty, has responded to the Supreme Court’s prohibition on executing intellectually disabled offenders. For years, Texas has executed inmates whom other death penalty states likely would have spared. That’s because the state relied on a legal standard rooted more deeply in stereotypes about intellectual disability than in medical consensus.

In 2002, the Supreme Court ruled that executing intellectually disabled people violated the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment, but it didn’t tell states how to determine who should be exempt. Most states turned to a combination of intelligence tests and clinical assessments. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (CCA), the state’s highest criminal court, instead established a slippery standard: the “level and degree of mental retardation at which a consensus of Texas citizens would agree that a person should be exempted from the death penalty.”

In 2004, the CCA made it possible for Texas inmates to meet clinical benchmarks for intellectual disability yet still not be disabled enough to avoid the death penalty. The ruling established a checklist for courts to weigh, the so-called Briseno factors, which went beyond clinical assessment and emphasized outdated stereotypes of intellectually disabled people. To illustrate the bar it wished to set, the court referenced John Steinbeck’s character Lennie from Of Mice and Men as an example of someone everyday Texans would exempt from the death penalty.

“What we’re seeing in Texas is not just extraordinarily rare, it’s essentially a rogue action, in contradiction of state law, in support of an outlier decision that every responsible organization agrees is wrong.”

Thus, Texas continued to put to death inmates who — to use a few real-world examples — couldn’t count money, got lost if they wandered a few blocks from home, or drooled during class. One study blamed the Briseno factors for the “strikingly low” success rate of Texas death row inmates challenging their executions on the grounds of intellectual disability.

That’s the legal situation that Moore confronted. In 2014, after a two-day evidentiary hearing, a trial court concluded that Moore should be spared the ultimate punishment due to his intellectual disability. However, applying the Briseno factors, the CCA overturned that ruling and blessed Moore’s execution the following year, putting his life in the Supreme Court’s hands.

In a 5-3 ruling, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg called Texas’ method for determining intellectual disability “an invention of the CCA untied to any acknowledged source.” Her majority opinion declared the Briseno factors invalid for creating “an unacceptable risk that persons with intellectual disability will be executed” and sent Moore’s case back to the CCA for re-evaluation.

Last year, in a filing with the CCA, Harris County DA Kim Ogg took the remarkable step of asking the court to reduce Moore’s sentence to life in prison and urged the court to conform to American Psychiatric Association standards for determining the intellectual disability of death row inmates. In June, the CCA upheld Moore’s death sentence anyway.

That puts the case back in front of the Supreme Court. In a filing with the high court last week, the American Bar Association argued that Texas has effectively resurrected the much-maligned Briseno factors “under the guise of a new standard for intellectual disability.”

Even prominent conservatives disagree with the way Texas has handled Moore’s case. In an amicus brief, a group of lawyers including Ken Starr argued that the CCA seems unconcerned with the rule of the law. The Texas court’s insistence on upholding Moore’s death sentence “reflects a disturbing disregard” for Supreme Court authority, the lawyers argued. The high court made it clear last year that “Moore is intellectually disabled and constitutionally ineligible for the death penalty.”

According to Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, it’s rare for a state attorney general to supplant local prosecutors in death penalty cases. He says it’s unprecedented for an AG to argue for killing a death row inmate whom local prosecutors have already agreed to spare.

“What we’re seeing in Texas is not just extraordinarily rare, it’s essentially a rogue action, in contradiction of state law, in support of an outlier decision that every responsible organization agrees is wrong,” Dunham said.